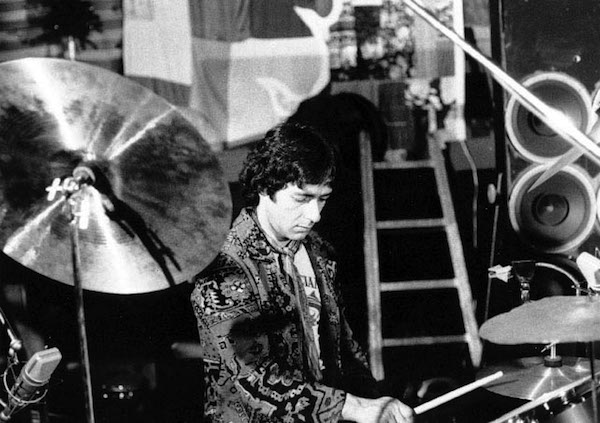

Jaki Liebezeit: Hero to a Generation of Thinking Alternative Groovers

by Ingo Baron

“The first time I heard Jaki Liebezeit’s playing with Can,” says Wilco drummer Glenn Kotche, “I was hooked. You can tell instantly that there was so much going on with his playing just under the surface. His super-solid feel is readily apparent, but the way he uses dynamics and ghosting to enhance the groove is masterful. He also changes things up ever so slightly to perfectly enhance everything else that’s happening with the music. Sometimes he’ll just add one little beat displacement or loosen his hi-hats for one hit. It’s little things like that—which keep things evolving over what might seem like a static beat—that I think a lot of drummers could learn from. I definitely have.”

Jaki Liebezeit is a true revolutionary, working against the grain of complex, mercurial progressive-rock drumming and formulating his own highly stylized groove-based approach with German “Krautrock” band Can throughout the 1970s. At the end of that decade, when nearly all of progressive rock’s most popular acts were unceremoniously washed off the front pages by the twin storms of punk and new wave, Can was one of the very few veteran bands whose credibilty remained intact. The group profoundly influenced next-generation art rock bands from PiL and Tortoise to Stereolab and Radiohead to the Red Hot Chili Peppers and the Flaming Lips, and still gets namedropped regularly as a prime source of sophisticated, soulful, barrier-pushing ideas. This is largely down to the playful yet trance-inducing approach Liebezeit takes on classic Can albums like Tago Mago, Ege Bamyassi, and Future Days, which feature such highly studied slabs of forward-thinking groovesmanship as “Halleluwah,” “Mushroom,” “Vitamin C,” and “Moonshake.”

It wasn’t always this way. “I came from jazz and played free jazz for two years,” says Liebezeit from his rehearsal studio in Cologne, Western Germany. “In the mid-’60s I was the first free jazz drummer in Germany. But I stopped that because, to my mind, I couldn’t develop any further in that genre. In free jazz you just weren’t allowed to play anything that was harmonically or rhythmically structured. It’s a paradox, but within free jazz there were too many limitations for me! After two years I couldn’t stand that anymore. Repetion or doubling something is a basic element in music. Advertisement

“With Can I was finally allowed to do what I wanted,” Jaki continues. “Repeating rhythms and grooves over and over again very consciously was a whole new thing at the time—even though this is an old idea: You find repetitive patterns in every culture of the world. In Europe during the ’60s this wasn’t understood at all. But the truth is simple: Without any repetition there is no groove.”

For Liebezeit, repetition need not equate to a lack of creativity; on the contrary, he took it as a challenge to make his beats as interesting as possible so as not to become monotonous. “For every piece I figured out a special rhythm or idea and repeated it all the way through,” he says. “Sometimes up to the stars! I consciously didn’t vary anything. Not too many people got that idea at the time. Many guys thought, This is really awful; you simply can’t come up with something. Later, when drum machines and looping became popular, everybody suddenly got it. This is daily business nowadays—though a machine cannot invent a rhythm, that’s for sure.”

Today Liebezeit follows the same philosophy he constructed more than thirty years ago, albeit perhaps more consciously than he did at first. “Nowadays I love to react to very strict rules that I formulate for myself,” he says. “First, I have to define ‘my rhythm’: What does it mean if I play in, say, 4/4? Nothing! You can play anything in that time signature. But now I define rules concerning time intervals that build specific bars, and I use different sets of volume levels or different colors of sound. Structure and rhythm stay the same—this is the rule I have to follow—but by changing these other basic elements, I can construct anything. Advertisement

“I didn’t know these rules early on,” Jaki continues. “I just had an intuition about it. But I started to really think about rhythms and systems, such as taking a four-beat rhythm but not dividing it into equal parts. Outside Europe, most cultures use an additive system, whereas in Europe you are using a dividing system. And these two systems are not compatible. In Europe and America you constantly think about notes. Then there are, especially in classical music, emphasized and non-emphasized parts, which are defined by the barline. But the problem is, there are no barlines in real life!

“For me, Can was a challenge to create some really new music; we wanted to sound unique. Most rock bands in Germany wanted to sound really English, so in England no one recognized them as German. Can was different. That’s why it was successful, especially in England. People hadn’t heard anything like that before—really ‘un-English.’ Can was as relentless and had as contrary an attitude as punk had some years later.”

Though Can tracks like “Spoon” represent the early use of drum machines, and Liebezeit has played in almost exclusively “electronic” musical environments for the past fifteen years, he says he has very little interest in electronic drums. “Today I play totally acoustic drums,” he insists. “I don’t find e-drums too exiting. By putting a microphone to a drum, it gets sort of ‘electronic’ imidiately. I need a natural relation between the attack and the resulting volume. E-drums are for dance bands! Advertisement

“But I do like to play to machines,” Liebezeit concedes. “That presents a lot of opportunities. With Can we used machines to keep the tempo—especially while using echoes and other effects. We didn’t use a click track, though, because that clearly was an unmusical element. Later on we would edit the tapes, and there would be no problems.”

A theme that runs through Liebezeit’s career is that of invention. “I’m a self-trained musician,” Jaki says, “and I still find out things today that you can’t read in books or learn in music schools. Most things I found out just by thinking about rhythms and how to execute them. It takes a long time before you can get rid of all your ballast and find ‘the real thing.’”

According to Liebezeit, today Can sells as many records as they did back in the day, and the drummer is still hard at work, perfecting his craft in a duo with the multi-instrumentalist Burnt Friedman. “Electronic music is the main aspect of that project,” he explains, “because it mainly focusses on computer-based things and my drumming. But the computer turned into a real instrument for us, which can be played ‘live.’ With that idea in mind, I needed a very special drumset, which I’ve been using since the mid-’90s. Advertisement

“I don’t play jazz or rock anymore, so I more or less said goodbye to the traditional technique. A ‘normal’ drumset with hi-hat, snare, bass drum, and toms really bores me. I wanted to simplify. Why should I use pedals? If a screw loosens on the hi-hat, most jazzers are completely lost. In rock, take away the cymbals or the snare wires, and the drummer is helpless. That’s a pitty! So I use a snare drum without any wires and three slightly modified toms. I also use a modified technique that comes from traditional drumming. I seldom use any cymbals; therefore I don’t need light or pointed sticks. So I use quite heavy sticks now to get the bass sound out of the drums. Though miking drums is always a problem, this has simplified the process. Basically I like to have just two drums. Everything else is an extension of that. Take a davul from Turkey: It has just two sides. I studied these drums for a long time and tried to translate these things onto my drumset.”

Fans of Jaki Liebezeit can still see him play today, though he rarely performs outside of Europe. “I still play concerts as they come,” he explains, “and I still try to improve my playing. I practice a lot, just like a sportsman. And I still work with my project Drums Off Chaos in Cologne and with some other projects spontaneoulsy.”

With all of Can’s original members, save for guitarist Michael Karoli, still alive and well, the inevitable question of a band reunion regularly comes up. “We didn’t separate from each other musically,” Jaki explains, “but rather took different directions. I don’t see a necessity to play together again. Besides, our records are still available.” One suspects they’ll remain that way for quite some time, providing open-minded musicians with food for thought for many years to come. Advertisement

This piece originally ran in the March 2011 issue of Modern Drummer magazine.