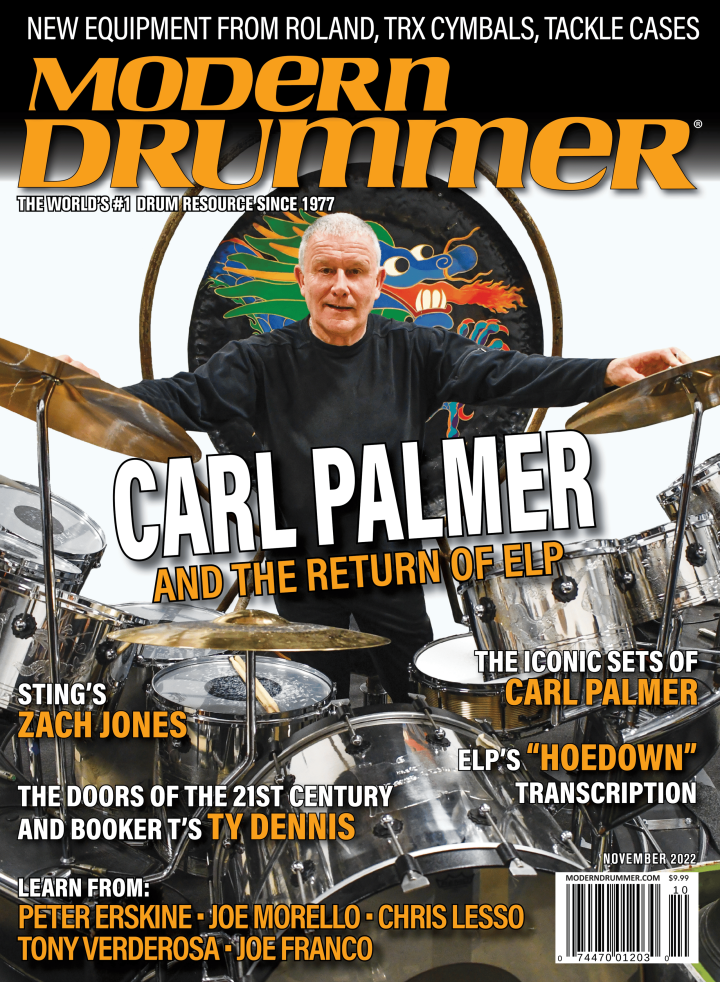

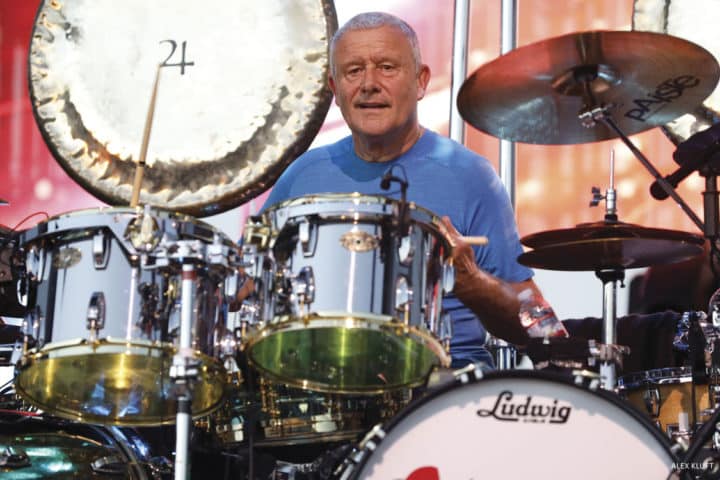

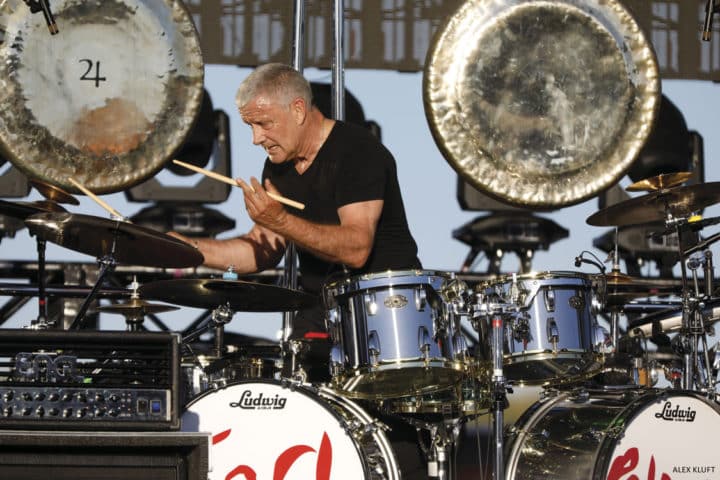

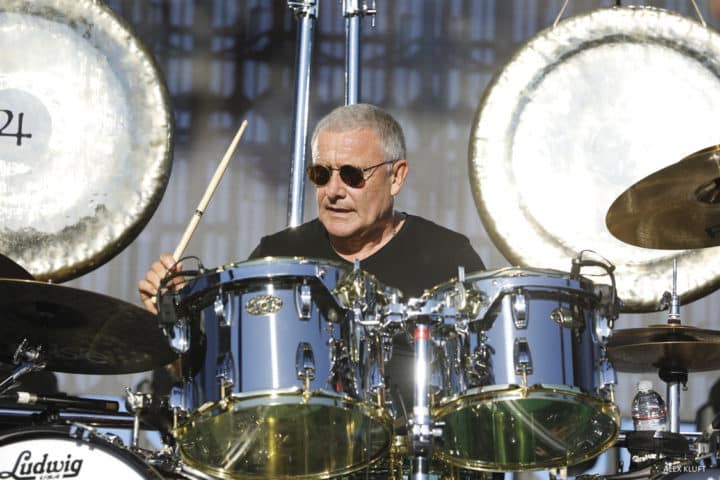

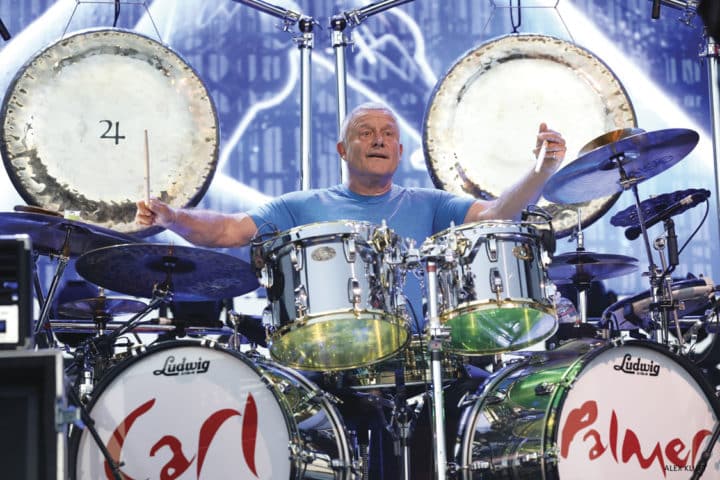

Carl Palmer: Welcome Back My Friends…

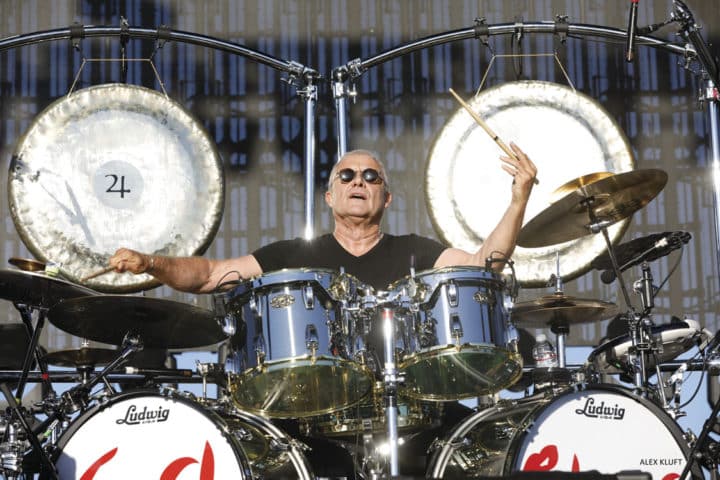

Carl Palmer is a drumming legend. Name another drummer who had #1 hits with four different bands? His drumming in Emerson, Lake, & Palmer is epic and renowned. His drum parts and playing in the band Asia are unforgettable. His larger-than-life drumsets are etched in drummer’s minds around the world. He is one of the drummers that lit the torch for virtuostic and long drum solos in rock music, and he is still carrying that torch today.

This month, Carl will continue the tradition of playing the big rock and roll hi tech stage productions that ELP began in the early 70s. His new Welcome Back My Friends, The Return of Emerson, Lake, & Palmer Tour is going to amaze and inspire a new generation of musicians and ELP fans. But this tour does raise some questions, and Carl isn’t hiding from them. Both Keith Emerson and Greg Lake were musical icons who died in 2016. So how can this be The Return of Emerson, Lake, & Palmer? Listen to Carl’s honest explanations about this new tour, his musical intentions, and the long process of putting this tour together. We also explore his drumming and musical background, the misconceptions of ELP, the new Emerson, Lake, & Palmer Singles box set, the differences between English and American drumming, and the many lessons that he can share from 50 plus years as a professional musician.

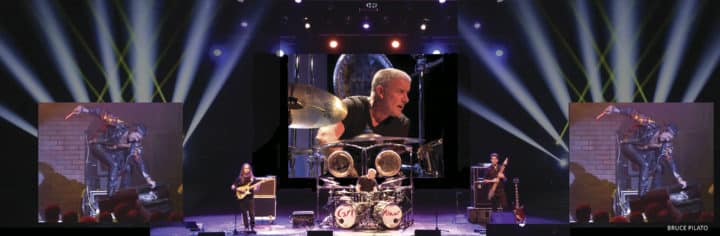

MD: This new tour is looking to be a big production, which is really nothing new for you. ELP was one of the first bands to bring a big spectacle of a show to the stage with a rock and roll concert. Can you explain what we will be seeing on your new tour? Advertisement

CP: I will have three screens on stage, and both Keith Emerson and Greg Lake will be seen playing their parts on these screens during the show. I am playing live with audio tracks from one of our shows that was filmed at Royal Albert Hall in 1992. It was one of our best shows. When we did that five-camera shoot, the audio was all recorded on a multitrack and everyone was on individual tracks, so it was possible for me to have absolute control over the audio, and I can play with Greg and Keith as we played together live. The audio is superlative, and the video is very good. The video is not “Imax” quality, but I think it all really works well.

MD: It sounds like that big process could present some production issues, have there been any speed bumps along the way?

CP: Not yet. I am not playing the entire show from the Royal Albert Hall footage. I have my band as well. I am playing “Hoe Down” “Carmina Burana,” and “Tarkus” with my band, so between the songs with Greg and Keith, and the songs with my band, we have a nice presentation and flow going on for the live show.

This is the only way to play ELP music with Greg and Keith in any way shape or form. I did look into the hologram routine, but to tell you the truth, it’s a bit too spooky for me. If the tables were turned and I was no longer here and they were, I would want them to get the best live performance that I had ever done, and to do what I am doing with the screens and the live footage, not a weird looking hologram. Advertisement

This Royal Albert Hall performance came from two sold-out nights. I was so happy to come across this footage. There were six tunes that I could incorporate into the set using Greg and Keith’s actual performances when they were playing at their very best, and (as I said) the audio is spectacular. For me, this is the most honest and the best way to present our music today, I know they both would approve, and the Lake and Emerson families are both totally behind this project. If they were unhappy in anyway, with anything about this project, I wouldn’t have gone ahead with it. I know that both Keith and Greg would have been up for doing something like this, as a band we were always trying something new, so now I am going to give it a try.

MD: But the new show is not only you and the footage, you also have your band with you, who is in your band now?

CP: Paul Bielatowicz has been my guitarist for 18 years, and Simon Fitzpatrick is playing bass and Chapman stick. They both sound fantastic, Simon and Paul are triggering a lot of synth sounds. I was never trying to put together another ELP. That has never been my intention. Sure, I could have gotten some Keith Emerson clone to play his parts but that’s really not what I’m about.

MD: And that would be a “good imitation” at best.

CP: Exactly, and I am not into good imitations. I am really trying to show how versatile the ELP music is. In the past, ELP music has been played by orchestras, string quartets, jazz groups, and in just about every way imaginable. Since the ELP music has already been played in many shapes and forms, I have chosen to play it with a guitarist and a bassist (who also plays the Chapman Stick.) Advertisement

I understand if the loyal ELP fans don’t like my new take on the music, I get that. This is just a new door that I wanted to open, and I think it sounds fantastic! I understand if you are a keyboardist or a synthesizer freak, and you have spent lots of money on seeing ELP concerts in the past. You love the band, and so do I. ELP was keyboard driven, for most of the time there wasn’t a guitar in sight. We were weird in that way. Now the ELP drummer puts together a band with a guitarist instead of a keyboardist. I get that some people might not like that. But I started this band in 2001, I didn’t bring it to America until 2007, and we have had a great time experimenting with the music.

MD: Some people have very strange opinions on recordings and music. They always want to hear things played exactly the same as it is in their memory or on the records. But they don’t realize that songs are living breathing things that evolve, mature and change, sometimes for the better, sometimes not. But as musicians, we have to let the songs do that and see where the music wants to go. 50 Years ago, I’m sure people weren’t very happy when some rock band called ELP started playing and interpreting legendary classical compositions either.

CP: Like classical music, I think ELP music is rich for interpretation. At the beginning they called us “Prog Rock” which (in my opinion) is such a cheap title to give our music. We were (and are) playing eclectic music that had elements of jazz, classical adaptations, folk, and rock and roll. However, many people forget that we created many wonderful ballads too. Why would you call ELP prog rock when our biggest singles were “Lucky Man,” “From the Beginning,” “Still… You Turn Me On,” “Footprints in the Snow, and “C’est La Vie?” Music is for enjoying, not for labeling and putting into a time capsule. Advertisement

MD: Are there points during the show where your band with Paul and Simon and yourself, and Keith and Greg are all playing together?

CP: Absolutely. In “Welcome Back My Friends…” the footage and the video was wonderful up to a certain point. So what we are doing is after the first keyboard solo we morph right into me and my band playing live.

Obviously, if Keith, Greg, and I are playing “Knife Edge” or “Lucky Man” I don’t need my band playing. However, if I can improve things by having Paul and Simon double some parts, I have them do exactly that.

If this whole tour goes well, I won’t be the only one doing this, I think it’s all coming together very well. Of course, the whole show has a bit of trial and error to it, but we’re getting it right, and that risk is what makes it fun and new. Advertisement

MD: Everything that we do in music is trial and error, in my musical life I often lean on something that Tony Williams told me, which was, “I don’t trust musicians who don’t make mistakes, they are just not trying hard enough.”

CP: That’s exactly it. I like to live a little dangerously. Some drummers can “just play the chart,” but that’s not me. I like to get a bit of candy in there as well. It might not always be as sweet as it should be, and sometimes it might be slightly sour, but I’m always going to go for it.

You need to take risks to improve, I don’t think that you can just continue to polish things over, you have to keep trying new things. I’m 72 years old, it’s really important for me to take chances and try to improve. I want to go as far as I can. If I don’t wake up tomorrow morning, at least I will know that I tried. I am going to stay at the top of my game for as long as I can. At the end of the day, it’s not about how many drum clinics that you can do. For me it’s about what music you create, what you can give back, and what personal standards that you have held yourself up to. This new tour is really my way of presenting the ELP music that I love, in the classiest and most hi tech way possible. Advertisement

MD: This is really nothing new for you. ELP was one of the first bands to bring a big visual show to the rock stage, wasn’t it?

CP: That’s kind of true. I start the new show with an older video clip shot from above our three tractor trailers that we took on tour to carry all of the equipment. ELP was referred to as a “saber rattling group” we were really trying to do something new and different. We were just experimenting our socks off and being exceptionally “English.” However, whatever we did was done to enhance the music. If something didn’t work with the music, we wouldn’t do it.

I met Keith when I was 17 and I was playing in London with Fleetwood Mac because Micky Fleetwood was ill. That night Keith was playing in The Nice (with Brian Davison on drums and Lee Jackson on bass.) I had seen them before, but that night I watched them from side stage, and their presentation was so exciting. Keith was riding his L100 Organ across the stage and stabbing the organ with a dagger. When we finally got together, I told him that he had to keep doing that entire presentation, and we figured that I should have to do something too. I started with the gongs and the revolving riser, and Greg had his huge $10,000 Persian carpet that he stood on. That’s where it started, and it just grew from there. The evolution of our presentation was part of each of our individual DNA.

Pink Floyd always had a bigger show than we did, they were doing some serious stuff on stage. The English band Hawkwind was doing interesting things on stage too. David Bowie was doing the makeup thing before us. But yes, we were one of the first bands to create a big production of a rock show. I can see what you are saying about this tour as a continuation of that type of thing and this show being really nothing new for me. But I must say that what ELP were doing was nothing compared to what the Rolling Stones or U2 is doing today. Advertisement

MD: Sure, but ELP opened that big door that other bands have since walked through. Now you are just walking through that same door that ELP first opened in the 70s.

CP: It actually began before ELP. In 1968, the first band that I was ever in was called The Crazy World of Arthur Brown. We had a hit single called “Fire.” Arthur used to come out with a head dress that was on fire and introduce himself by saying, “I am the god of hell fire, and I bring you fire!” That was the beginning of psychedelia. He wore makeup, we all wore masks on stage. This was long before KISS. In 1968 that song was a #1 hit in America and England, and on the charts all throughout Europe. I picked up a lot from the experience of playing in that band. When ELP first got together, I didn’t say let’s paint our faces and wear masks, but I did say why don’t we do as much visually as we are sonically. We did the quadraphonic thing live, but I thought that we should add to that with some visuals.

In the 60s and 70s you played concerts to promote your album, you didn’t play concerts to make money. You played concerts to take the profits from the concerts and re-invest into future concerts to make them better. That is how you would attract more fans and sell more albums and make money. Obviously, the times and the business have completely changed today, but that’s how it used to be. The unfortunate thing is that by the time the big arena tours had really taken off, ELP had broken up. We never really got a chance to do a big arena tour. We did lots of big concerts in front of 100,000 or more people, but we never really got a chance to do a continuous big arena tour. I don’t want to sound like I am complaining because I’m NOT! I have had an incredibly blessed life and career.

I have been in four different bands that had #1 hit singles, and I didn’t even write any of the songs. I don’t know many musicians that can say that. But I played on Arthur Brown’s “I Am the God of Hell Fire,” Atomic Rooster’s “Tomorrow Night,” ELP had many hit singles, and a few #1 singles, and of course Asia’s “Heat of the Moment” went to #1. I’m not the wealthiest man in the world but I’m doing just fine. I am just continuing to do what I do, because I have been so incredibly lucky to be able to do that for my entire life. Advertisement

MD: In the notes to the new Emerson, Lake & Palmer Singles box set you say, “This box set of singles is very important to the development of ELP. The music that you will hear opened the door to radio around the world, and then the musical concept of ELP was born.” What do you mean by that?

CP: As I said, to call ELP a prog band was really under-playing us. We were a big singles band. We had a lot of three chord ballads, and lullaby type ballads. Those songs were NOT prog rock. I came up with the idea for a box set of the singles. These were the tracks that opened up the airwaves for Emerson, Lake, & Palmer to record things like Brain Salad Surgery, Pictures at an Exhibition, and Tarkus. To get those records played we had to have songs like “Lucky Man” “From the Beginning” and “Fanfare for the Common Man.” Those are the tracks that made us radio friendly. No one was going to play 14 minutes of “Pictures at an Exhibition” by Mussorsky, but they would play “Still… You Turn Me On.” We even had a radio hit single in Germany playing the theme from “Peter Gunn” by Henry Mancini. The singles in this new box set are the most important tracks in the history of the band. Then we got the original bags that the 45s originally came in and reprinted them.

Everyone knows about the long songs and the solos, but the singles are an important part of the story of Emerson, Lake, & Palmer. But in order to get the complex music across, we had to wrap it up in something. And those simple songs and ballads did just that. The last great single we had was off of the Black Moon album, and I am doing it on this tour, it’s called “Paper Blood.” Advertisement

ELP had a very eclectic makeup. Greg Lake was big into Simon and Garfunkel and The Beatles, and Greg could write beautiful simple tunes. Then we had Keith who was about classical adaptations, he wanted to take classical music and make it our own. Musically, I could meet with both of them, I loved the Beatles, jazz, and classical music.

MD: What type of classical music were you listening to at the time?

CP: Keith and I were into Shostakovich’s “Symphony No. 5,” Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” Bartok’s “Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion.” I even liked the lighter stuff like the Elizabethan Waltz’s by Mantovani.

My grandfather was a serious classical musician, his brother was a classical percussionist. They wanted me to become part of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. That was a “proper job.” At the same time my dad was a huge jazz buff and he played jazz around the house all of the time. He was getting me into Duke Ellington, Errol Garner, Oscar Peterson, Modern Jazz Quartet, and I was loving that music. Then I heard Elvis Presley “Jailhouse Rock,” and my dad took me to see The Gene Krupa Story. That was IT! I was all in. I learned how to play the drum set which caused some havoc in my family, but I kept learning about classical music. In fact, when ELP was at its peak, I was attending music school to learn classical percussion. I even got to play a few nights with the London Symphony Orchestra. I played the tricky cymbal part during “Romeo and Juliet.” Hearing all of that great music was a wonderful way to grow up. I learned more than I had to, which was wonderful. Advertisement

MD: “Learning more than you had to!” There’s an important lesson right there.

CP: But it benefitted me. Later on, when ELP was playing “Pictures at Exhibition” I went and bought the mini score so I could add the tympani parts and the bell parts in the appropriate places.

I think it’s important to become familiar with as much music as possible. You need to understand what is going on in all of the areas of the music that you are playing. You also have to find out what you “do well” in music. And you’ll never find that out, if you know nothing about it. You might grow into or develop whatever that is.

MD: You’ll never know if you are a good songwriter unless you try writing a few songs, right?

CP: Absolutely.

MD: I am fascinated by the tradition of English drumming, although I have to say that most of the time you sound more American than British. A little while ago you mentioned that ELP was, “Just being English.” What does that mean, and how does it relate to drumming?

CP: Everything that I play I have stolen from an American drummer that’s for sure.

MD: But there is something that makes British musicians different? What is it?

CP: Everyone has to be influenced by someone or something, whatever that might be. In music you need to go to the best source of musicians to be influenced. Those “best musicians” can come from any approach: jazz, classical, big band, rock, whatever. In America you have more of everything, including musicians. I looked to America for musical influence. In England we do have had some great musicians: Kenny Clare, Jack Parnell, Ronnie Verril, Ronnie Stephenson. There is an awful lot that I could pick up from those British musicians. But for some reason, there was a slightly higher musical standard in America. Advertisement

MD: But I think there’s more to it than that.

CP: There is. Today, you can become a Dave Weckl or Vinnie Colaiuta clone, and many people do that really well. In England, we have all of the same information available to us that everyone else has to do that. But the English musicians that I know are better at disguising where we have stolen things from. I have found that individuality seems to be very important to British musicians. We go in through the front door (like everyone else,) but then we sneak out through the back door and try to disguise what we have stolen. Both American and British musicians have high standards, but we Brits don’t do cloning as well as the Americans. I don’t know if it’s because we can’t, we don’t want to, or that we are more aware of it. But we don’t hero worship as much as American musicians.

My drum influences have been very simple. When I went and saw Gene Krupa play “Drum Crazy” in The Gene Krupa Story that was it. Then I heard Time Out by Dave Brubeck. Then I heard Buddy Rich Sings Johnny Mercer, but he wasn’t playing much drums. Then I heard Buddy Rich plays Count Basie (actually called This One’s for Basie) and a huge door flew open. For me it was about gathering the material and influences, and I think we Brits are a little better at the gathering process.

But I’ll tell you honestly that I keep a list of younger drummers here in my office, I like to keep track of what they are doing and there are some great young drummers that I have heard recently. There are almost too many to keep track. I still try to steal whatever I can from these younger guys. Advertisement

MD: Who are they?

CP: Willie Jones III, Eric Moore, Chris Coleman, Daru Jones, Aric Improta, the list goes on and on. There is a lot to be influenced by in American drumming.

MD: But there are American drummers who are just discovering some older British drummers like Michael Giles, Steve Jansen, Clive Thacker, and Jon Hiseman. So the lineage or the continuum goes both ways, backwards and forwards at the same time.

CP: Michael Giles was always a fantastic player. Greg Lake used to always tell me to listen to Michael Giles. But when I heard the sound of his taped-up drums that were deadened and flat sounding, I knew that I couldn’t play like him. I had my drums tuned like a big band drummer and my dynamics aren’t the greatest. He played perfectly for how his drums sounded, but I knew that I couldn’t play what I played on drums that sounded like that, it just wouldn’t work. But he sounded so original. He was the first drummer that I had heard playing double bass drums on fills on King Crimson’s “In The Court of the Crimson King.” You also mentioned Jon Hiseman, he was a phenomenal player as well.

MD: Can I ask you about your upbringing?

CP: I come from a place in the North called the Midlands, Johnny Bonham and I came from the same town. There were a lot of musicians in my family. As I said, my grandfather was a conductor, his brother was a professional drummer. My step-father was a musical hobbyist. He could sing and tap dance and play a bit of guitar. He wanted me to work in one of the shops that he owned. But when I told him I wanted to be a professional musician, he backed me all of the way. But he also taught me the importance of selling products at a very early age. He was very business savy. Advertisement

When I was 15, I came to London to do a recording. Mitch Mitchell had already played on the recording as a session drummer. Mitch and I got along, he was very nice. I soon met Jon Hiseman who was playing with The Graham Bond Organization after Ginger Baker had left. Mitch and Jon were the “hotrods” in town when I first arrived. I joined Chris Farlowe and the Thunderbirds, who had a hit single called “Out of Time” that was written by Keith Richards and Mick Jagger. When I left Chris to join The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, but I asked Chris if I could come back if Arthur Brown didn’t work out. He told me that if I wanted to do that, then I had to find a drummer to take my place. So I got Johnny Bonham the gig with Chris Farlowe. John hit harder than I did because he was really strong from working with his father’s construction company, he had a very strong right foot, as we all now know.

When I heard (English jazz drummer) Kenny Clare, I asked him to give me lessons. Kenny was too busy at the time, but he found a great teacher for me. He was an American drummer living in London by the name of Bruce Gaylor. He was my first teacher, and he was amazing.

MD: What did Bruce teach you?

CP: Bruce was as student of Henry Adler and Jim Chapin. He taught in the basement of Boosey and Hawkes in London. The first thing that he did was have me change his drumset to how I wanted it to be set up. He wanted to see how I was setting up my drums. Advertisement

MD: What a great first lesson.

CP: He told me that “ergonomically” the way that I set up the drums wasn’t going to work. He told me that we wanted my legs to be angled downward from the base of the spine, NOT upward or parallel to the ground. That way you could get some of your weight into the bass drum, and you could keep the weight off of your back. So we raised the stool to the right height to create that angle, which also meant that I had to slightly angle the snare drum. He had me lower the ride cymbal so there was no tension in my right arm, and both of your arms were in the playing position.

We spent some time learning how to play swing time on the hi hats. When many drummers were riding the hi hats, they were opening them too wide. He told me that the two cymbals had to be “sexy” with each other and be close so they could shimmer. He had me keep them closed a bit and I controlled the tension between them instead of opening and closing them. That produced such a better sound. We spent a lot of time on the jazz cymbal beat, the jazz ride rhythm. We did a lot of reading and technique, I played rhythms with my left hand while I played the jazz ride pattern, it was fantastic. I studied with Bruce for 18 months, and thinking back on what Bruce taught, he really knew his stuff and set me on a straight path in drumming.

I had a lot of teachers in my life. Early on, I studied drumset with Tommy Cunliffe, Lionel Rubin, and Max Abrahams too. In my 20s at the Royal Academy, I had Gilbert Webster, and I studied orchestral percussion with James Blades at the Royal Academy. Advertisement

MD: Tell me about Kenny Clare?

CP: He was one of the most phenomenal drummers that England ever produced. He played double drums with Ronnie Stephenson on a record called Drum Spectacular. He was a great musician that played with everybody. Those who know about him, know him from playing double drums with Kenny Clarke in the big band that Kenny Clarke and Francy Boland co-led. I saw Kenny Clare with Jack Parnell and John Dankworth. He was one of the first drummers in England who had military drum training and had been in a military orchestra. His reading was impeccable, he could play anything. For about 10 years or so he did TV work, theater work, was first call for recording sessions, you name it. He had this amazing technique, I saw him play on TV first, then a few months later he came to my hometown with John Dankworth and they played in the park on a Saturday afternoon. He was a phenomenal technician, an unbelievable reader, and one of the nicest men that I’ve ever met. When we met, I sat down with him and played on a drum pad, and although he didn’t have time to teach me, he made sure that I got the right kind of drum education. But he died young at the age of 54.

He played one drumset for his entire life, he bought it from from Manny’s Music in New York City. It was a white marine pearl Ludwig & Ludwig in 13, 16, 18, and 22, with two different snare drums. Gary Allcock still has those drums and thankfully he has kept the set together through all these years. That set is a big part of the English Drumming heritage.

MD: What is your favorite Kenny Clare recording?

CP: Drum Spectacular is my favorite. And you don’t only get to hear Kenny, but you get to hear Ronnie Stephenson too. Ronnie was one of the first jazz drummers to start playing matched grip.

MD: Did you know or get to see and hear Phil Seaman?

CP: Yes, he was phenomenal, a great reader, but he just got too involved in drinking and drugs. He was the first drummer in England to play West Side Story (the musical) in the theater. Kenny Clare played it after Phil. Phil was one of the all-time great jazz drummers, but he made a living in theaters. However, he wasn’t always straight enough to do theater work. Advertisement

MD: Since you are 72 now, and because Bruce Gaylor set you up so well ergonomically early on, have you had any physical issues that were drum related?

CP: No, never. Everything that could go wrong physically will happen via the back. The angle from your lower back to your legs is so important. If the angle is too small, it causes a lot of pressure on your lower back. If you can get that angle right, it alleviates the pressure on your lower back and any pressure or pain that would create. Doctors have told me that if you get that angle correct, it will almost self-correct everything else. The only other issue to sort out is how high your ride cymbals are. I know that some crashes have to be higher, but the height of the ride cymbal is very important to eliminating fatigue.

There is always going to be people who sit low and have no problems. Look at Tommy Aldridge, he has been sitting low forever, and he’s as fit as a fiddle. But then look at Phil Collins, and the awful angle between his lower back and legs, I feel very badly for Phil.

I have had both of my hands operated on for carpal tunnel, but that was from doing martial arts, and practicing karate for about 17 years. It had nothing to do with drumming!

MD: How are your ears?

CP: My ears are perfect. And I’ll tell you why. I’ve never used in-ears, I think they are too direct. I rarely even wear headphones. I don’t even have a stereo monitor mix on stage. I have one monitor with a 15” and a horn, and it’s pointed out towards the audience. It doesn’t even face me. I don’t even put my drums in my monitor mix. If you don’t have the drums in your monitors, you’ll hit at the temperature (velocity) that you want to play. All I have in my monitors is the vocals, the lead instrument, and a little of my right bass drum. I already have the musicians amps next to me, so I get some bleed from then anyway. I also get some of the sound from the monitors in front, so that suits me just fine. Advertisement

MD: Do you wear earplugs on stage?

CP: No, but I do have a pair of custom molded earplugs that I will wear at rehearsals to elmimnate some ear fatigue, because rehearsals are usually longer than the gig.

MD: You have been in the music business for a long time, and you have had some ups and downs business-wise, do you have any business advice for musicians who are looking to equal your longevity in the music business?

CP: I have been a professional musician for 56 years. To be in this business a long time, you do have to make good health a consideration. Drumming is physical, but we have already talked about that. Looking after your health and getting a good education is always given to me. Whatever you do in life, you MUST do that.

MD: I agree.

CP: This is a business, and you have to approach the business seriously. As a drummer, I believe that you have to make a choice between two things.

Choice one: Do you want to roll the musical dice and get into (or start) a successful band and learn everything that goes on in the business structure of a band. If you learn all of that correctly, (and there is a lot to learn,) you will be able to go from one successful band to another. In that process you can bring all of what you have learned along with you, and you will become the person that people ask for opinions. When people along the way have asked my opinion, I would always have the best interest of the band at the forefront. I always acted honestly. I have become the referee in many situations, and because I was always honest and truthful, people always respected my opinions. Honesty is hard, and you lose friends sometimes, but if you can be diplomatic in your approach, people will respect you, your honesty, and your opinions. Advertisement

When we started Asia, everyone knew that I wasn’t going to walk in with a suitcase filled with songs. John Wetton was the tunesmith. But if John wrote something that didn’t give me chills or didn’t have a chorus that was worthy of him, he knew that I would suggest that we look at it again. In music, the payoff to honesty is that there will come a time that people will trust you not only with their business, but with their music. When I was asked to join Asia, I insisted that everything be split right down the middle, everyone should be an equal partner. I could talk all day about that process, but that’s the long and short of it.

MD: Honesty, what a concept?

CP: However, some musicians don’t want you to be honest. I don’t get “liked” by other musicians because of my honesty. But in time, my honesty has shown other people the truth, and in time they have come to appreciate it. I’m not always right, nobody is. But I am honestly trying to be right and show others the right way. So that is one way to go.

Choice two: Play with other people and play with everybody. But if you do that you won’t have any residuals coming in, and you’ll have to be playing constantly. And that’s fine. The best example of that is Steve Gadd. Steve is one of the greatest human beings that I have ever known. He is a great musician, and he has played with more legendary musicians than anyone else in music history. I have the deepest appreciation for Steve as a musician and as a person. Advertisement

In my opinion, those are the only two paths to take. And either path is worth taking and important. I think of it this way, you have to have a way to make money while you are at home lying in bed. If you don’t figure that out, you have to go to the theater or the club every time you want to make money. A successful band that owns their own publishing has income coming in all of the time. ELP has never given away any of our publishing. Labels have leased the publishing for periods of time, but after that time period is up, the rights come back to us. That all goes back to what I talked about earlier. I learned early on from my step-father about always having something to sell.

I’m not super clever, I have made some good decisions along the way. Arthur Brown was the beginning of the psychedelia movement, ELP was at the forefront of what was called progressive, and Asia was at the beginning of the whole corporate rock thing, so I have made some good musical decisions. I picked up a lot of knowledge over the years, and when you have been doing something as long as I, you better have been able to get something right. It’s better to make a mistake and stick your foot in a bucket, and learn from that mistake. Because if you don’t try something once and make a mistake, you’ll never try anything. But in the end, you can’t substitute all of business knowledge and meeting all of the right people, for dedication to your music and practice.