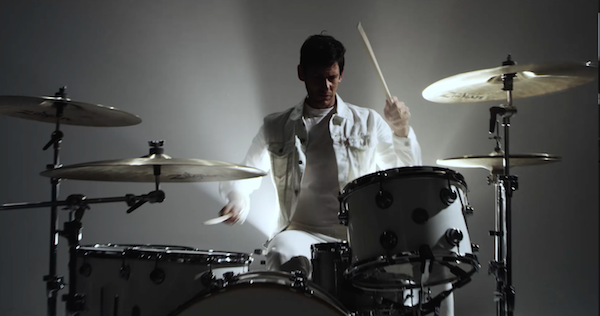

Adam Carson on AFI’s <i>The Blood Album</i>

by Willie Rose

This past January 20, the anthemic emo-punk band AFI released its self-titled album, aka The Blood Album, the group’s tenth record over the course of its twenty-five-year history. Along with searing hooks from vocalist Davey Havok, brilliant production and riffs from guitarist and keyboardist Jade Puget, and bassist Hunter Burgan’s unwavering foundation, founding AFI member Adam Carson unleashes an onslaught of creative drum parts and explosive tones throughout the album’s fourteen tracks. Here Modern Drummer Online explores the newest record and more with Carson.

MD: The drum are massive-sounding on the new record. What went into getting the sounds for this album?

Adam: Matt Hyde, our engineer and producer, Walter Earl, my drum tech, and I spent a lot of time dialing the drums in. We had two kits set up simultaneously in the tracking room. One was a bit of a “Frankenstein” kit—a DW kick that I’ve used on every record AFI has made since Decemberunderground paired with Gretsch 125th Anniversary–series toms. We would rotate snares and cymbals in and out on a song-by-song basis. We miked it up with more of a traditional close-mic setup on the drums and cymbals, and we used overheads in an X/Y stereo setup. That’s the main kit you hear on most of the album. On the other side of the room we had another setup. We called it the X-kit. It was an early-2000s Premier with a monster 26″ kick drum that sounded huge in the room. It was a bright Godzilla green—a bit hard to look at. We kept the tuning of that kit a little more open, and we used close mics on the toms and cymbals and a mono overhead mic arrangement on the front and sides of the kit. We had three different sets of room mics going, each with different processing.

Getting a big, slamming drum tone always starts with the drums in the room tuned properly and sounding great. Beyond that, you can use room compression to make things more overdriven. It’s a bit of a balancing act, however, because while the snare and toms sound more exciting with some compression, the cymbals can begin to wash everything out and become unruly. Every song seemed to call for a different combination of close, overhead, and room mics. A few tracks had to be tracked top and bottom, where I would do a pass with just kick, snare, and toms with the room dialed in to explode, and then another pass where I just played the metal. It’s a bit confusing to only track the cymbals, especially during fills, and it takes a lot of restraint to not embellish and end up with a bunch of parts that would take three arms to reproduce live. But if done properly, you end up with a great drum sound. Advertisement

MD: Were there two different snares used between tracks such as “Dark Snow” and “Aurelia?”

Adam: Between Walter and I, and Jeff Sheehan, the owner of Megawatt Studios, we had almost thirty snares to choose from, and we began each song by selecting the drum best suited to the sound we had in mind. For “Dark Snow” we auditioned a dozen snares but settled on a steel 8×14 Tama that had a sharp and bright crack that cut through the song’s heavy synth bass.

We probably spent the longest time dialing in the snare sound for “Aurelia.” The song calls for a really fat snare that takes up a lot of space and has a significant amount of attack without overwhelming the vocals. The reference I had was Don Henley’s “The Boys of Summer.” In that song the snare itself is almost a hook—it’s so distinct. It would have been easy to just track a generic snare and then add a sample to construct the sound, but instead we spent the better part of a day auditioning snares and messing with different tunings and dampening. The snare we finally chose was a Ludwig Black Magic. We tweaked the room mics on the X-kit to have varying degrees of compression, and then used a set of [Blue Microphones] Hummingbirds with a heavy limiter/distortion/gate that was keyed off the snare drum. At the end of the day we ended up with several versions of the song, all with different degrees of insanity on the snare, and we chose the version that fit the best.

MD: What was the writing process like for the new record?

Adam: In some ways it mirrored our previous records. The songs always start with Davey and Jade, who conceive the skeleton of the song and make sure all the parts are working with the chords and vocals. Then Hunter and I get involved, and as we work it out, each guy pushes and pulls at it and adds their influence and style to create their part. Eventually it begins to sound like the performance you hear on the record.

Advertisement

Adam: In some ways it mirrored our previous records. The songs always start with Davey and Jade, who conceive the skeleton of the song and make sure all the parts are working with the chords and vocals. Then Hunter and I get involved, and as we work it out, each guy pushes and pulls at it and adds their influence and style to create their part. Eventually it begins to sound like the performance you hear on the record.

Advertisement

This album was especially challenging—though ultimately rewarding—because the songs were delivered to me in full demo form rather than loose sketches. This can be a blessing and curse—songwriters take note. On one hand, with a fully realized demo, it’s clear what the song is about, what the different parts are doing, and how the instruments work together. It can streamline the process of working out the track as a full band. On the other hand, a lot of decisions about arrangement and transitions are predetermined. Some of the happy accidents or left turns that spontaneously happen when four guys work together on a loose idea are harder to come by.

But in this case it was the best of both worlds. The songs were really focused and arranged, and it became challenging to construct the best drum part that worked within those parameters. Sometimes it was a matter of ignoring or thinking beyond what was on the demo. And oftentimes it was recognizing that the demo had a lot of good ideas worth preserving, so my job became to add the texture and human quality of live drumming. At times, I found myself challenged by parts that I would never write for myself, but I agreed that they sounded pretty killer. So I spent time in my rehearsal space with a metronome getting comfortable with the parts. A lot of the time it was a matter of deconstructing the track and building it back up. Sometimes I ended up in the exact same place as the demo, and sometimes the drum parts evolved.

MD: What were some of the challenges that came up during the session?

Adam: From start to finish, this was one of my favorite records to make. I had done my homework going in and had a detailed idea of what I wanted to do, but there was still a degree of spontaneity to the session that kept it interesting. I got bogged down on a part a couple of times, either with performance issues or realizing a part I had written wasn’t translating and needed to be reworked. But I managed to work things out fairly quickly. Advertisement

It’s amazing how important it is to manage your energy levels and blood sugar, and just your general mood throughout a long day in the studio. One day during the session I was on fire. I was playing great, feeling creative, and making a ton of progress. We broke for lunch—which I skipped for some reason—and then some technical problem slowed us down getting back into the swing of things. By the time we resumed tracking, I could barely play the part I had previously been all over. And then the more I tried to concentrate and will my limbs to cooperate, the worse I sounded. I finally hung it up for the day, and when I came back in the morning recharged, I was back playing the way I wanted to. I have to give Matt a lot of credit for assessing and managing the vibe and tempo of the session to always get the best out of me.

MD: What was it like working with Matt and Jade as producers?

Adam: It was great and felt collaborative practically from the start. Like I mentioned before, Jade had fully produced demos as references for the songs, and they were full of great drum ideas. So it was a matter of making the drum tracks my own and adding my style and personality while preserving ideas that were integral to the song. Jade, as a producer, had an overview of the record, so he was able to inform me if a part I had done was losing the plot in any way.

Matt and I seem to share a lot of the same philosophies about tracking drums. These days it’s easy to use a lot of samples to get sounds and to sort performances out on the computer. Matt’s approach, as often as possible, is to use the drums themselves: work with the tuning and mic configuration, and dial in the room and the board to get the sound before making sure the performance is captured live. We may edit between takes and find the best moments, but those moments truly exist and aren’t manufactured. It might take a bit more time and be more labor-intensive, but it’s far more rewarding. Advertisement

MD: There’s an interesting pattern in the verses of “She Speaks the Language,” and it sounds like there are some rapid single bass drum doubles. How did you develop your bass drum technique?

Adam: A lot of the quick single bass drum stuff comes from our early days of playing fast hardcore punk. We’ve evolved over the years, but some of those chops stuck around and became a natural part of my playing. I’m self-taught, for better or for worse, so I developed a lot of my technique by watching other drummers or figuring out what works on my own. When I was fifteen or sixteen, I had a VHS tape of a Bad Religion show called Along the Way. The drummer, Pete Finestone, had a clear resonant head on his kick, and you could see the beater hitting the batter head. I remember squinting at the TV and studying what he was doing with his foot before running out to the garage to try to recreate it.

MD: If they were isolated, the grooves on “She Speaks the Language” could almost fit in a pop or hip-hop setting. Were there any influences or concepts you were thinking about with this song?

Adam: That’s a fun song to play. The kick, snare, and hi-hat half-time pattern locks in with the delayed guitar right at the top, and then halfway through the intro, percussive loops and a standard backbeat comes in. The part was designed to work with the loops, and the challenge is to play stiffly enough to avoid flamming with the loops but loose enough to give it a pocket. It’s busy, but I think it sounds pretty cool.

MD: You’ve been a member of AFI since the band’s beginnings in 1991. What does it take to have such a lasting career with one group?

Adam: I feel extremely lucky to still be doing this band twenty-five years in. I don’t know if there’s a recipe for longevity that applies across the board, because every band situation is different, and dynamics and personalities play a huge role in how bands function and in how long they last. For me there’s always been an overwhelming sense that playing music is what I’m supposed to be doing in life, and I’m lucky to do it, so I should take it seriously. I felt this when we were high school kids banging around in the garage, and I feel it today as we’re set to release our tenth full-length. I think the dedication we’ve had and the fulfillment I’ve felt every step of the way—from self-releasing EPs and playing basements to playing main stages at festivals—has helped us stay focused and soldier on. Advertisement

MD: What advice would you give to up-and-coming bands or drummers who want to pursue a career playing music?

Adam: Do it because you love it, and make sure you enjoy yourself every step of the way. If it’s not fun, what’s the point? I think it’s important to be proactive at every level and make your own opportunities instead of waiting for some “big break.”

Adam’s Setup

Drums: DW Collector Series

9×13 tom

14×16 floor tom

16×18 floor tom

18×24 bass drum

Snares: various

Cymbals: Zildjian

15″ K Light hi-hats

19″ K Dark Thin crash

20″ K Dark Thin crash>

22″ K Constantinople Bounce ride

24″ K Light ride

Sticks: Vater Power 5B wood tip

Photo by Drew Kirch