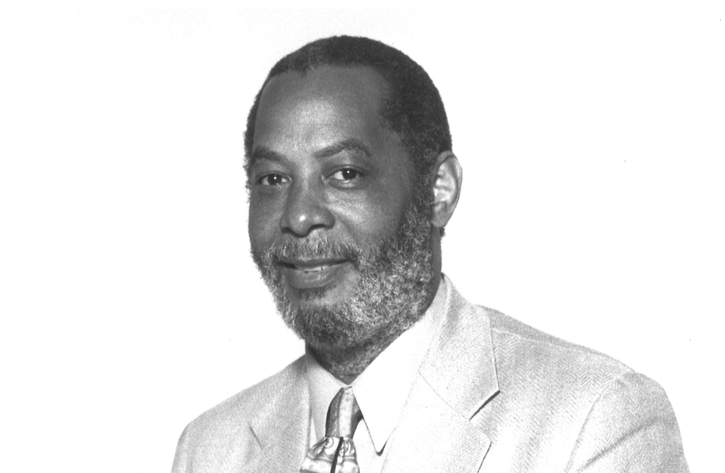

Ben Riley: Making History

by Jeff Potter

Ben Riley passed away on November 18, at the age of eighty-four. In honor of his historic career, we’re presenting this interview with him, which first appeared in the September 1986 issue of Modern Drummer magazine.

Fame? Ben Riley doesn’t ever recall having had the feeling of being “famous.” It’s a word he avoids. Although he says a friend once called him “jazz’s best-kept secret,” the jazz drummers’ community holds his authoritative playing in the highest respect. It is true, however, that Ben never received his fair share of media attention. His face wasn’t often found in the music magazines, but musicians who demanded superb drumming already knew what the public was slow to discover.

In the first half of his career, from the mid-’50s through the late ’60s, many of the great figures in jazz were supported by Ben’s graceful talents, including Sonny Rollins, Junior Mance, Ahmad Jamal, Stan Getz, Roland Hanna, Eric Dolphy, Woody Herman, John Lewis, Kenny Burrell, Walter Bishop Jr., Sonny Stitt, Billy Taylor, Kai Winding, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Nina Simone, and Johnny Griffin. But the crowning gig that secured him a place in jazz history was his four-year stay (1964-67) with jazz’s unpredictable individualist, Thelonious Monk. Advertisement

Recording with Monk during the Columbia Records years, Ben put to vinyl some astonishing classic examples of melodic drumming. Albums such as It’s Monk’s Time, Monk, Underground, and the recently issued 1964 live recordings Live at the It Club and Live At The Jazz Workshop demonstrate how Ben not only swings the band, but also coats Monk’s music with brilliant coloration. With credentials like these, how could Riley not realize the significance of his musical contributions?

An answer occurred to me while I sat with Ben over lunch at Sweet Basil’s jazz club in Greenwich Village. Several people who happened into the club came up to greet Ben heartily, and a few acquaintances waved from the street as they passed by the glass-walled cafe. Knowing that Ben has been living on Long Island for many years—fifty miles away from the Village—I commented, “It seems you know just about everybody on the block!” “No, not really,” laughed the sad-eyed, salt-and-pepper-bearded drummer as he sipped his coffee. “It’s just that I’ve played around here since they first put the door on this club.”

There lies the key. On a worldwide scale, it is much the same. Ben never exploded on the scene with a sudden glittery media-attracting splash. He has just always been there: a deep-rooted, consistent pillar of excellent musicality in jazz drumming. Some artists—such as Monk, whose face appeared on the cover of Time—were lucky enough to see concrete media evidence of their renown. Ben, however, is an artist who quietly climbed to artistic heights without the media’s herald trumpets, and now rightfully stands as one of the jazz drum masters. As Monk once prophetically told him, “You’re a part of history, and you don’t even realize it.” Advertisement

After the Monk years, the stress, strain, and discouragements of the business side of music collapsed on Ben, and he exiled himself from music entirely. Leaving music for four years gave him a better perspective and a new strength to return. He speaks of these soul-searching years with a soft-spoken voice that reveals hints of wounds that have only now been soothed by the wisdom of maturity. The lessons he learned are food for thought for any aspiring artist.

Since returning to the scene in the early ’70s for the second newborn half of his career, Ben has worked with acts such as the New York Jazz Quartet (with Ron Carter, Frank Wess, and Roland Hanna), Carmen McCrae, Alice Coltrane, the Ron Carter Quartet, and the Jim Hall Trio. He has also traveled to the Soviet Union with a group featuring Toots Thielemans, Milt Jackson, and Bob James. In 1984, Ben began playing with South African pianist/composer Abdullah Ibrahim, a.k.a. Dollar Brand. He continues to play dates with Ibrahim’s big band and also played on its last album, Ekaya.

The group that is an ongoing love for Ben is Sphere, which he co-founded with fellow Monk alumnus and tenor saxman Charlie Rouse, pianist Kenny Barron, and bassist Buster Williams. Sphere—which has two domestic album releases, Four in One and Flight Path—features a healthy serving of Monk tunes in its repertoire. Rather than just rehashing Monk tunes in an overly familiar way, the group maintains the balance between preserving the authentic spirit of the music and contributing its own fresh perspective. Monk would have wanted it that way. Advertisement

At Ben’s last date at the Village Vanguard with Sphere, his playing was as sharp and alive as ever. His intuition for complementing soloists and his sensitivity to dynamics are masterful. Plans for his own recording project are now brewing in his head. Perhaps these future plans will make more history—whether he realizes it or not.

MD: Sphere seems to be the group best qualified to carry the torch of Monk’s music.

Ben: Sphere was formed the same year that Thelonious died. We formed the quartet just before he became ill. We were searching for a name for the band, because there was no one leader in the group. The name Sphere was suggested by Kenny Barron. The rest of the band said to Kenny, “Well, you know that Sphere is Thelonious’s middle name?” And Kenny wasn’t even aware of that! So, it was very strange, because of course, we were also playing some of Monk’s music in our repertoire. Just before Thelonious became ill, we called his family to find out whether or not they would have any objections to us using the name, and they didn’t. On our first album, Four in One, we recorded all Thelonious pieces. It was strange: The morning we went in the studio was the morning he passed away. We didn’t find out until after the date was over. It was eerie. The whole day had felt strange to me, and I had no idea of why that was. When I got home, I found out what had happened.

MD: It must have been tricky handling that music, especially since you and Charlie Rouse are Monk alumni. Did you find you had to be conscious of being more than just a “tribute band”? Four in One turned out to be much more than that. Sphere has its own personality. Advertisement

Ben: Yes, we did want to establish the fact that we weren’t like the Mingus Dynasty band. However, we will always play and record music that belongs to Thelonious’s company. There are a couple of tunes under litigation that we would love to record. But for now, why record something that we know will not go to his own company—tunes that are controlled by his family? He has so many tunes that most people are not familiar with. He has written quite a lot of songs that don’t get played much because they’re hard. It’s not the easiest music to play, first of all, because it’s such personal music. Thelonious is one of the few composers whose music has to be played almost note for note to make it sound like it is supposed to sound. Most of his music plays itself. The beauty of it is the simplicity. If you avoid overdressing it, you are warmed by what he has written. My greatest experience with that music was when we played it with a nine-piece orchestra, because I could hear all the colors.

MD: As a piano player, Monk not only had his own sound, but also a quirky kind of swing feel. You and Rouse complemented him so well in that kind of feel. It was almost more of a dotted-note bounce than a triplet-implied swing. When you joined Monk’s group, after having played with a lot of other jazz leaders, did you feel that you had to shift gears to be compatible with the Monk swing feel?

Ben: He had a great sense of time and rhythmic construction. I played two or three different ways in that band until I felt comfortable. Certain tunes dictated that I find another way to interpret the beat. I got more into a Shadow Wilson style of playing later on, because it left a lot of space for the other musicians to do what they wanted, and it didn’t dictate what was happening. Thelonious would always drop one-liners on you. Instead of telling you what to do directly, he would give you a little hint, such as, “Because you’re the drummer, it doesn’t mean you have the best beat.” He said, “You can’t always like every song. Another player might like the song better than you; his beat might be better than your beat.” Advertisement

What he was saying was that you should listen first before you take control and find who has the swing in the beat. And whoever has the best beat—that’s the one you join. After years of playing together with Sphere, we find that we listen more to each other. And that has to do with that idea of time and feeling: The others will join whoever has the best feeling at a particular time.

MD: Monk’s comping style was unusual. His left hand dropped in some surprising harmonic/rhythmic accents. Some drummers would have been startled by this.

Ben: It makes you think, and it demands that you become involved in the music. Rather than just counting bars, you have to become melodically involved in it. It’s almost like working with a singer.

MD: You’ve been called a “melodic drummer.” Do you think of your playing in those terms?

Ben: There are theatrical players, and there are melodic players. I think I play the melodic style, because I worked with a lot of trios and singers. Also, in the era I came from, there were more “melody” songs. In order for a drummer to be really involved, he had to learn the melodies and verses to really be in tune with what everybody else was doing.

MD: Even your soloing shows this melodic structure.

Ben: I think listening to Max Roach caused me to start doing that. If you really listen to Max, you’ll notice that he plays the melody all the time. Many drummers who have experience with melody play “melodic” even if the tunes are more abstract. For instance, in Elvin’s playing with ’Trane, there was a melodic structure set up. Even in Ornette Coleman’s music—which a lot of people say is just “out”—it’s all melodic if you listen to the rhythmic structure of the horns and rhythm section. I’ve always been conscious of playing with structure. Some people just go “out there” with no way of getting back. Sonny Rollins used to say, “When you play, it’s like driving on a highway you’ve never been on before, but there are always landmarks. You have to make those marks.” Advertisement

MD: As a leader, Monk had a strong personal concept. Did he expect you just to pick up on what he was creating, or did he look for ways to coax something special from you?

Ben: For the drums, he allowed me the freedom to find what I could do to enhance what was happening. Plus, he never played anything he didn’t think a player could handle. He would play just enough music, and then when he thought you were comfortable with that, he would step up to other things that might be more intricate.

On my first job with him, we had had no rehearsal. We went right to Europe, and he just played. Later on, he said, “If I didn’t think you could handle it, I wouldn’t have hired you.”

MD: On some of the records you cut with Monk, proper sideman credit is not listed. It shocked me to see one liner-note article that simply referred to “a bass player and drummer.”

Ben: I can only offer theories on that. I know what you’re talking about. But I hate to think why that may be. Sometimes, when records are reissued, the record company only wants to think about the artist and doesn’t want to bother repaying the sideman. I have been finding a lot of records in Europe now that Larry [Gales, bassist] and I were on, but we didn’t know anything about them until we got over there.

MD: Do you believe that part of the reason you were overlooked in the media was due to the fact that you were in Monk’s shadow?

Ben: Basically, I think it was because I am not a flashy person. Media people tend to write about flash; they don’t listen. If they don’t see anything flashy, they can’t hear anything. This is a very visual age. Advertisement

MD: Ironically, that may have been part of the reason why Monk hit the cover of Time. Although his music alone merited the honor, he may have drawn cover attention also because he was a colorful, eccentric person.

Ben: It took the public a long time to realize what a genius they had on their hands with Monk. And some media people said discouraging things about Thelonious. When I first started with him, I read reviews. He said to me, “Until I tell you that you’re not doing what I want you to do, don’t worry about it. They don’t know what I’m doing, so they can’t

know what you’re doing.” So that kept me from being overly concerned about the media.

Everyone would love to have the media be enthusiastic, but it takes longer for some people to get the attention, and some players never get it. I’ve heard players who I thought were some of the world’s greatest, and no one has ever heard of them. So at least I am fortunate that I’ve had some visibility through Thelonious. Later, I gained visibility from a whole new younger audience playing with Alice Coltrane. Advertisement

MD: Playing with Abdullah Ibrahim is another situation in which the leader has a very personal feel.

Ben: Abdullah is from a different culture. Here’s another person with a different approach to time and beat. It’s very different from what we’re accustomed to. It is more in the vein of a laid-back style or an early rock thing. There is an African drum influence, so you have to lay back and let that take precedence over what you do. I can’t stay on top of the beat with him. In a way, that’s like Thelonious: He wanted me there, but not to force it. When I first joined Abdullah’s band and we did the first rehearsal, the musicians approached the music like a Western band—playing a little too “hip.” But with him, you can’t play like that. There may not be as many notes, and you have to set up each one and make it be something.

On the drums, I have to take the rhythm and expand it. Rather than try to do too much at one time, I have to build it—see how far it can go, and then change the accents and colors. I enjoyed it, because it demanded that I think in a different way and approach the music in a different way.

MD: I understand that you are basically self-taught?

Ben: I started by myself and then studied in school. My first teacher was Cecil Scott, a sax player who had a big band in the days when Harlem was hot. The first place I ever worked was at the Sudan club with his band on Sunday afternoons. Advertisement

When you first start playing, you idolize certain players. So, at one time, I tried to play like Max Roach, and then I heard Art Blakey and incorporated that into my playing. Then I heard Philly Joe Jones, and that impressed me. But the biggest impression came the night I heard Kenny Clarke. From then on, I tried to be everywhere he was working. I loved the way that he was not over the top of anyone, no matter who he played with. He was always right underneath and would always build. He uplifted the music without overpowering anyone, and that is what impressed me about him. I decided that was the way that I wanted to play.

But most important, I wanted to be a well-rounded player. I still don’t really feel that I’m a soloist. There are times that I have something to say, but I don’t have to take that much time to say it. I just want to make that statement and go right on with the music.

MD: With Monk, you had plenty of extended solo space.

Ben: Monk made me do that all the time.

MD: Made you!

Ben: Well, rather, he would inspire me to do it, because he would leave space for me and I had to do something. [laughs] So, yes, I guess in a way he made me get involved and think of structural playing. I would think, “Okay, I don’t know how long he’s going to leave me out here, so rather than just do something haphazardly, let me structure it the same way as the song is structured.” Each time I played the songs, I could add on because I had the melody in my mind, and I could embellish and stretch in and out of the melody. Advertisement

Working with Sonny Rollins got me into thinking about how horn players phrase, and I started to apply that phrasing to the drums. That’s another one of the reasons why I got into melodic playing. In the era I came up in, there was always someone around to inspire you or say something to you that would help you to think about what you were doing. They would make suggestions without making suggestions. The first time I met Kenny Clarke was at Minton’s. I was playing, and I looked out in the audience and saw him. I tried to play as best as I could and as much stuff as I could think of. When I got off the bandstand, I went over to meet him and he said, “Yeah! That was wonderful. Let’s go downtown and hear so-and-so.” I said, “I can’t. I have to stay here and work.” He said, “Work? You mean to tell me you’re going to play something after that?” [laughs] It made me stop and think. He was telling me that I had to take my time and use my space—put it in order. You can overplay without realizing it. You have to learn what not to play.

One of the things I enjoyed about playing with Monk as well as Sphere was that we didn’t always play the same tunes in the same tempo. When this happens, you can’t come in and develop “cheats.” Since each tune could be in a different tempo each time you play it, the things you played before won’t fit the next time, so you always have to approach it differently.

That’s one of the great lessons that I learned from Thelonious. He played what we used to call “in between tempos.” He used to say, “Most people can only play in three tempos: slow, medium, and fast.” So, he played in between all of those, and we had to learn how to feel that beat. In certain tempos, you would be in big trouble trying to count, so you would have to feel the structure. Advertisement

MD: I remember a rare famous DownBeat blindfold test with Monk. He had plenty of unusual responses; it was a riot.

Ben: I’m sure it was!

MD: At one point in the test, Leonard Feather commented, “Did I hear you say the tempo was wrong?” and Monk replied, “No, all tempos are right.”

Ben: Right. He felt that any tempo we played was alright as long as we made it happen. There is nothing wrong with a tempo: It’s what you’re doing with it. In my first experience with him, in Amsterdam, we played “Embraceable You” as a very slow ballad. Then he went into “Don’t Blame Me.” He stood up, looked over to me, and said, “Drum solo!” Fortunately for me, I’d been working at the Upper East Side supper clubs playing a lot of brushes, and I like brushes. So when I played it, I didn’t have to double the tempo, because I was used to playing slow brush tempos. I played it right at the tempo he gave me.

When we were going back to the dressing room, he just walked by me and said, “How many people you know could have done that?” and he kept on going. You see, I’d asked him for a rehearsal and he said, “What do you want to do—learn how to cheat?”

It was like going to school. He would always give you a little test. If he thought you had a hold on what was happening, he would do something to test you to see if you were conscious of where you were and what you were doing. At any given moment, he could do something so abstract that—if you weren’t aware of what was happening—you were finished. Advertisement

One night, Rouse, Larry Gales, and I were playing good, stretching out, and having a ball, and Monk was strolling. We were playing on the wrong beat, but we didn’t realize it. We had lost the beat completely, and at first, I think Monk thought that we did it deliberately. Then, after he sat there for a few choruses, he got tired of listening to it. At the beginning of the next chorus, he dropped his hand down on the piano and said, “One!” That was like somebody slapping you in the face. [laughs] Fortunately, Art Blakey had told me certain little tricks for getting back in right away.

MD: What did he tell you?

Ben: He said, “Roll!”

MD: It seems that an open mind and cool head are character traits that you needed for handling that gig. Many other players might have lost their cool if they were surprised on the spot with a ballad brush solo.

Ben: I knew he wasn’t trying to hurt me. In the era when we came up, nobody tried to embarrass anybody.

MD: That seems hard to believe. What about the famous cutting sessions?

Ben: Other people called it a “cutting session.” It was stimulating for you to play with another musician who was equal to or better than yourself and to find out just how much that person could really do. It was a friendly situation. Today, I sometimes feel hostility from players when they come in on someone else’s job; it’s almost like they’re going to war. It used to be a war, but a friendly one. Advertisement

MD: Like padded boxing gloves?

Ben: Yeah, you were seriously trying to blow the other player away; don’t misunderstand me. Everybody was trying to be the top, but it wasn’t malicious.

MD: Do you think today’s malicious situation is due to increased competition and the shortage of jazz work?

Ben: No. The society as a whole is too violent. The whole value we once had for the arts is not there. It has been made so much a business and so competitive that there are literally people stabbing each other in the back. For jazz, there’s not that much work, and there’s not that much even for crossover. It has caused a war out here. It is really hostile, and it has nothing to do with art. That’s sad.

MD: Monk was somewhat of a music philosopher. Did his philosophies influence your playing?

Ben: He told me, “You have already learned how to play correctly; now play wrong and make it right.” That is like life: There are situations in life that you can’t find in any textbook. So the true challenge is to find what you can do with life when it goes wrong.

MD: A musical example comes to mind. Monk’s ballad “Ruby, My Dear” is loaded with dissonances, yet he makes it work as a beautiful, lyrical ballad.

Ben: It’s beautiful. That is an example of hearing a note in your mind, feeling it in your heart and your mind, and then letting it come out. It takes a very sensitive and warm person to accomplish these things; it means giving. We have a lot of takers; we don’t have many givers. The music and the music business have suffered because of this. Advertisement

MD: You’re a master at drum coloration.

Ben: I try to find colors that make the music move and float along. Finding the right kind of cymbals is important for this, as well as staying in the right frame of mind. You can hear it in Sphere.

MD: How have you chosen your cymbal pitches? I noticed in one of your Sphere solos how you framed drum licks within a repeating cymbal pitch pattern.

Ben: The cymbals are related in a heavier versus lighter way, although I can’t say what the specific pitches are. But I have really spent time looking for cymbals for different colors. I use one that has a soft sizzle sound, even though it’s a flat top! Everybody’s amazed when they look at it. It’s an A Zildjian. Another old one that I used with Thelonious and still use is a heavy A Zildjian. I also use a Chinese cymbal.

I have a tuning style on the drums that is a little different. When I worked with Kenny Burrell, I tuned to his guitar and the bass to get the drums tuned into their ranges. Since I started working with Abdullah, I have had them tuned real deep because of the African sound. With Sphere, I take the tom-toms up a little from that.

I’ve always listened to other players to find something new to challenge myself with. I get my greatest thrills listening to pianists, because they have so many colors to work with. When playing with pianists, I try to place my head into where they are coming from. I’m thankful to Thelonious for making me become a listener. A lot of drummers are not really listeners. I’ve heard some new young guys like Smitty Smith and Jeff Watts who really listen. There are so many talented young people today that it makes me glad that I’m involved with music again. Advertisement

MD: Could you talk about the period during which you left the music business?

Ben: I stopped playing for almost four years. It just got to me to the point where I was drowning in it. I saw that I was being used and abused, and I just had to step away from it.

MD: The business side of music?

Ben: Yes. I think that’s what happens to a lot of people: They suffocate and don’t know why, so they won’t get away from it to get a look from a distance. When I stepped away from it, then I had a chance to breathe. At that time, I wouldn’t even come to Manhattan to hear music. I didn’t want to be around music at all. It got to the point where I was really sick. The business and the personality conflicts—people bickering and stabbing each other in the back—I just had to get away from it.

MD: You didn’t play at all?

Ben: No, I didn’t play at all. I wouldn’t even turn the radio on. I worked in audio-visual at a school. I needed to clear my head. My life had been so wrapped up that I had forgotten I had a family. It wasn’t a happy time for me or my family. I had been going for about ten years straight with this constant push: always pushing and fighting, ducking, dodging—and drinking. One thing got on top of another.

Finally, I thought, “If I get away from it, I’ll find whether I really want to deal with it or not.” Fortunately, when my boredom started driving me to drink, that’s when my friends Alice and John Coltrane started trying to talk me into coming back, and Ron Carter insisted that I do some playing with him. That is what got me back on a roll. Advertisement

MD: Was that frustration a result of what you have described as today’s demise of the music business?

Ben: Oh, yeah.

MD: Did you feel this during the Monk years?

Ben: It was building then. In fact, it was after I left Monk. I just said, “I can’t play.” I couldn’t feel anything. For that period, I had lost the desire. It was a frustrating time for me, because I saw so many things that I knew were wrong and I just couldn’t convince anybody else of it. In this business, you see things at times that maybe you shouldn’t see, because they destroy the whole concept of the beauty that you have in your music.

MD: What were some of these things that ruined the music?

Ben: I’m talking about record companies, managers, promoters—you watch them taking advantage of you and taking all of the money. You see people sell themselves to the person who is robbing them anyway.

MD: Was Monk’s group a victim of this exploitation?

Ben: It happened with everybody, not just Monk. I believe this has been going on ever since. Now, when musicians deal with their own peers and they don’t give a damn—you can understand the reasons why some musicians use drugs and some become alcoholics: They’re handcuffed. If you’re a strong person—who cares? Advertisement

There are 10,000 more people coming up, so if you don’t want to accept a bad deal, someone else will. And that’s why music has gotten to the stage that it has. First of all, we as musicians have to respect what we’re doing. It’s like anything else. If you’re a lawyer and don’t respect your profession, naturally, you will become sleazy. We musicians have allowed this situation to come into our community, and it has almost destroyed us.

MD: You’ve adapted well to many different artists.

Ben: As a drummer, you have to find out what is best for the people you’re working with. Then, you incorporate what you do. Most drummers go into a gig and say, “Okay, I’m the drummer. Just give me the tempo.” But hey, that’s not the whole job. The whole job is to hear what they’re

doing in that tempo, make the colors, and make the person who’s playing happy.

Speaking of different styles, I even played a set with the Grand Ole Opry when I was in the Amy, because the drummer was late! I’ve played everything from jazz to the Opry to bar mitzvahs to Latin music. When I went to Russia, I even played with a balalaika band! The way I approach drums is due to having been exposed to different musical experiences that I draw from. Advertisement

MD: I would like to go down a roster of some major artists you have worked with and learn how you adapted your drumming to support them. First, how about your work with the double tenor team of Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis and Johnny Griffin?

Ben: That was my first real road experience with a band. We traveled in a station wagon from New York to California, down South, and through the Midwest. I had to be very hard-driving when I played with them. We played very fast, and I had to think fast and have stamina. To keep up the intensity, I had to learn how to be mentally tough, so that I wouldn’t have to play as hard. A lot of people play hard with their shoulders and arms. But if you keep a mental toughness, you can get that sound without using all of that strength. This taught me how to pace.

I had two very individual stylists to accompany. So I had to give Johnny and Eddie different things. With Johnny, I could open up more and get busy. With Lockjaw, I got into the basic groove, laying down a heavier four feel, so that he could float over it. Junior Mance was on piano, and I had to play differently for him also. At that time, Junior was all reckless abandon—like we all were, being so young. It was a matter of me holding everybody together and being an anchor for Junior. Advertisement

MD: And with the Woody Herman sextet and big band?

Ben: I only played with the big band for about two months and a little longer with the sextet. They were going to Texas and Miami, but in those days, mixed bands couldn’t stay together. I would have had to go across town and stay in a different hotel. Woody is a gentleman and I loved working with him, but I decided not to go. For Woody, I couldn’t play like I did with Monk—settling into whoever had the best beat. The tempo was basically on me, because it was a big band.

MD: Sonny Rollins?

Ben: We didn’t use piano, so that was another very different experience for a drummer. It was Jim Hall on guitar, Bob Cranshaw on bass, and me. Sonny was my main phrasing influence. Freddie Hubbard came down to see the group at the Jazz Gallery, and he said to me, “What are you doing playing melody?” [laughs]

MD: How did the absence of piano affect your approach to the drums?

Ben: That’s why I had to start thinking like Sonny was thinking. He had Jim sometimes playing and sometimes not. Sonny was hearing all the chords he needed to hear and most of his stuff was based off of what Bob Cranshaw and I were doing. So I tried to follow his phrasings. I couldn’t tell what all the piano parts were that he was hearing, but I could hear his colors. Advertisement

MD: When you were coming up, Harlem was alive with jazz. What was that like for a young, growing drummer?

Ben: There was music seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day. You could watch and learn from the masters, and get their good advice. There was always somewhere to play. When they strangled off Harlem, that killed it all, because Harlem was the schoolyard. You could meet all the musicians there. All the uptown and downtown players would meet at those little clubs. You got a chance to sit in, too. In those days, we drummers hung out together. Today, you hardly see that anymore—that exchanging of ideas and experiences. One of the great things about working at all the black theaters was that we were all in that circle that worked New York, Baltimore, Philly, Washington, D.C., Chicago, and Detroit. We traveled with one particular show, so people had a chance to practice with each other every day.

MD: Who were some of the drummers you used to share ideas with?

Ben: Mickey Roker was one. Willie Bobo used to show me timbale things, and I would show him time things. Clarence Johnson was the best reader, so he would help us; he brought books to the theater every day. During breaks between shows, we went way up in the crow’s nest away from everybody and worked on things.

MD: Do you still do much playing abroad?

Ben: I have been going to Europe regularly for the last three years. I’m going again this year with Sphere. We finished an album on Red Records that will only be released over there. I also have concerts and a record date with Andrew Hill in Italy. Advertisement

MD: The trombonist, Roswell Rudd, who loves Monk’s music, was once speaking about Monk and an enthusiastic young piano student told him, “I would love to study with Monk. Do you think he would be willing to give me a lesson?” Rudd responded, “He may, but you would have to be prepared for anything. He might sit down with you at the piano, or he might take you for a walk and point things out to you.”

Ben: That can be teaching. I remember that Sonny Rollins told me, “Practicing doesn’t have to mean sitting down with your instrument.” There are certain experiences in life that you incorporate into what you do on stage. Sometimes you have something in your mind and you can’t get to your instrument, so you map it out in your mind. When you get to your instrument, you’ll be amazed at what can happen because of that.

I try to keep aware of the aesthetic beauties around me. I guess that’s why I play the way I do: I’m a sentimentalist and a romanticist, although I may not always appear to be. I think that’s why I was attracted to Abdullah’s music: It has an airy quality with space that intrigues me. Advertisement

MD: When you returned to playing after four years, did your drumming gain a new maturity from the experience?

Ben: It was difficult to get back. The music seemed a light year away. Even now, I sometimes wonder if I can take this step, because people are quick and I’ve been away from that competitive edge. But I’m mentally tougher for it all. I just had to get back in and sharpen things up.

MD: Mental toughness certainly helps when taking care of business. In what way does it apply to your actual playing?

Ben: A lesson the old masters taught me was that, every time you play to the public—every time you get on that stage—everything up there is serious. You don’t get up there and not give your best. I’m out of that school, man. Even if I am feeling angry, I can’t go up there and not give. It’s sacrilege not to give. That is where the mental toughness comes in.

Some leaders used to make you angry deliberately to make you handle the situation. You would have to go up and say, “I’m going to play so good that I’ll make him sorry that he ever said that.” This business is hard on sensitive people who cannot sustain that kind of mental toughness; they will crack up, because there are too many people throwing darts at them. Advertisement

I usually advise young people who want to be drummers to finish school first. The business will always be here. Young people who quit, like I did, will be in the position that they have to make music happen, and that will put a double burden on them. The chances of you being discovered or widely pursued are…well, a good example is that this is the first interview like this that I’ve had, and I’ve been out there for over twenty years. [laughs]

MD: You mentioned to me earlier that you had an interest in gospel music.

Ben: I’m spiritually attuned to the Baptist, holy-roller music, because that’s what’s happening. That’s the blues, and you can’t get away from the blues if you want to play jazz. I didn’t play at churches, but I attended. That’s what made me begin my return to playing. I would listen to the choirs, and that would cleanse all of those negative things out of me. I still go. The only other place I have experienced that kind of feeling was in Africa when I was over there playing with Abdullah. We went to the bush and into a little fishing village. One night, the people gathered, brought their drums out, and we all played together. It was hypnotic. I knew drums were powerful, but I had never experienced that kind of power. They have a beat that is just—holy.

When I think about it, it’s awesome. The people I’ve been associated with have been some of the top, heaviest people in the business. I was just young enough not to understand how much was happening. I might have been scared to death if I’d realized what was happening. I didn’t realize, because I was so busy trying to improve what I could do to fit all the people I was playing with that I never had a chance to get an ego. Advertisement

MD: When did it finally dawn on you that you were a part of history?

Ben: When I stopped playing. A lot of people came up to me and said, “What’s happened to you? We haven’t seen you lately.” And I never realized that anybody even knew who I was. I was just happy that I was able to play. I’m still like that. I don’t hold importance on being a big-time whatever. All I wanted to know was, are the guys I’m working with happy with what I’m doing, and are the audiences happy with the music we’re giving them? That’s my greatest treasure, man. That’s the only thing I could ask for.

You don’t always realize how many lives you touch and how many people are watching you. There are people who will try to emulate you, so it’s important to consider what kind of person you’re going to show them. It’s a big responsibility. And when that dawned on me, man, I had to get away and think about it, because I was wild and crazy like everybody else.

This is a God-given talent we have; we didn’t just get it from school. We’re given it as our part of this universe, so we have to make use of it. I’ve seen a lot of young faces intently watching my every move. That makes me want to shine more, because I might do something that will make all the difference in the world to a young person. And if you have something spiritually uplifting to give to another human being that can help that person take one more step, that’s really what it’s all about. That’s why I love music; we’re only trying to give somebody a moment’s pleasure. I don’t think there is anything higher than that. Advertisement

MD: It’s hard for me to imagine climbing to your artistic level, becoming established, and then not even touching sticks for four years.

Ben: But I never accepted myself as “established.” I still don’t. I look at myself as being a person who has taken a step to one degree. I’ve accomplished something here, but I feel that there is so much more that I’m not doing—or am not aware of—so I can’t be complacent. There’s still more for me to accomplish, because I’m still here. I know now what I have to work on. Whether or not I can get it all done is another story. I’m pleased with some of the things I’ve done, but the greatest thing is to have people come up to me and tell me how much they have appreciated me over the years.

I’m working on a book now with Don Sickler that uses my drumming excerpts as examples of drum accompaniment styles. It was interesting to sit down and analyze my drumming, because it made me aware of things in my playing that I wasn’t conscious of. Don told me, “You’re the best-kept secret in jazz. Everybody talks about the masters, but people don’t even know that you’re one of the top guys.” I told him, “How could that be? Nobody knows!” And he said, “Wait until you see the response to this book.”

MD: It’s strange to hear you say that you felt nobody knew about you. So many jazz drummers would be shocked by that statement.

Ben: I never thought about it much, and I’m grateful to the Almighty that I don’t have to have that on my mind, because that’s a hindrance. Monk used to say, “If you pat yourself on the back, then you’ve lost the groove.” Advertisement