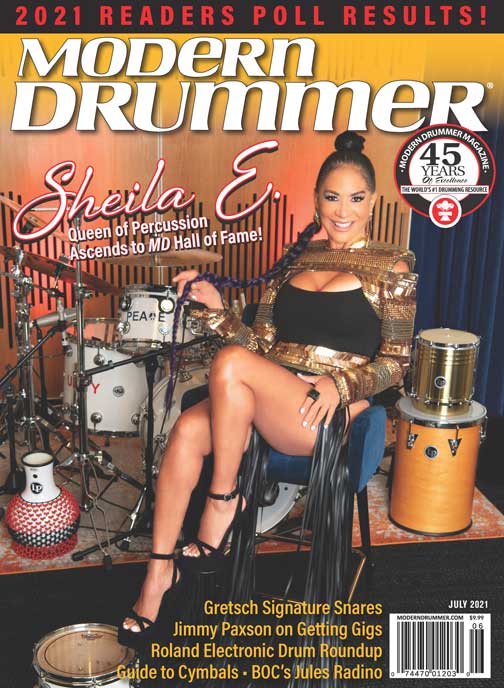

Sheila E.

Our Newest Hall of Fame Member Defines Purpose and Passion

Sheila Escovedo’s journey from growing up in a legendary family of percussionists, to seeing Karen Carpenter playing drums when she was just eight or nine, to performing with her dad Pete in Azteca when she was 15 years old, and ultimately transforming herself into Sheila E. “Queen of Percussion” is mostly the story of her deep love of performing, her diligent work ethic, and her uncanny ability to energize audiences.

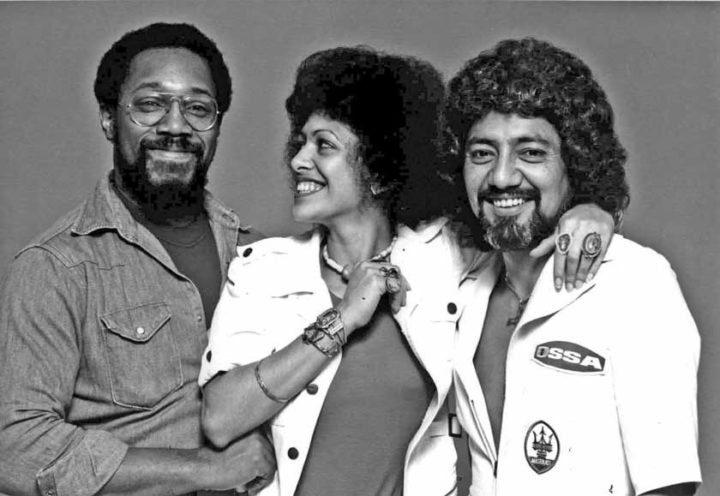

Playing with Billy Cobham—who produced two Pete & Sheila Escovedo albums (Solo Two in 1977 and Happy Together in 1978)—and joining George Duke’s band in 1977 elevated her profile. Tons of percussion credits followed—including being a part of Marvin Gaye’s final tour in 1983—until her musical and close personal relationship with Prince launched a hitmaking solo career and international celebrity.

Her 1984 debut album, Sheila E. in the Glamorous Life, produced a top-ten smash on the Billboard charts (“The Glamorous Life”), which was followed in 1985 by the hit “A Love Bizarre” (from her second solo album, Romance 1600). She contributed to Prince’s masterful Sign o’ the Times in 1987, as well as the resulting tour—her first playing a drum set for an entire show—and the two collaborated on and off and remained friends until Prince’s death in 2016. Advertisement

In 1998, she became the first woman to become a bandleader on late-night television when she fronted Magic Johnson’s house band for The Magic Hour. She logged three tours with Ringo Starr’s All-Starr Band (2001, 2003, and 2006), and the Beatle returned the favor by playing on her version of “Come Together” for her 2017 album of inspirational songs, Iconic: Message 4 America.

Sheila first appeared in Modern Drummer in the December 1982 issue, and first graced our cover for the July 1991 issue. In 2005, she performed at the Modern Drummer Festival with the Latin All-Stars, featuring Alex Acuña and Santana’s percussionists Raul Rekow and Karl Perazzo.

That was a big deal,” she says. “My tech built this special drum set and frame to make it look different. I wore all white, and we didn’t rehearse anything. We talked backstage about what we were going to do, and then we walked on stage and played.” Advertisement

The whirlwind of activity never seems to stop for Sheila. Even putting aside her onslaught of sessions for artists such as Gary Clark Jr. (2019’s This Land), her productivity is remarkable. She released her autobiography, The Beat of My Own Drum: A Memoir, in 2014, and worked with renowned film composer Hans Zimmer on several soundtracks. She has led musical tributes to Prince for the Grammys and BET Awards, starred on an episode of Fred Armisen: Standup for Drummers on Netflix, and created Sheila E. Teaches Drumming and Percussion for MasterClass. As if her musical pursuits weren’t enough, she recently developed three Sheila E. collections of scented candles—Glamorous Life, Love Bizarre, and Erotic—with business partners Kinley and Tricia that are available through sheilae.com.

Onstage, it’s astounding to watch Sheila in action. She can lay down a smooth groove or tear it up with blazing chops—while singing and/or dancing. It has been a long-time coming, but Modern Drummer is gratified and delighted that she is the first woman inducted into our Readers Poll Hall of Fame. All hail the Queen of Percussion!

Congratulations! You’ve won so many prestigious awards, of course, but how does it feel that our readers voted you into the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame?

Wow! I am humbled. I’m trying not to cry. I’m so emotional. It’s hard to believe it has taken this long for a woman even to be nominated in this category. There are so many incredible drummers all over the world, and some of them happen to be women. There are more women playing now than I have ever seen in my entire life. For me to be the first—wow—I am so grateful. Thank you to all the people who voted for me. Advertisement

You grew up in a musical family. How did that support inform your career?

I was very fortunate to grow up in a home that was constantly filled with music. The advice from both my parents was always, “Whatever you want to do, give it your all. Give it 150 percent. It’s not going to be easy. You’re going to have to fight for it, and really believe you can do it. There will be a lot of no’s.”

And I’ve had—and I still get—plenty of no’s. And that’s okay, because there are certain situations that maybe aren’t supposed to happen yet. You might not be ready. But some of the no’s for me turned into opportunities. A “no” doesn’t mean you aren’t qualified. Perhaps it’s simply not right at this time. Maybe it’s not this door, but another door will lead to something else that might have been better for you than the one you really wanted. So, take that “no” as a blessing, because it took you somewhere else. My parents used to tell me, “Just keep moving forward, figure out what your passion is, and then go for it. That passion becomes your purpose.” That advice was so important. Once I knew that I had to play drums and percussion, my whole life opened up.

Besides your dad, who else inspired you?

Almost everyone I watched play music. My brothers and I would go see local bands and famous people. It didn’t matter—we just wanted to hear music. We would go to the side of the stage, and ask, “Can we sit in?” And they’d be like, “No. Get out of here!” [Laughs.] Then, we’d go to another show, ask to sit in, and get a ‘no.’ We just kept begging. Even though those no’s were no’s, we’d watch and become a part of that family of musicians. This really changed my life. Advertisement

What was your first professional musical experience?

At 15 years old, I went out with my dad’s band, Azteca. That’s when I really knew this is what I wanted to do. Within two weeks of playing with my father’s band, we went to Bogotá, Colombia. It was the first time I was ever on a plane, and the first time I had left the country. That first tour with pops was my first musical experience.

How long after that experience did you tour with George Duke?

It wasn’t very long. I was still fairly young. I met George through Billy Cobham, who had come to see my father’s band while I was playing with him. Billy said, “I’d love to produce you and your dad.” We didn’t know whether to believe him. He came back a few months later, when he was out with George Duke, and we did do our first record with Billy. I was probably around 16 or 17. We did two albums with Billy. I met George Duke around 1976, and I went on tour with him.

Were you playing percussion or drums with George?

Percussion. Ndugu Chancler was playing drums. But, as part of the show, Ndugu would go up front and play Rototoms for one song, which George had called “Reach for It.” He would say to me, “E—why don’t you play drums?” So, that was the first time playing drums in a band. It was a bit hard, because Ndugu’s ride cymbal was way up in the air. It hurt to play on that kit. So, I stayed on the hi-hat and played in the pocket. That was my job. Advertisement

I learned a lot being in George’s band, because he allowed us to grow as musicians. He always said he would never tell us what to play. He’d say, “You just do what you do, and if there’s something I can add, I’ll suggest it.”

You started learning percussion by mirroring your dad.

Yes. My dad and I are right-handed, so we would sit across from each other. I’d look at his right hand, and I’d do what he did with my left hand. I was mimicking him in a mirror image. When I would sit on his congas, they were set up right-handed, of course, but I didn’t realize I should have switched them around in order to play what I heard. I didn’t realize I was playing left-handed.

Perhaps that’s one of the factors that gave you your own style and sound. When did you switch over to drums?

I really noticed the drums when we were working with Billy Cobham. I was amazed by his setup because it was not typical. He did not position his toms in size order—10”, 12”, 14”, and so on—they were all over the place. He also had two bass drums, and he played left-handed. Watching the way he played with his double kicks and hearing the sounds of his snare and toms was incredible. Advertisement

“I learned a lot being in George Duke’s band, because he allowed us to grow as musicians. He would never tell us what to play.”

One thing he would do as a warmup was to stand with his elbows to the wall and do rolls. His hands would move up and down, but his elbows would never move at all, and the sound would stay the same. It never varied. I’ve never seen anything like it.

One time, I asked if I could play his drums. When he played, it sounded amazing. It did not sound like that when I played them [laughs]. His sticks were so big and heavy. Watching him play was incredible. What a great class to be in. So, I got into drums because of Billy Cobham. How could you not be inspired?

Were there any tips you and your dad picked up from Cobham about percussion?

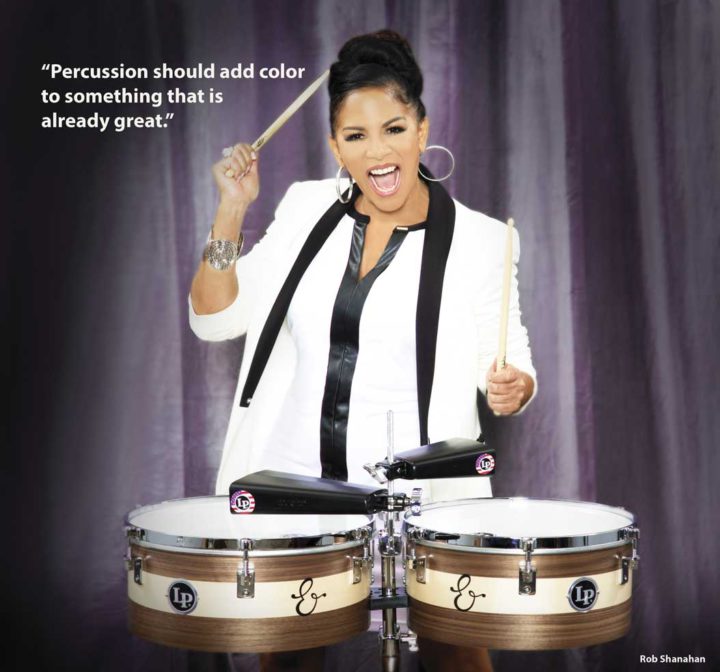

Billy plays a lot, so he was teaching us when not to play. You’d have to find pockets and spaces where things didn’t sound cluttered. You want it to sound like music and movement, so the three of us had to perform like one unit. For example, if Billy was getting ready to do a roll, you’d have to play after his roll—even if you really wanted to do a roll yourself. As a percussion player, that’s a general rule—do not get in the way. Percussion should add color to something that is already great. Advertisement

When did you first meet Prince?

Prince saw me play drums with George Duke on that song, “Reach for It,” on Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert or The Midnight Special. At that time in the 1970s, those shows were not only one genre of music. Everyone played those shows—from Sly Stone to James Brown to Creedence Clearwater Revival and all the rock bands. I think Prince’s first album had just come out when I went to see him perform in the San Francisco Bay Area. I went backstage to introduce myself, and he said, “I already know who you are. I have been following your career.” He told me that he saw me on those music shows, because he wanted to play them.

How many years did you tour with Prince?

I never really think about how many years it was because it was sporadic. We first started working together in 1983. Then, it was on and off through the years. I left after Lovesexy [1988] because I wanted to do my own record, Sex Cymbal [1991]. I also wanted to play with other artists. I left for about a year. but I was still living in Minneapolis, and I continued to work with him when I could. I was always there—in and out.

“Prince knew what he wanted, and it was nice whenever we were able to bring things to the table.”

Let’s talk about Sign o’ the Times.

The album Sign o’ the Times [1987] also had Bobby Z and Prince on drums—although I played drums on tour. That was the first time I was the drummer for an entire show. We only switched for one song, “It’s Gonna Be a Beautiful Night.” I had told Prince I wanted to play drums with someone, and he said, “I’m going to change up my whole band, so let’s start a band together.” That became Sign o’ the Times. I brought a couple of musicians from my band, and he kept a couple of his players, but it was still his band. Advertisement

You deserve a lot of credit for that period, because when people think of Sign o’ the Times, they think of you and Prince together.

Thank you, but, yes and no. It’s all him. It’s his music and his ideas. He knew what he wanted, and it was nice we were able to bring things to the table, as well. Sometimes, a song would even turn out a little different than what he would think. That environment was about having people around you who could change genres, vibes, and even throw in some Mile Davis or Charlie Parker. Recording and jamming was really cool.

When you were in the studio with Prince, did you discuss who was going to play drums on a track?

No one ever discussed who was going to do what. If he said, “Show up at the studio at 3 AM,” you just did. The drums are always set up. If he was on the drums, I would go to percussion. If he was on the bass or guitar, I’d sit on the drums. If he did specify that he wanted me to play percussion only, then John Blackwell would be on drums. But, basically, Prince would just count off a song, and we’d all start playing.

How did your experience with the Ringo Starr All-Starr Band come about?

My manager at the time said, “You are going to be shocked to find out who called you to do something.” She started to say his name, and I said, “Yes—whatever he is asking. Yes!” I didn’t even let her finish the sentence. What an unexpected blessing to be able to play with Ringo. I couldn’t even believe it when I met him. He started talking to me, and I didn’t even know what to say. I’m thinking, “I’m talking to Ringo Starr. A Beatle!” He is a remarkable and sweet man. Advertisement

What did you learn from him?

He is such an incredible drummer. In order to understand his way of playing, I had to break it down and figure it out, because we were going to be two drummers playing together. To get an idea of his rhythmic sense, I even studied how he walks. I always tell everyone to practice, practice, practice, but I don’t [laughs]. But this was one of the few times in my life that I really practiced, because I was going to learn how to play like Ringo. Everyone knows the Beatles’ songs, but now I had to really play them. I wanted to make sure the fills were in the right places, and whether he played hi-hat or ride on some parts. What astonished me most was, I’d be playing with my eyes closed, and I would get ready to do a fill, but Ringo had already started the fill. What? The fill was in time, and he wasn’t rushing, but where I would normally play the fill, he would be half done. I finally figured out that he starts a fill with his left hand—not his right—so he’s already underneath the part and into the fill. That was a trip for me. It was like opening a door. I get it now, but I had to change the way I played.

What was it like recording the Beatles’ “Come Together” with Ringo on your Iconic: Message 4 America album?

I told him, “It’s your song—you should be playing on it.” He left me a message saying, “Of course.” Initially, the idea was that I would play drums on the song, and then we’d both take solos. He wasn’t in town when I recorded the song live with my band, and I thought it would be cool for me to do the classic tom intro on congas. Afterwards, he told me, “I’m glad you did that, because I was not going to play that intro. I played it the one and only time on Abbey Road, and that’s it.”

I had him play through the track at his studio, but he never heard the arrangement at all. He only wanted to hear the tempo, and then he said, “Let’s go.” We did a long version of the song, and about four minutes in, he looks at me and says, “This song is long!” [Laughs.] I kept everything he played, and everything fit perfectly. At the end, he said, “Are you kidding me? The song is still going.” [Laughs.] He is amazing! Advertisement

When I read your 2014 book, The Beat of My Own Drum: A Memoir, it was clear the hardships of the music business were difficult lessons for you. Like when you were doing all those elaborate MTV videos, and you realized you were paying for everything.

Yes. It was a huge lesson to learn. I was on tour for more than a year, and I came home $900,000 in debt. I’m thinking, “How did that happen?” Well, any time I asked management for something, it was always, “We got it. We’ll take care of it.” I thought they were going to take care of it. I didn’t know I had to pay for it all. My advice is to always read the small print.

So many artists don’t understand the business deals, and they end up with little or no money.

Being in the music industry—especially now because things have changed so much—you have to make sure you know what you are doing, and what you are responsible for, business wise. If you don’t know, you have to ask questions until you really understand what it means—and then continue to ask questions. Don’t be ashamed or feel bad. Don’t sign anything until you understand everything. I wish I had taken a business course in school, but I left so early. As a result, I learned the hard way. I’m still learning. Advertisement

“We did a long version of ‘Come Together’ that I got Ringo to play on. About four minutes in, he said, ‘This song is long!’”

Many musicians are happy just to play, and sometimes people take advantage of that passion.

Yes! I used to feel somewhat offended being paid for something I really loved to do. At the beginning, I was like, “Please, keep your money.” But then pops pulled me aside, and said, “Do you see the refrigerator? We need some food.” [Laughs.] He said it was okay to make deals and get paid. But it was still a process for me. Do I accept what someone offers? Do I negotiate?

I’ve been enjoying your internet TV show. I dug the one with Fred Armisen—who was on our April 2021 cover.

Fred is a great friend, and I think he is a really good drummer, but he doesn’t think he is that good. When he did my show, I was going to surprise him, because I wasn’t going to tell him my dad was going to be there. Fred loves my dad and his music. But I had to tell him, because it was filmed during COVID, and we all had to get tested. He was so excited and impressed. The only thing I didn’t tell him was we were going to jam at the end. I brought out all these LP congas and a percussion box, and we just jammed. He loved it. He also wanted to show pops he had his album on cassette. Fred was like, “You can’t have this. I just wanted to show you.” [Laughs.] Advertisement

In his MD feature, Fred talked about your appearance in his Netflix comedy show, Standup For Drummers.

The filming of that show was actually the first time I met him. We had a great time. He said, “Let’s just improvise,” and we kind of went off script. He had about eight bass-drum pedals in a circle connected together. I did some improv stuff, and he’d say let’s try this or let’s try that. I loved working with him. I am such a big fan.

What drums have you been using these days?

When I recorded Iconic: Message 4 America, I used my new DW custom kit. Bringing people together was the focus of the album, so it has “peace, love, and unity” written on the drums, as well as graphics of hearts. I also asked LP to make white congas and bongos with the same design. I wanted everything to vibe with the feel of the album. As Ringo would say, it’s about “peace and love.”

You must get a ton of endorsement offers, but you tend to stay with just a few companies.

I’m always getting a lot of offers, but I only endorse what I believe in. I’ve only been with two drum and two cymbal companies my entire career. If I like something, I’m going to stay there.

Interesting story—I found a letter in my scrapbook I had written to Yamaha when I was nine years old. I didn’t even realize I wanted to be a drummer until I saw Karen Carpenter play when I was about the same age. So, I asked Yamaha to give me some drums [laughs]. But, moving forward a few years, the first endorsement I had was with Yamaha. I still have those kits, and I love them. I switched over to DW, and I’ve stayed with them. I started with Paiste cymbals, and I’m currently with Zildjian. Then, I used LP gear at first, switched to Toca, and now I’m back with LP. Advertisement

Are there any more words of wisdom you’d like to share with MD readers?

First, I want to thank the readers again for voting me into the MD Hall of Fame. I also want to say that I know artists can sometimes feel like there’s nothing else they can do, or they become frustrated and want to stop playing. I’ve had a bucket list for 30 years, and I’m still checking things off. I was on the cover of MD once before, and now I’m on another cover and I’m in the Hall of Fame. So, my advice is to never give up. You never know what’s going to happen.