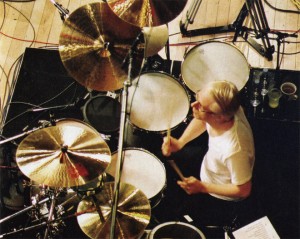

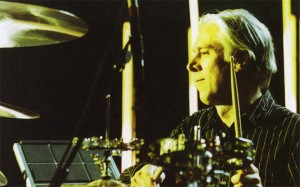

Back Through The Stack: Bill Rieflin

by Jon Wurster

“Honestly, I don’t remember, sorry to say,” replies R.E.M. drummer Bill Rieflin when asked what it felt like the first time he counted off the band’s smash hit “Losing My Religion” before a paying audience. “On those early gigs I was just trying to hold on and not play the songs at twice the performance tempi.” Heck, you’d be a little nervous too if faced with the prospect of filling the shoes of a founding member of one of modern rock’s most celebrated bands.

In truth, it probably seemed a little odd to some when word came in early 2003 that Rieflin would be taking over drumming duties for R.E.M. (Original drummer Bill Berry left the band in 1997 and was replaced by Joey Waronker.) Odd, because up until that time, Rieflin was known primarily for supplying the pounding, jackhammer rhythms for such industrial music heavyweights as Ministry, Revolting Cocks, and Pigface. While it’s true that the aggressive stomp of Ministry’s “Stigmata” is a hundred eighty degrees away from the folky melodicism of the aforementioned “Losing My Religion,” those who had followed Rieflin’s moves closely no doubt saw this latest endeavor as just another surprising twist in a very eventful and unpredictable career. One listen to his tasteful, temperate drumming on R.E.M.’s new album, Around The Sun, proves without a doubt that Rieflin is no one trick pony.

The Seattle native began his professional musical journey as a teenager in the mid to late ’70s as a member of two seminal bands, the Telepaths and the Blackouts. The latter, a hard-hitting post-punk outfit that relied heavily on Rieflin’s hypnotic, odd-time rhythmic pulse, would go on to release a handful of recordings, including 1983’s Lost Souls, which was produced by Al Jourgensen, frontman for the then synth pop–inclined Ministry. Advertisement

The relationship with Jourgensen would bear unexpected fruit three years later, when, after disbanding the Blackouts, Rieflin, keyboardist Roland Barker, and bassist Paul Barker joined a revamped, much heavier-sounding Ministry. Rieflin remained an integral part of the Ministry camp for the following eight years, playing on such genre-defining records as Land of Rape and Honey and Psalm 69, and participating in many of the often hilariously named and sonically aggressive projects released through Chicago’s Wax Trax! record label.

Internal tensions eventually took their toll, and in 1994 Rieflin left Ministry in an effort to find peace of mind and seek out new musical horizons. Now a free agent, Rieflin found his services much in demand as he landed recording work with a wide array of artists, including Peter Murphy, Robert Fripp, Swans, Krist Novoselic, Chris Connelly, Nine Inch Nails, Chris Cornell, and KMFDM.

It’s important to note that Rieflin’s role in many of these projects was not necessarily that of drummer. A true multi-instrumentalist, he could often be found contributing whatever the session required, be it guitar, keyboards, bass, or acting as producer. Advertisement

The final year of the twentieth century was to be a watershed for Rieflin; it saw the release of his first solo album, Birth of a Giant, and perhaps more crucially, the forging of a connection that would lead to his being asked to play with one of the most successful and influential bands of the last two decades.

When speaking with Bill Rieflin, one thing quickly becomes clear: He really thinks about music—not in a rigid, studious way, but in a manner that’s natural, almost spiritual. Rieflin’s comments on the importance of “being in the now” and remaining present at all times are at once obvious and revelatory. They help paint a picture of an artist possessing a deep desire to get inside the music and explore its effects on composer, performer, and listener.

MD: You’re a great example of a drummer who has succeeded in some very different genres: From playing with Ministry and Nine Inch Nails to your recent work with the Minus Five and R.E.M. How important do you think it is for a drummer to be versed in different styles? Advertisement

Bill: If someone is only interested in the color orange, then learning how to do orange really well, by focusing on orange, will serve that particular interest or need. However, it’s not often understood—particularly by young, eager, often impatient players—that learning red, blue, and yellow can help you do orange much better. This might not have as much to do with different genres and styles as much as having a good solid footing in the basics needed for good technique. Good technique allows flexibility.

MD: Speaking of the basics, did you have much formal training or participate in traditional school bands?

Bill: I began life as an ardent music listener. The more I consider it, the more I think that being a music listener is perhaps the most important feature of my musical life. I clearly remember being asked by my mother, while she was on the phone, if I wanted to take piano lessons. I said yes, though not automatically. My impression, thirty-seven years later, is that I needed to decide then and there. I had no sense of this being a major life decision, but it surely was. I mention this to underscore the idea that while being a music lover, I had no early ambitions to play, certainly no one instrument specifically. It was only because my mother knew I loved music that she thought I might want to play piano. Lessons continued for ten years, not always happily.

I had very limited drumming instruction. My mother once coerced me into taking lessons from a fife & drum teacher. That was short-lived. I did not play in the school band. It was all way too square for me. It’s not that I had no interest; I was openly antagonistic toward anything I thought of as “normal.” Advertisement

MD: Do you have any regrets about not taking lessons, or do you think that helped you forge your own style and sound?

Bill: It’s too late to regret it, but if I could go back in time and talk to my younger self, I would absolutely demand that he take lessons. It’s so important just to learn the basics: How to hold a stick…how to use your body efficiently…how to sit behind a drumkit…where your feet are meant to fall on the pedal…how to move from your hips and your ankles and toes…sitting and posture…balance…all that stuff. It would have made me such a better player.

MD: Who were some of the artists that got you excited about music and inspired you during those formative years?

Bill: Like most every young person growing up in the ’60s, the Beatles were everything. Anything that anyone has ever said or written about the magic and mystery and the excitement and awesomeness of the Beatles goes for me too.

My parents, like most other parents of that time, had a pretty good collection of show-tune records: Lerner & Lowe, Rogers & Hammerstein, etc. My favorite was Camelot. I listened to pop radio of the day; the Doors and Credence easily come to mind. In 1972, I was loaned [David Bowie’s] The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars. I fell in love with that record. I bought his Pin-Ups album the week it was released. Woody Woodmansy had been replaced on drums by Aynsley Dunbar by then, and someone asked me which drummer I liked more. It was the first time I had been asked to discern between different players. After serious consideration, I had decided that Aynsley was a more interesting, exciting, musical, and dynamic player. I’ve loved his playing ever since, particularly on that record. Advertisement

MD: In addition to drums, you play guitar, bass, and keyboards. How do you think this has benefited you?

Bill: It’s been extremely important and useful to me to able to play melodic instruments, if only for variety’s sake. It allows me a fuller understanding of the music I’m involved with. I also find it quite useful to be able to communicate with musicians in terms of the instruments they play. Conversely, I’ve worked with some non-drummers who could benefit from a few years of drumming experience. In 1989 I took some guitar lessons through [the Robert Fripp-founded school] Guitar Craft, and I really started getting into doing things “right,” as it were.

MD: Guitar Craft teaches a very specific way of holding and playing the guitar….

Bill: Well, it’s a very natural way of doing it. It’s the same as drums: The instrument comes to the body, so there is a natural way for the body to be most comfortable. I started to apply some of these ideas and principals to my drumming. And in 1992, when I was preparing for a tour with Ministry, all of a sudden I came to the conclusion that I didn’t know how to get better. I had gone as far as I could on my own, and I recognized that. There’s a drum school in town—Seattle Drum School—and I called them up and said I wanted lessons.

MD: For how long?

Bill: About three or four months. It was mostly working on hand stuff, not kit stuff.

MD: I understand you also took some instruction from [legendary Santana drummer/percussionist] Michael Shrieve recently.

Bill: I ran into Michael here in Seattle and said, “Come and show me some things.” He asked, “What do you want to learn”? I said, “Show me something I don’t know how to do”…which is a lot of stuff. So we sat for a few hours in my room and played through some things, and it was challenging and fun. The first thing we did together was play a really slow groove and focus on breathing. Advertisement

I ran into Matt Chamberlain at a party once and asked him, “What would you say is the most important thing in playing”? I don’t think he even took a beat, and he said, “Breathing.” He was the first guy who ever said that to me. And I thought, “Aaah, I like that; no wonder you’re so dang good.”

MD: Breathing is obviously very important. How does breathing relate particularly to drumming?

Bill: Well, your body will of course breathe by itself. But if you were to just sit and focus on your breathing, it gets a lot weirder, because you find that you’re involved with your breathing. For me, I find the most challenging thing is to just sit and notice the breathing without getting involved in it. To actually do something like that while playing drums sounds like a monumental feat.

MD: On a similar subject, I read an interview where you spoke about how essential it is to be “in the now” of it all. Could you elaborate on that?

Bill: The other night we were in Vancouver. It was a really fantastic show and I noticed that something would happen on the side of the stage, and I’d be distracted. I’d look over there and think to myself, “I don’t want my attention to be there; I want to be in the performance.” If I can put myself in my body and feel everything as it’s happening, that really helps put me back into the moment. So, as far as being “in the now” and being present, I return to the physical sensation and that helps me a lot. It’s very practical, because if you’re onstage and you’re just kind of going to go to sleep and something happens that you’re not prepared for, then you’ve lost it; the moment’s gone and you’ve missed out. Being “alive” during a performance is incredibly important. Advertisement

MD: In the late ’80s and early ’90s you were heavily involved with the likes of Ministry and Pigface. There seems to have been a real “collective” vibe to these bands, with nobody tied down to a specific role. You played drums or programmed on some tracks, and played guitar and keyboards on others. How did those projects come about, and how was it decided who would play what?

Bill: Everything happened in the studio. There was very little pre-production. We would go to the studio and start making records. Different combinations of people would have their own band names, and Al was always thinking up different projects for various combinations of people. The general rules of the game were that if you were around during recording, you were a part of the project. I never lived in Chicago, so I wasn’t always around.

One of the things that made work difficult for me is that the sessions were often chemically fueled. Being the straightest man in show biz, this left me at a disadvantage energy-wise and stamina-wise. I found no joy spending days on end in the studio, the options for participation becoming less as the sessions dragged on. The initial creative spark was often taken over by a megalomaniacal haze. Advertisement

MD: What do you think you learned drum-wise from those projects?

Bill:Mostly precision, consistency, endurance, and metronomic playing. I also learned that those early Simmons pads will ruin your elbow. One result of existing in the studio is that roles can be more fluid. The drummer in a live band needs to be the drummer. But if it’s all on tape, there is more flexibility and opportunities to do other things.

MD: There are reports that relations between you and Jourgensen were straining by the time of 1995’s Filth Pig. Did you already have a plan for where you were going next as your time in Ministry was coming to an end?

Bill: In the end, there was no reason to be in Ministry. Relationships were indeed strained, the music was of zero interest to me, and Jourgensen balked at paying me what I asked for. When I started playing with Ministry in ’86 it was all very computer, synthesizer, and noise based. Those records were pretty interesting for that time, and we had a lot of fun doing them. And then Al got more interested in guitar rock music like on [1992’s] Psalm 69. I’m just not interested in that metal guitar rock; it bores the crap out of me. I have been known to say, with great pride, that my last act in Ministry was to refuse to play on their version of Dylan’s “Lay Lady Lay,” which appeared on Filth Pig. Advertisement

When I left Ministry, I didn’t have a plan per se. My first concern was getting the hell out of there. My second concern was, “Well, what now”? Until that time, I had always been in a band. And bands tend to be fairly insular organizations. Now I was free-floating. I needed to re-examine what I do, and what I wanted to do. Of course, there is always the question of how to pay the rent. Fortunately, work came knocking at my door. The first week after leaving Ministry, I was in L.A. recording with my friends Chris Bruce [Waterboys, Seal] and Wendy & Lisa [Prince & the Revolution]. I quickly decided that variety of experience was something I wanted and needed.

MD: You were very much living a freelance existence at that time. What were some of the plusses and minuses of not being tied down to one specific endeavor?

Bill: One of the good parts was participating in a huge variety of work with a lot of people and doing things that I wouldn’t normally do. I gave myself a lot of experiences that I missed out on being in a very specialized band. The downside of course was being essentially an unknown guy, without an agent or manager. I never knew where the money was going to come from, and I never knew when I’d work again. I never starved, but it did give me a little stress.

MD: You recorded your solo album, [1999’s] Birth of a Giant, during that time. Was that something that had been gestating for a while?

Bill: There were a number of ideas bubbling in me that I no longer had a reasonable excuse to ignore. And I had the time to work on them. The “solo record” can be an iffy thing, often born from egotism, boredom, or in some cases, necessity. I was fortunate enough to rope in a few talented people to lend a hand, such as Robert Fripp and Chris Connelly. I think it’s a generally successful record and I’m sorry to report that I’ve got another one up my sleeve. Advertisement

MD: Now we’re closing in on your entrance into the world of R.E.M. How did that come about?

Bill: While trying to drum up some interest [laughs] in Birth of a Giant, the publicist I was working with suggested I meet Scott McCaughey [leader of the Seattle-based Minus Five and R.E.M. tour multi-instrumentalist]. Though I had known of Scott for years and had sort of crossed paths here and there, we’d never formally met. Sometime in ’99 he asked if I wanted to play an upcoming Minus Five show and I said yes. The bassist of the Minus Five is Peter Buck. Peter, as most will know, is the guitarist for R.E.M.

When R.E.M. was preparing to begin work on what was to become Around the Sun, I was asked if I wanted to do a few weeks of recording. A few weeks became a few more weeks. Eventually I was asked to do the European tour, then the U.S. tour. Then I guess they just got used to me hanging around. Perhaps at that point it was too much trouble to get someone else.

When I first began recording with R.E.M. in Vancouver, Scott had booked a Minus Five gig at a place called Richards on Richards in December of 2002. R.E.M. played three songs with me on drums that night. According to [R.E.M. bassist Mike] Mills, that was when he new that he’d like to play with me, that we could have fun playing together. Advertisement

MD: The Wax Trax! scene seems somewhat removed from R.E.M.’s. Were you aware of what R.E.M. was doing during the ’80s and ’90s?

Bill: It’s probably fair to say that though aware of R.E.M., I didn’t know their records. I knew pretty much what your average radio-listening, MTV-watching American knew about them. “Losing My Religion” was the first time I stopped to listen; a lot of it had to do with the video.

MD: Do you think they found it refreshing that you didn’t have that much familiarization with their oeuvre, that you weren’t going to be phased by “the legend,” so to speak?

Bill: I know what you mean, but I don’t know if that has benefited me in any way particularly. If anything it made it harder for me because I had to learn all those damn songs. [laughs]

MD: You’ve stated elsewhere that you really immersed yourself in Bill Berry’s drumming when you began playing with R.E.M.

Bill: When I was asked to do the tour, and because it was a “greatest hits” tour, I decided early on that I would do my best to play those songs as Bill Berry would. This meant not only learning the drum parts more or less verbatim, but I had to learn his feel. After all, a drummer’s feel largely determines how the music feels overall. And R.E.M. is R.E.M. in large part because of Bill’s feel; that’s one of the reasons the music is so well loved.

I can’t say if it was an easy thing to do, and I’m not really in a position to judge how successful I have been. What I did was listen to those songs night and day in order to find what made Bill tick. I suppose it’s something like an FBI profiler hunting down a serial murderer; you want to get into their skin, to discover what they’re all about. A person’s feel comes out of who they are. Once you find the key, the rest falls into place; you become familiar with the choices they make. Eventually I found something I could work with. After that things became easier. (continue reading on next page) Advertisement

MD: How is playing in R.E.M. different from other situations in which you’ve been involved?

Bill: R.E.M. can be seen as a system of various playing styles, feels, and approaches. With only a few people, things quickly become complex. Listening is the key—as it always is—which allows any musician to respond. The thing I’m constantly reminded of is that there is absolutely no sleeping when playing with R.E.M. You never know what will happen next. R.E.M. in one way has been one of the hardest things I’ve had to do. They have a very unique sense of themselves and how they play and how they play together. I don’t think that any drummer can just step in and expect it to work off the bat. I’ve worked through a couple different strategies—how to play and pull everything together so it sounds cohesive, so it sounds like music.

MD: I’m curious as to how the songs on Around the Sun were presented to you. Were they in semi-realized demo form, or were they just sketches that you, Mike, and Peter built from?

Bill: Some were in semi-realized demo form, some in fully realized demo form, some in the form of “Let’s try this and see what happens.” Michael Stipe would often sing during tracking to help with the overall feeling of the performance.

MD: Would Peter and Mike show you ideas they’d like you to try, or were you free to come up with your own parts?

Bill: It all depends. Sometimes, someone will want to hear something specific, sometimes we’ll just begin playing and see what happens. Sometimes I’ll set out to do something “interesting” or different; sometimes I just do my best to keep out of the way. Like every good musical group, the best idea wins, regardless of who has it. Advertisement

MD: There’s an understated sound and vibe to Around the Sun. On songs like “Make it All Ok” and “I Wanted to be Wrong,” did you ever find yourself having to pull back, for example, scaling back fills?

Bill: “Make it All Ok” was a difficult one. It went through a few different arrangements and keys, and lots of takes. I remember that on the CD take, I was fairly frustrated and slamming away, albeit slowly and with restraint. A few earlier takes might have had better drum stuff, but the finished take was best overall. “I Wanted to be Wrong” was recorded live with guitar, bass, vocals, and tambourine. The drums in the bridge were an overdub. I love that track. It’s the sound of musicians really listening. I have no problem whatsoever playing very simply. I often prefer it. And if it’s good for the track, how or why can anyone complain? For some time now, my playing and approach to drumming has been in the “simplify, simplify, simplify” area.

MD: When faced with doing multiple re-takes of a song, have you ever just had to say, “Y’know, that’s the best I can do”?

Bill: That has happened before. I can’t remember what session it was for, but it was a 6/8 feel and for some reason I just wasn’t getting it. It was played to a sequenced thing and I was feeling it a little differently than the computer was, and for some reason I just couldn’t relax into it. I just said, “Look, when do you want to stop, [laughs] because this is the best I can do. I’m really sorry to say this, but I don’t think I can play this any better.” It’s kind of a terrible thing to admit, but it’s kind of a practical thing to admit. Not to toot my own horn, but I think that’s a good quality in a musician—to be able to say, “I can’t do this.” Advertisement

MD: This leads to the next question, and a hotly debated topic: How do you feel about the widespread use of computer-based recording programs like Pro Tools? While they can be of great help, they also seem to have reduced the need for drummers to be able to actually nail a complete take.

Bill: I’m sure you’ve heard the one about the Pro Tools engineer calling to a band after a take: “That was really awful, guys…. C’mon in!” The performance question affects not only drummers. That different performances can be easily assembled without an editing block, razors, and tape I have no problem with. That someone needs to spend a week moving around drum and guitar waveforms because someone can’t play is another thing.

What concerns me more is something I’ve referred to as the “universal feel,” a euphemism for that ubiquitous, metronomic no-feel that seems to infect a majority of contemporary popular recordings. I have no beef with Pro Tools and digital recording in general. It’s allowed me to have a 64-track recording studio in my home. Ultimately, as always, it’s down to the quality of ideas within the operator. Advertisement

MD: You’ve done a good amount of producing but also a lot of sessions over the years. How do you approach a session on which you’ve been hired only to drum?

Bill: If I’m hired as a drummer I sometimes have to remind myself why I’m there. My aim is to do what is asked of me. Sometimes what is asked of me is to do anything I want. Being open to input is essential. I’m not paid to force my point of view on a recording.

MD: Your recent work with R.E.M., the Minus Five, Ken Stringfellow, and others has shown the world another side of your playing. But was there ever a time previous to this when you felt like you were in danger of becoming known as “Bill Rieflin, industrial drummer”?

Bill: If those were the kinds of records I made during a certain period, it’s not unreasonable that some would think of me as that guy. There are those who still think of me as an “industrial drummer,” whatever that means. If anything, I find it a bit embarrassing. Dealing with the expectations of others is always a problem. When those expectations are trapped somewhere in history it’s even worse. Advertisement

MD: Can you think of one specific record that you’ve played on that you feel is most representative of “the Bill Rieflin sound”?

Bill: No, although I do have favorite records that I’ve played on. Chris Connelly’s Shipwreck is a good record. One of the best tracks I’ve ever played is on a [former Screaming Trees vocalist] Mark Lanegan record called Field Songs. There weren’t any vocals on it, and it took like an hour to do it. The track already existed, so I was just playing drums on top. I listened to the record months later, when it came out. The one song I played on was the first song on the record, but I didn’t remember it because we just went through it in an hour. All I could think to myself was, “Whoever played on this song, Mark should have gotten to play on the whole record, because this guy is really great.” [laughs] Then at the end of the song I went, “Wait a minute, that’s me!” I was really shocked, pleasantly surprised, and extremely hopeful that I had found something that I played on that I really liked. I don’t know about other people when they hear themselves play, but I hate my playing. [laughs] I know that sounds funny.

MD: Not liking one’s own playing seems to be a complaint of a lot of great musicians.

Bill: I went to an Elvin Jones workshop once and someone asked him if he ever listened to his own records. And his response was, “Only if I want to hear all the mistakes or if I want to hear bad playing.” Right, I only listen to A Love Supreme when I want to hear crappy playing. [laughs]

MD: You’re just too close to it, I guess.

Bill: Maybe it’s reverse egotism or egotism turned on its ear. We’re all egotistical bastards. [laughs]

MD: Earlier you mentioned giving advice to your younger self. Knowing what you know now, what advice would you give to a young drummer just starting out today?

Bill: It’s music. Listen. Then, find an instructor who will guide you through the fundamental principals necessary to becoming an excellent musician and player. Have fun. Wear earplugs.

|

|

|||

|

||||