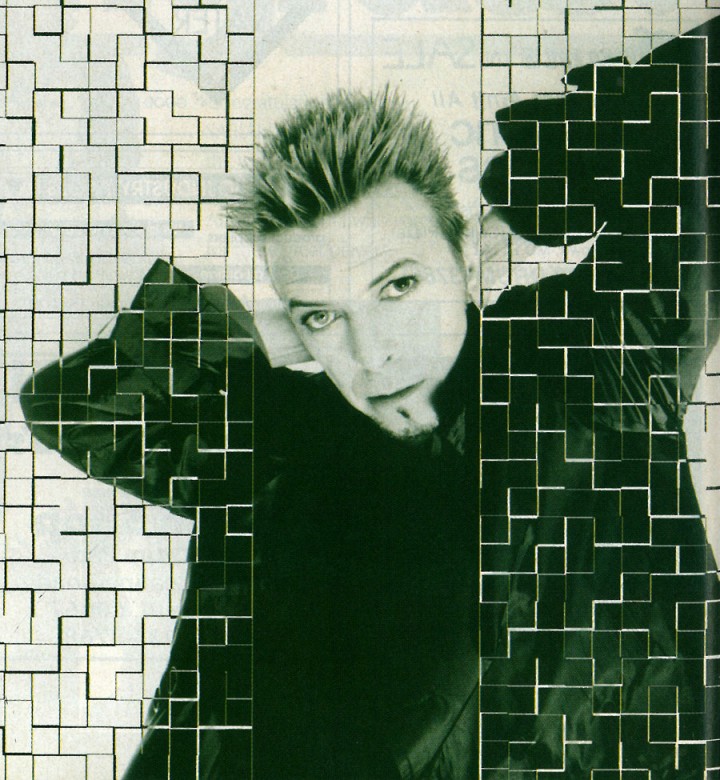

David Bowie: A Different View

by Adam Budofsky

The music world is quite a bit less bold today with the passing of David Bowie, the iconic artist who was as famous for his appetite for new musical ideas as he was for his ability to wholeheartedly inhabit whatever sonic world he created. One happy result of the singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and producer’s adventurous spirit is the treasure trove of wonderful drumming performances—and, even more importantly, drumming ideas—that his four-decades-deep recorded catalog contains. Bowie spoke to Modern Drummer in July of 1997, providing great insight into the many wonderful drummers who served him so well over the years. In honor of his passing, we present that article here in full.

By the time they reach fifty years of age, most musicians avoid the unfamiliar in all its shapes and guises. They’ve long since made their unique artistic statements; now it’s time to coast and “give the people what they want,” as Ray Davies of the Kinks would say.

During his half-century on Earth, David Bowie has made no secret that this is not his mind-set. With each new Bowie release, pop fans are reminded just how quickly most other artists lose touch with their muses: Sure, Bowie has had his share of artistic near-misses, but he’s certainly never forgotten rock ’n’ roll’s promise to shock, excite, mutate—elicit a reaction. Advertisement

Through periods of spacey folk/cabaret, riff-heavy glam, smooth soul, random Germanic avant-rock, or out jazz/metal, Bowie has made it clear to aspiring drummers that preparing for the first day of rehearsals means nothing less than opening your mind to every possibility.

This year has found Bowie bathed in a brighter spotlight than he’s enjoyed in quite some time. Some of the attention is due to his turning fifty, the star-studded birthday bash he threw for himself at Madison Square Garden to celebrate the event, and his highly publicized embracing of online artistic avenues. Mostly, though, it’s his new collection, Earthling, and its fractured drum-’n’-bass-driven slabs of futurist sound that have reset our sights on DB.

Appropriating, intensifying, and reconfiguring the hyper-speed drum parts of England’s latest club craze, Bowie throws the role of rhythm in modern music into full relief—and seriously tests the chops, smarts, and taste of new drummer Zachary Alford in the process. “What I really wanted to do,” Bowie explains, “was not so very dissimilar to what I did in the ’70s—and something I’ve repeatedly done—which is to take the technological and combine it with the organic. It was very important to me that we didn’t lose the feel of real musicianship working in conjunction with anything that was sampled or looped or worked out on the computer. Advertisement

“This record owes a debt to drum-’n’-bass in the use of rhythm,” Bowie offers. “But I don’t have much interest in the top information; what we are doing is a million light-years away from what, say, Goldie or any number of other drum-’n’-bass or purist artists would be doing. Groups like Storm Trooper are fantastic, but it’s not what we’re doing at all.”

Predictably, the recording process for Earthling wasn’t quite “cut live and keep what we can.” According to David, “I indicated to Zach the style and tempo of the piece of music; virtually, that’s all I gave him. He would take like half a day and work out loops of his own on the snare, and create patterns at 120 bpm that we would then speed up to the requisite 160. Then he would have that as a bedrock to play on top of. That loop would be fairly minimal—maybe four or eight bars maximum. And then over the top of that he would improvise on a real kit. So what you had was a great combination of an almost robotic, automaton approach to fundamental rhythm, with really free interpretive playing over the top of it. I think the best example of that on Earthling is a track called ‘Battle for Britain,’ where you really get a feeling for how Zach and the loops are interacting.”

Readers might recognize Alford from one of several high-profile situations the drummer has appeared in recently, like major tours with Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel’s Shades of Grey album and documentary, or the B-52’s’ popular “Love Shack” video. Bowie learned about the drummer through his previous timekeeper, Sterling Campbell, who played on his envelope-pushing last album, Outside. “Ironically,” Bowie explains, “Zach is Sterling’s best pal. Sterling got a great offer from Soul Asylum to become an integral part of the band, and quite rightly he said, ‘Look, guys, I’d love to do the [Outside] tour, but this is a real opportunity for me to join a group proper. But you might like this kid.’ That’s when he recommended Zach. Advertisement

“The moment he sat down,” Bowie continues, “I thought that Zach was absolutely great. He’s only a young guy, but he’s played hard and well over the last few years, and he’s got a pretty varied diet—everything from soul bands to hard rock. He’s kind of like the rest of us; he’s quite eclectic in his taste. He likes all kinds of music as long as it’s good. I think that’s what you would find with everybody in this band: There is nobody who is stuck in a particular place. Everybody is very open to new musical experiences and listening to anything that’s good or inventive or has new information. You’ve not got any closed ears in this band.”

Ironically, David Bowie’s constant and groundbreaking musical explorations sometimes overshadow his extensive abilities as a vocalist. (Drummer Joey Baron, in his July ’96 Modern Drummer feature, recalled being struck by the pure strength of Bowie’s voice.) With his style of music—and singing—potentially changing at the drop of a hat, how does that affect what Bowie expects and needs from a drummer? “The style of drumming will change from project to project,” Bowie agrees. “So it really is ridiculous to ask a hard rock drummer to get involved in something that is very soul-based, for instance. But what I look for in any drummer that I work with is a guy who knows how to support the vocals, but at the same time is quick enough to dash in with an inventive flurry if necessary to give the music a greater kaleidoscopic quality—which I feel is what Zach’s forte is. He just knows how to do both those things. He can be terribly supportive when you are going through the verse structure. But then, as soon as you finish that verse, he is capable of going along with [keyboardist] Mike Garson, who he rides off a lot—as well as [bassist] Gale Ann Dorsey, of course. He can start becoming very inventive in those parts where I’m not singing. And he listens to the music.

“Interestingly enough,” Bowie goes on, “Zach is also one of the few drummers who, when you do playbacks, doesn’t say, ‘Should my snare drum be louder?’ [laughs] Actually, that’s being unfair—it applies to all musicians. But the people in this band tend to have a good overview of the music, and it’s really satisfying to work with people like that. It’s understandable that musicians don’t want to feel left out in the cold, but it’s kind of frustrating when the only thing they’re ever listening to is their own instruments, and they don’t really understand that it’s supposed to be an integral part of an overall landscape. Luckily, because of the nature of the work that I do, it does tend to attract people who aren’t like that.” Advertisement

As Bowie suggests, the style of music he’s working on at any point dictates the type of drummer he likes to work with. Mick Woodmansey was the drummer many people heard when they were introduced to Bowie’s music through the string of early ’70s albums that made the singer a phenomenon on both sides of the Atlantic. The Man Who Sold the World, Hunky Dory, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, and Aladdin Sane revealed Bowie’s truly unique stage and studio persona through hits like “Changes,” “Ziggy Stardust,” “Suffragette City,” “The Jean Genie,” and “Panic in Detroit.” “Mick was a very fundamental drummer,” Bowie recalls. “I think he knew his strengths and weaknesses quite well. Mick never became overly ambitious. He was quite open to direction as well, and in a way sort of carried out what I wanted done much more than most of the other drummers I’ve worked with. His strengths definitely were in the area of British rock and British rhythm ’n’ blues. He understood the kind of drumming that one associates with the band Free, for instance. For most of those guys in that band, that was kind of the ultimate rock-god band for them. [laughs] So he’d really work hard at that style of drumming, which was fairly fundamental but had sort of a simplistic aggression to it.”

The next several Bowie albums represented a transitional period of sorts for the singer, and featured Aynsley Dunbar (Pinups, Diamond Dogs—“the loudest, hardest, baddest, most British of rock stars,” according to Bowie), Tony Newman (David Live), and Andy Newmark (Young Americans). Bowie’s next skinsman, though, Dennis Davis, would contribute to the series of releases that are considered by many to represent the artist’s peak: Station to Station, Low, Heroes, Stage, Lodger, and Scary Monsters. “Dennis was so open,” Bowie fondly recalls. “He was almost orgiastic in his approach to trying out new stuff. He’d say, ‘Yeah, let’s do that new shit, man.’ I told him about a Charlie Mingus gig that I saw where the drummer had polythene tubes that would go into the drums, and he would suck and blow to change the pressure as he played. Dennis was out the next day buying that stuff. Dennis is crazy, an absolute loony man, but he had a lot of his own thoughts on things, and he would throw us all kinds of curveballs.”

Bowie seems to take some sort of paternal pride in relating that Dennis Davis was in fact Sterling Campbell’s drum teacher—and likes to illustrate the relationship with a little anecdote. “This is very ‘Dennis’: Sterling Campbell used to go over to Dennis’s house to ask for lessons, and Dennis would say, ‘Ah…sure. You want to clean those windows?’ [laughs] Sterling looked after Dennis’s pad, and in return Dennis taught him. Isn’t that great? Dennis, of course, came to many of the gigs we did when Sterling was around, and then in turn, Sterling has always come to all the Zach gigs. And then all three of them have turned up on some occasions. They all get on very well with each other. So it’s lovely that I’ve got this kind of a real lineage between them, going back to 1976.” Advertisement

The mid-’80s proved to be a commercial zenith for David Bowie, even if the critics (and he, himself, in retrospect) weren’t all too thrilled with the more accessible if less challenging material of Let’s Dance, Tonight, and Never Let You Down. Still, drummers were treated to top-notch performances by players like Tony Thompson and Omar Hakim, the latter of whom David today refers to as “a guy I would have loved to tour with. Omar is a fascinating drummer, with impeccable timing. He’s always fresh in his approach.”

Opinions differ regarding Bowie’s next ‘band” project, Tin Machine, but it’s pretty clear that the experience pulled the singer out of a creative rut. “That was a bizarre project,” Bowie says, “but I’m really glad we did it. I mean, what [guitarist] Reeves Gabrels and I got out of it was a whole set of instructions about what we wanted and didn’t want to do [next].”

The drummer in Tin Machine was Hunt Sales, a journeyman player with credits ranging from big-band gigs, to Todd Rundgren, to Iggy Pop, whose watershed Lust for Life album Sales had played on and Bowie produced. Tin Machine was designed to be about playing—loud, improvisatory, metallic hunks of sound that gladly traded the potential of train wrecks for the chance of musical epiphanies. “Some nights it just blew me away,” Bowie recalls. “It was so adventurous and so brave. When it worked, it was unbeatable—some of the most explosive music that I’ve been involved in or even witnessed. But when it was bad, it was so unbelievably awful, you just wanted to have the earth open up and take you under. Hunt did some extraordinary things in that group, though. I always felt that he would have been more in tune with a big band setup; he plays like a big band drummer—his snare even faces outwards. The whole thing about him is that slouch and mood of the big band drummers. Advertisement

“Fortunately the world never really got to hear us at our worst,” Bowie says. “But then again, I think they probably never got to hear us at our best, either. The albums are almost an appendage to the whole thing. We were really a live experience. There is an album we put out called Oy Vay, Baby—which is Hunt Sales’ title, I might add—the whole Soupy Sales link. [Hunt and his brother Tony, the bassist in Tin Machine, are the sons of legendary comedian Soup Sales.] But the track ‘Heaven’s in Here’ gives some indication of what we were like when we were good.”

Following a couple more hit-and-miss solo albums, Bowie emerged in 1996 with Outside, an album deemed “difficult” and overambitious by some, but which nonetheless contained some startling material. Outside featured the work of Sterling Campbell, whom Bowie describes as “spontaneous and extremely inventive. Sterling plays a song differently every time; there are definite shades of his teacher, Dennis Davis.” Outside also featured the playing of Joey Baron, about whom Bowie proclaims, “Metronomes shake in fear, he’s so steady.”

Outside provided the blueprint in some ways for Earthling’s man-machine experiments. Bowie suggests that Zachary Alford’s ability to work with the electronics on the Outside tour and on Earthling has somewhat encouraged the whole band to grow into the situation together. “Zach has been such a substantial part of the way that we’ve worked over the last year and a half,” he says. “We’ve got the balance pretty good now between how much we should lean toward the organic side of things and how much we should have the fundamental, industrial sampling/looping quality. We know how to operate in that world very well now.” Advertisement

How long David Bowie chooses to inhabit this particular world is anyone’s guess. In the meantime, the music scene in general—and drummers in particular—should be glad that his artistic wanderlust has led Bowie—and us—down yet another path of exploration.