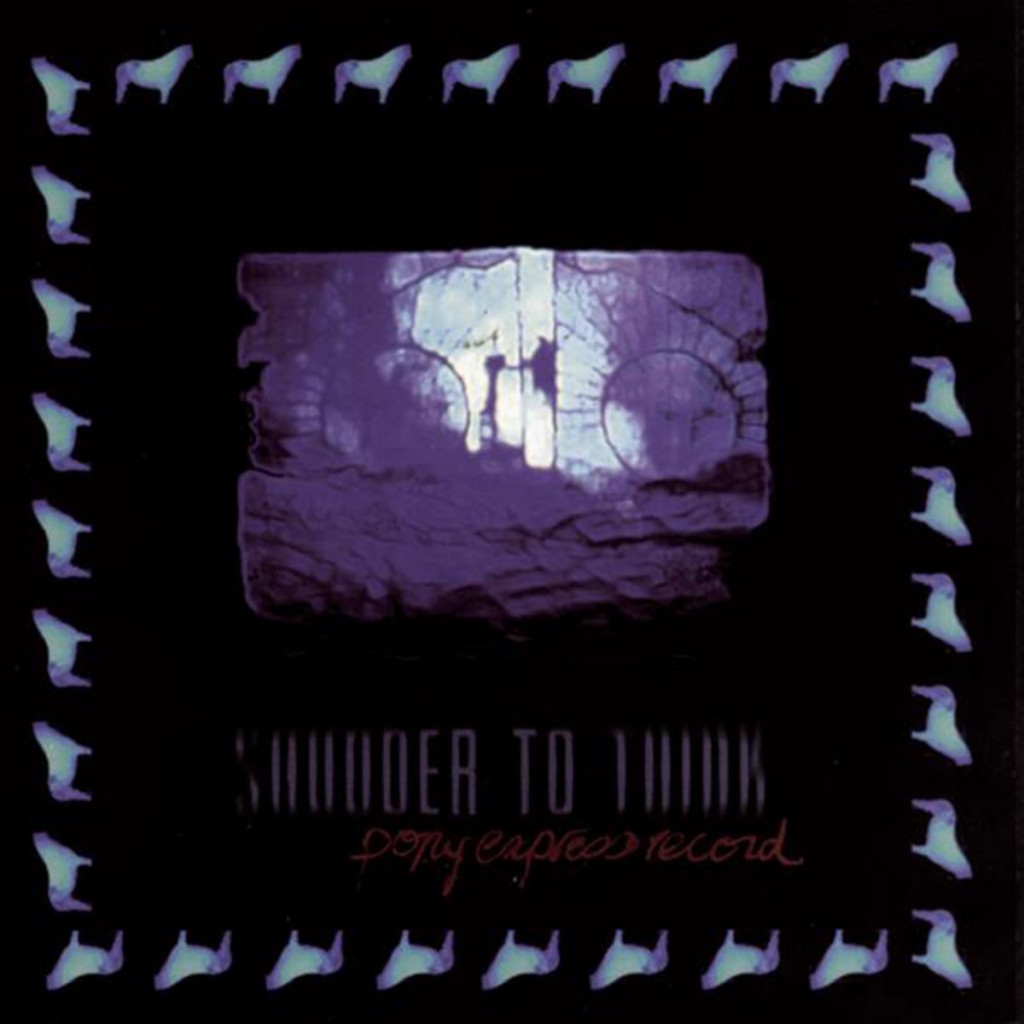

Encore: Adam Wade on Shudder to Think’s <em>Pony Express Record</em>

by David Jarnstrom

Though Adam Wade cut his teeth with seminal ’90s noise rockers Jawbox, he didn’t truly come into his own until joining fellow Beltway-based post-hardcore pioneers Shudder to Think. Manning the drumkit on the latter’s prog-pop masterpiece Pony Express Record—an under-sung treasure of the alt-rock epoch—Wade weathered Shudder’s stylistic schizophrenia and time-signature hopscotch to deliver a classic performance worthy of air-drum immortality.

In recognition of Pony Express Record’s twentieth anniversary, Wade spoke to Modern Drummer by phone from his home in Los Angeles, where the journeyman timekeeper settled following post-Shudder stints in Sweet 75 (Krist Novoselic’s other band) and emo-rock outfit the Jealous Sound. Now an audio engineer by day, Wade recently dusted off his sticks to play a rare Shudder reunion gig and to hatch his new band Terror Tuesday, which also includes ex-members of Volcano Suns and Lavender Diamond.

MD: Pony Express Record failed to crack the mainstream, but those who got it consider it one of the great cult records of the ’90s. How do you feel it’s held up after two decades?

Adam: I think it holds up extremely well, but I’m still floored that people continue to express their love and admiration for the album. It’s such an anomaly, you know? It’s a weird record; I still don’t quite get it to this day. I don’t think it was ahead of its time; I just think it’s out of time. It’s on another plane in its own little bubble. But that’s the great thing about Shudder To Think—apart from the hooks and the melodies, that is. There was always an element of mystery there. The music was like a puzzle. Advertisement

It’s also a great sounding record. It’s bombastic. The drums are just huge. They were recorded really well, which is a testament to [engineer] Steve Palmeri. And [mixer] Andy Wallace, Mr. Nevermind, did his thing—to the point where there’s the same shotgun reverb snare drum effect on “Hit Liquor” that’s on Nirvana’s “On a Plain.” I always got a kick out of that. I think if the record had been recorded lo-fi it might not have held up so well.

MD: In retrospect it’s crazy to think material this challenging was ever marketed for mass consumption. Was Sony/Epic [the major label that Shudder to Think signed to after being on hallowed indie Dischord ] pretty hands-off in terms of the band’s creative direction?

Adam: Yeah, they let us do whatever we wanted, which was amazing considering that record was heavily funded. We had a month of pre-production, and then we were in the studio for another month. Nobody does that anymore! Some of the songs weren’t fully written either. To be recording to two-inch tape while still writing in the studio—that in and of itself is a luxury. Advertisement

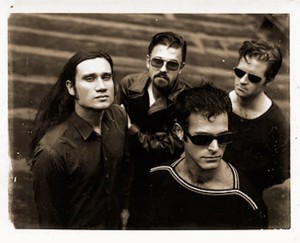

Shudder to Think in the early ’90s. From left: bassist Stuart Hill, guitarist Nathan Larson, singer Craig Wedren, drummer Adam Wade

But Epic didn’t really know what to do with us. The thing is, we weren’t like a typical rock band dealing with tropes—like, “Here’s the heavy part; here’s the funky part.” High up on our agenda it was like, “No matter what, we cannot sound like anybody else.” We didn’t want to be Fugazi or Soundgarden—though those influences were there.

MD: Your drumming on the first two Jawbox records—like Mike Russell’s on the first three Shudder to Think albums—is by no means easy, but it’s a cakewalk compared to the constant time signature switcheroo of Pony Express Record. Was it hard to wrap your head around these songs?

Adam: It was very hard. Get Your Goat [the record preceding Pony Express Record] was kind of the beginning of [singer/guitarist] Craig Wedren trying to basically deconstruct the guitar. He would invent these weird chords and turn them into big loops that would be in some crazy time signature. I can still remember the first time I heard “Hit Liquor.” Craig says, “I’ve got this song and it goes like this [mouths a meandering, jagged riff].” And I was like, “What the…fuck off!” [laughs] Advertisement

My gut reaction was to play as straightforward as I possibly could. I’d find the downbeats and accents and the little pockets for the kick drum. My mantra became, “The weirder Craig’s going to get with these riffs, the more ‘duh’ I’m going to play.”

MD: So you weren’t charting out time signatures or anything. You’d just find the “1” of these loops and follow the guitar line?

Adam: That’s pretty much it. I would find my “1” of the loop. That was the fun thing about these weird riffs—there was no real beginning or ending, so you’d kind of make one. And then the vocals would go on top of that, which would solidify things and give you a better road map. Then the four of us would finish it off, polish it up. I did a lot of arranging. Drummers tend to be good arrangers—that was certainly one of my roles.

MD: When making a major-label record, the drums are really put under the microscope, both in the studio and during pre-production. Did you find yourself becoming a better player as you went through that painstaking process? Advertisement

Adam: When you’re in the moment of doing that work, not necessarily. I experienced the benefits afterwards, especially from working with producer Ted Nicely [Fugazi, Jawbox]. Ted kicked my ass. He really put me through the wringer. That’s when I first started getting grey hairs. [laughs] While we were tracking drums, Ted had a device in the control room called a “Russian Dragon.” It’s a box and on it are seventeen LED lights—eight on the left, eight on the right, one dead center—and he patched the kick drum and the click track through this. The click track light is always dead center, but the kick drum light would move to the left or right depending on how behind or ahead of the click you were. We’d do a take and Ted would watch the machine and go, “You’re rushing a bit there, you’re dragging a bit there—do it again.” And maybe if you hit one of the far outside lights it was audible to a normal person. We’re talking milliseconds here. But Ted demanded perfection.

MD: That’s interesting, because it feels like you’re comfortably behind the beat most of time. It’s such a relaxed overall tempo for a rock record—it’s not stiff in the least.

Adam: Well, there’s a lot of space on that record, which reminds me of another Ted tip I keep with me to this day: A lot of young drummers, especially in punk rock, start a measure with a couple of 8th notes on the kick: “Boom, boom, bap!” Ted was always like, “I want you to go: ‘Boom, bap!’ Just play a quarter note on the 1.” This really helped create that space you hear on the album. That and there’s not a ton of big fills. There’s no real spot you can point to and say, “Look at that crazy whack-a-doodle drum thing.” The music just doesn’t call for it. It’s a spacious, complex record that didn’t need to be overcomplicated with more drums.

MD: Any particularly challenging songs in regards to drum tracking?

Adam: “Sweet Year Old” was really tough. When we went in to the studio, I didn’t have my head wrapped around it much as the other songs, so we experimented with different approaches and accents and fills. It took couple days, but I think it turned out great. I love that little double-stroke roll into the second chorus—that was totally spontaneous, but it fit. That’s become one of my favorite songs on the record. It’s got a total Led Zeppelin vibe to it. Advertisement

MD: “Own Me” has a Zeppelin feel as well, with that bluesy, 12/8 “Since I’ve Been Loving You” kind of beat.

Adam: Yeah, there’s a pretty blatant “Dazed and Confused” reference in that one as well. The choruses of “Sweet Year Old” have a “No Quarter” feel to me. Maybe not as funky, but kind of dark and weird like that.

MD: Near the end of the album you do a really unusual, deconstructed interpretation of Atlanta Rhythm Section’s ’70s hit “So Into You.” It’s super powerful—perhaps even more so because it’s the only song on Pony Express Record that’s entirely in 4/4 time.

Adam: Yeah, but it’s got all those kooky breaks with guitar feedback and stuff. [laughs] That sound is sort of like Shudder to Think meets Jane’s Addiction meets [D.C. hardcore band] Rites of Spring.” “So Into You” was a staple of the band’s live set even before I joined. It was a nice, big rock song we could call on when we were playing bigger rooms with bands like Foo Fighters or Smashing Pumpkins. For a few minutes we could just kind of rock out and not have to be counting in our heads. Although we did get to the point where we could just play the Pony Express Record tracks live without really thinking too much. It was such an amazing feeling to take all those crazy songs and just whip ’em every night. Advertisement

MD: You parted ways with Shudder to Think during the making of the follow-up to Pony Express Record, 50,000 B.C. Were you unhappy with more accessible direction in which the band was moving?

Adam: The band was in a bad place. I was personally in a bad place. Maybe I wasn’t playing that well—I don’t know. It’s funny, I remember telling Craig after the fact that I thought we were on the verge of making a really incredible, breakthrough record—and then Radiohead’s OK Computer came out. And I was like, “Oh, well, they did it.” [laughs] They made that first truly amazing, alt-rock/prog-pop record that really connected with everyone, you know? But yeah, I always wanted Shudder to stay weird and continue our mantra of “Let’s not sound like anything else.” If the four of us went in to make another record, I bet we could do it again.

MD: The Pony Express Record lineup reunited to perform for [Washington D.C. venue] the Black Cat’s twentieth anniversary last year. Is there any more activity planned for the future?

Adam: After we did that show, Craig threw it out there, like, “Hey, guys, want to do another record”? But logistically it’d be tough. Craig and I both live in Los Angeles, but Nathan [Larson, guitarist] lives in New York. He’s married to Nina Persson of the Cardigans, and she just released a solo record, so he’s off playing guitar on her world tour. [Bassist] Stuart Hill lives in North Carolina and came out of retirement to do the Black Cat show, but he doesn’t really play anymore—though you’d never know it from our rehearsals; he’s a machine. So I don’t know what’s going to happen in the future. But we certainly had a lot of fun playing together again, and the door was left open for more, should we choose to pursue it.

For more on Adam Wade and Pony Express Record, get the October 2014 issue of Modern Drummer magazine.