Billy Higgins: The Shape of Jazz

Billy Higgins, who would come to play on more than five hundred albums, including three of the biggest jazz crossover hits of the 1960s (Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man,” Lee Morgan’s “The Sidewinder,” and Eddie Harris’s “Freedom Jazz Dance”), was born in 1936 and grew up in Los Angeles. He began playing drums at a very early age, influenced first and foremost by Kenny Clarke but also by non-drummers like pianist Art Tatum and saxophonist Charlie Parker. In an October 2001 Style & Analysis piece in MD, the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra’s John Riley wrote that in terms of drumming inspirations, “Billy dug the melodiousness of Max Roach and Philly Joe Jones, Art Blakey’s groove, Elvin Jones’s comping, Ed Blackwell’s groove orchestration, and Roy Haynes’ individualist approach.”

Although Higgins, who died on May 3, 2001, after a battle with liver disease, made his name on the jazz scene, he came up on the West Coast playing in R&B bands and did an early stint backing Bo Diddley. His first real exposure in jazz came in the late ’50s, when he began performing and recording with saxophonist Ornette Coleman. A highlight of this collaboration was Coleman’s 1959 album The Shape of Jazz to Come, which truly lived up to its name in terms of forecasting some of the more avant-garde jazz releases to follow. With considerable thanks to Higgins, the album is still rather accessible and contains subtle dynamics and sweet brushwork.

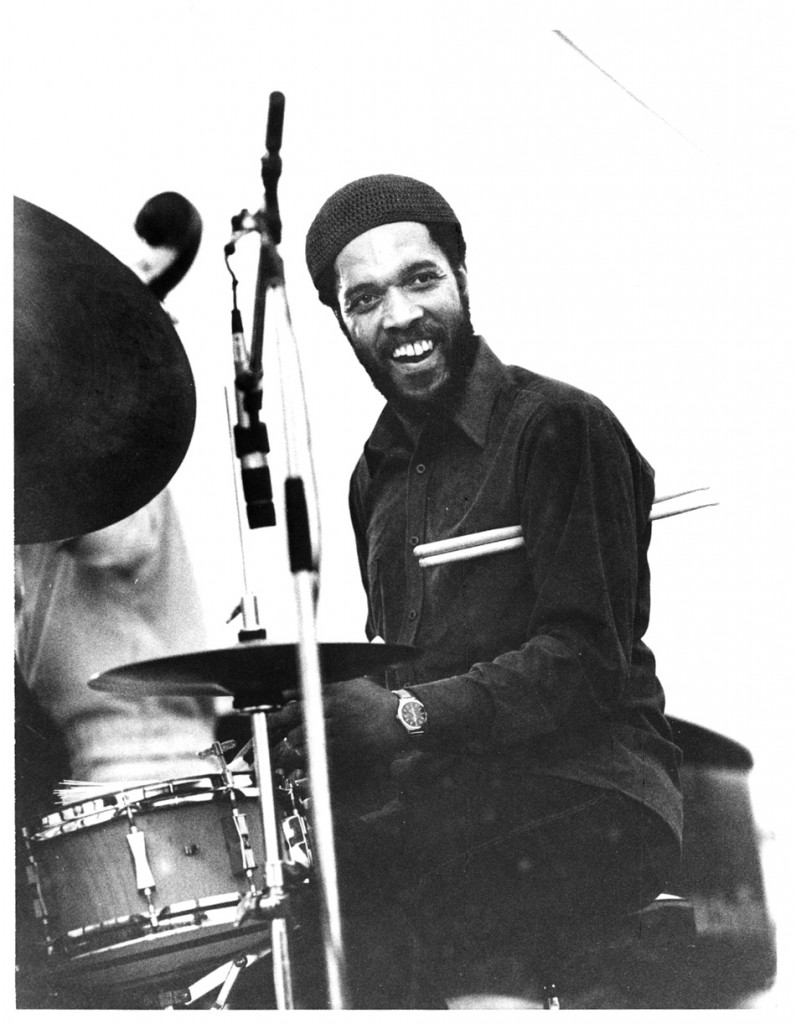

Higgins, who was known for his warm smile and happy demeanor, went on to play with the jazz greats Thelonious Monk, Dexter Gordon, John Coltrane, and Sonny Rollins, along with a younger generation of jazzers, including Herbie Hancock, Lee Morgan, Eddie Harris, and Hank Mobley. “Billy was a facilitator, not a dominator,” Riley wrote. “He would enhance the direction the music ‘wanted’ to go in rather than impose his own will on the composition. You can hear that Billy was a master at creating a good feeling in the rhythm section. Dynamically, he used the entire spectrum—but with great restraint. His comping and overall flow were very precise but very legato.” Advertisement

Talking about the stage in his February 1992 MD feature, Higgins said, “That’s where you learn. You learn to be in context with the music and interpret. You make your mistakes and you learn. Most of the drummers that are working are people who know how to make the other instruments get their sound. Kenny Clarke was a master at that. It sounds like he was doing very little, and he was, but what he implied made all the instruments get their sound. Philly Joe, Elvin—as strong as they played, they still bring out the essence of what the other musicians are playing. Roy Haynes, Max, Art Blakey—none of them played the same. You try to add your part, but the idea is to be part of the music and make it one. That’s the whole concept for me.”