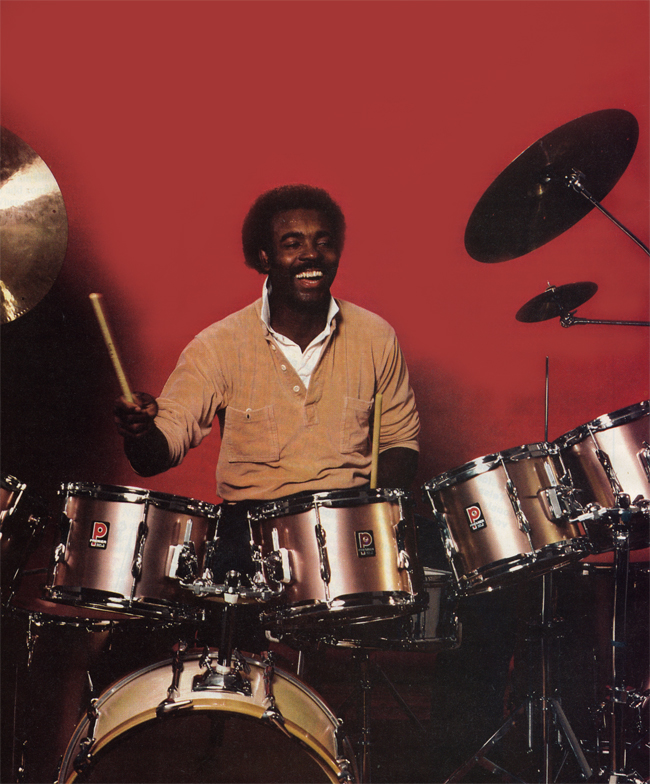

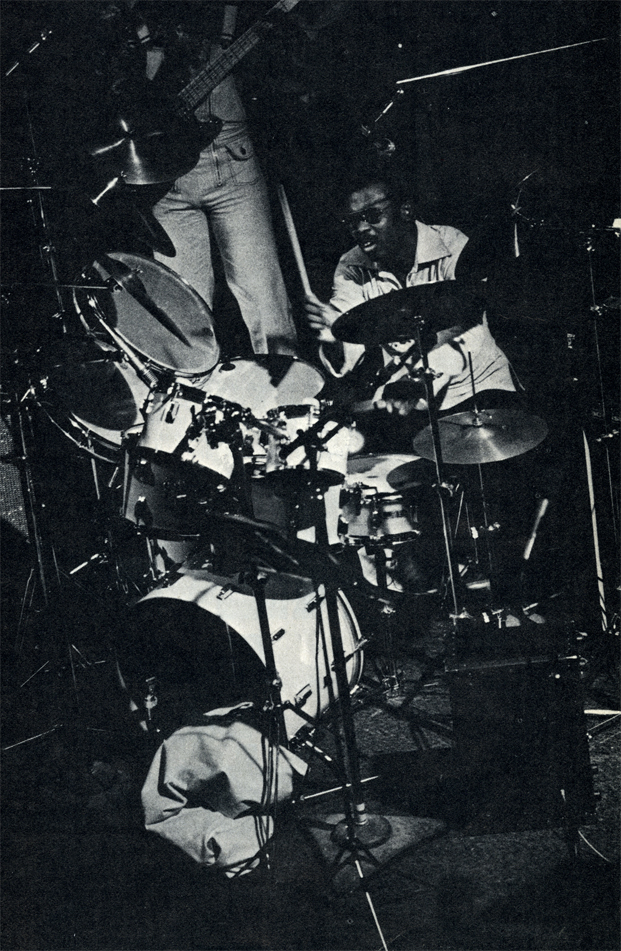

Back Through the Stack: Harvey Mason

“I never really thought of being a professional musician,” says Harvey Mason. “Music is something I did for fun and enjoyment, and coming from a poor family, there was no way I was going to do anything that wouldn’t make me a good living. There were eight kids in my family and we were on welfare and it was really hard. I thought I would be a lawyer, but in my junior year in high school, I read an article in Downbeat about Larry Bunker and studio musicians, and the money they made. When I saw that you could make a living doing studio work, and knew I enjoyed all kinds of music, I thought it was something I was definitely prepared for.

“That’s when I decided I would be a musician,” Mason recalls from his home, where it’s nearly impossible to perceive his profession from glancing about. After speaking with him, however, it becomes obvious that the scarcity of gold records on the walls is intentional and proportionate to his modesty. He has left few clues to reveal his status as one of the foremost session players of the last decade. In fact, Mason refuses to compile a list of those projects special to him in fear that he will offend someone by his accidental deletion. But the list for whom he has played is lengthy, including Herbie Hancock, Quincy Jones, George Benson, Barbra Streisand, Bob James, Elmer Bernstein, Henry Mancini, such TV shows as Chips and Benson, countless films, and endless jingles.

Growing up in Atlantic City, New Jersey, Mason’s first influence was his father, who played drums for the Army band. He recalls playing the roll for the “Star Spangled Banner” at age four, and getting his picture on the front page of the paper. At eight, he began to take lessons on the snare drum, and didn’t buy his first set, a single-lug Gretsch, until his junior year in high school. “For years prior to that, I always wanted a drumset, but we couldn’t afford it,” he recalls. “Every Christmas I remember running downstairs to look for a drumset and there wouldn’t be one. Advertisement

“When I was really young, I was just into reading and I didn’t play the drumset at all. I was in orchestras and bands and that’s really all I did. I had no direction as far as playing on a bandstand or anything like that. Then in junior high school, the drummer in the dance band got sick and there was a concert that night for the PTA. I was the best drummer in the school, but I had never played a set. I kind of had an interest, but since I didn’t own a set, I never pursued it. They asked me to play that night, and after that, I became interested in set. It was amazing. I sat down the first time at a drumset and I could play it. So I remember putting drums together and making a set, and using the crash cymbals and making them into hi-hats and all kinds of things like that. I did the same thing during my freshman year in high school and played in the talent show. Right after that, I got interested in jazz, which some of my friends were turning me on to.

“When I started going to shows and seeing Stevie Wonder and Motown bands and checking out the drummers, I began to get really enthused about playing. Musically, my interests were really wide because I was affected by a lot of music. I played piano in church and my interests were really varied. I took piano lessons, but not extensively. I was impatient and wanted to go faster than the teacher thought I should go, and faster than I was ready to go. Consequently, I never really put in the time I should have. I’m taking piano this year, though, and starting all over again. I can play functionally enough to play my own material and some other music, and I read slowly, but I really want to be good. I find more and more the need to be able to entertain myself on piano because drums leave a void in that way, as far as melodic interpretation, so I really enjoy it, plus it helps with writing.”

After high school, Mason went to Berklee School of Music for a year and a half, until he received a scholarship to transfer to the New England Conservatory of Music, where he completed his education. Mason says the choice to continue his musical education after high school was the best decision he could have possibly made. “It came from my background and not having any money, and not really wanting to fall back in that position anymore. I wanted some sort of what I thought was security, so if nothing else, I could at least be a teacher. I had all kinds of offers, even when I was in high school, to go out on the road and stuff, but I declined because I thought maybe it would be short-lived and there wasn’t any insurance. Advertisement

“That’s why I finished school. Even now, I feel that I could probably teach on a college level, and when I first came out to L.A. and I was getting my California teaching credential, I taught for six months at Hoover High School in Glendale, and that was fun. It was always sort of an ace in the hole. Plus, the Conservatory gave me a good musical background. I learned a lot about harmony and orchestral playing, and I got to play with all kinds of great conductors at New England. I became familiar with all the instruments, and as far as Berklee, I learned an awful lot about writing in a real contemporary style. And there were all kinds of great players there. Boston was a great place to be—all kinds of music, all kinds of great players. It was perfect. It was the best thing I could have done, rather than go out there and get locked into one type of music and probably neglect a lot of other kinds of music, which would have put a real narrow capacity on my interests and abilities. By going to school, I went to a melting pot of music, so school was absolutely perfect for me.”

Mason worked all through school as well, and in fact, on his first night at the dorm at Berklee he landed a job at the Pussycat Theater. “Someone called on the phone for a drummer and I was the first one to the phone, so I got it. It was great, because I had taken out a loan to go to school and had to pay $131.60 a month. I didn’t know where I was going to get that money. I was lucky I got that job.”

After that, Harvey gigged constantly in a variety of jobs, including at jazz clubs and belly dance clubs…with orchestras, percussion ensembles, operas, and R&B bands…once he even worked with Duke Ellington. He also began to work steadily at a club called the Sugar Shack, where the house band would back a lot of famous R&B performers who were touring through the area. And during his last year in Boston, he had the opportunity to gain studio experience by becoming involved with a studio called Triple A, where did jingles, religious albums, and various other projects. Advertisement

“I got to really think about drum sounds and really learned the kinds of compromises I had to make with my drums,” Harvey says. “I thought I knew, but I didn’t really, and I had to learn to bend and compromise that way. I have always been a sympathetic player because I’ve been in so many situations and I didn’t want to over-run the situations. I’ve always been in situations where I felt I was backing someone else up, and the object is to make them feel comfortable so they can do what they do the best they possibly can. I always wanted to have that kind of an attitude, rather than showing them up or anything like that. So going into the studio, I had to compromise, but it wasn’t hard for me to do that. You learn what to play and what not to play. By the time I went to L.A., I was pretty relaxed with recording.”

“I got to really think about drum sounds and really learned the kinds of compromises I had to make with my drums,” Harvey says. “I thought I knew, but I didn’t really, and I had to learn to bend and compromise that way. I have always been a sympathetic player because I’ve been in so many situations and I didn’t want to over-run the situations. I’ve always been in situations where I felt I was backing someone else up, and the object is to make them feel comfortable so they can do what they do the best they possibly can. I always wanted to have that kind of an attitude, rather than showing them up or anything like that. So going into the studio, I had to compromise, but it wasn’t hard for me to do that. You learn what to play and what not to play. By the time I went to L.A., I was pretty relaxed with recording.”

On his move to L.A. Harvey was accompanied by Sally, a trombone student who he’d met and married during his first year at Berklee. Sally’s family was from the West Coast, but Mason says they also settled there because of the abundance of record, TV, film, and jingle work. “I also didn’t want to go to New York,” Harvey says, “because I wasn’t crazy about the thought of going there and being surrounded by such a huge jungle, where there didn’t seem to be much organization. I thought it would be hard in L.A., but at least there seemed to be some organization to it.”

Shortly after moving to Los Angeles, Mason began to get session work. His first big break occurred when Marty Berman took a chance and used him on a big Texaco commercial, during which Ray Brown saw him and called him to do The Bill Cosby Show with Quincy Jones. The calls, however, were for Mason the percussionist. Harvey had played timpani throughout high school and had studied with Vic Firth of the Boston Symphony. “There are some instruments I’m more comfortable playing than others,” he explains. “Timpani is one of them. There are guys in this town who have been playing the tuned instruments, the bells and things of that nature, as long as I’ve been playing drums. Being realistic about it, they would probably be more at ease doing that than I would. When I first came out here, though, percussion was all I was doing, and I went on dates where I didn’t know what I was going to see musically. So I put in quite a bit of time studying it. There are points about me that are real strong, and there are other things that I guess aren’t going to be as strong, but it all worked out. I got hung a couple of times, but nothing really major or disastrous. I just went in and had a good attitude about myself and what I was doing, and I was able to pull myself through the situations. Advertisement

“In the meantime,” he continues, “I wasn’t getting any calls for drums, and I was wondering if my calling was percussion. I was doing a few record dates here and there, and they were even playing some of the records I had done on The Bill Cosby Show. I’d say, ‘That’s me playing drums,’ and they’d say, ‘Sure.’ There were a lot of drummers, but I guess it was a novelty that I played percussion. One night, The Sammy Davis Show was going on and the drummer was sick and couldn’t make it, so he recommended me to the conductor. I went in there and played drums and there were some people there, one being J. J. Johnson. He was doing a TV show on a regular basis and he began calling me both for drums and percussion. Once people started hearing me more on drums, they began to call me for that as well. I would prepare by checking out the artist’s every album to check out style, how the drums sounded on previous records, etc. For a long time I was playing percussion, so I would watch the drummers carefully to see how they would handle the various playing situations.”

Mason says that he’s grateful that he spent his early years training in all styles of music as opposed to joining a band, for it is that background that has made him the in-demand player he is. “A good studio player,” he insists, “is someone who goes on the date and feels at ease playing anything called for to make the artist happy, and is fully capable of doing that.” Still, Mason has dealt with difficult situations, citing particularly stressful Steely Dan and Seals & Crofts dates. “At this point in my career, though, artists generally give me creative freedom,” Mason says. “Sometimes I feel that people are intimidated and don’t want to tell me what to play, which is too bad, because they don’t want to give me an idea of where they want to come from. I want everything; I want it both ways. I want the people to be able to take me in and trust me totally to give what I think is best for the situation, and then I want other people to tell me. The only way you get new ideas and get to new points in music is by listening to other ideas. So I want it all.”

Mason says that he’s grateful that he spent his early years training in all styles of music as opposed to joining a band, for it is that background that has made him the in-demand player he is. “A good studio player,” he insists, “is someone who goes on the date and feels at ease playing anything called for to make the artist happy, and is fully capable of doing that.” Still, Mason has dealt with difficult situations, citing particularly stressful Steely Dan and Seals & Crofts dates. “At this point in my career, though, artists generally give me creative freedom,” Mason says. “Sometimes I feel that people are intimidated and don’t want to tell me what to play, which is too bad, because they don’t want to give me an idea of where they want to come from. I want everything; I want it both ways. I want the people to be able to take me in and trust me totally to give what I think is best for the situation, and then I want other people to tell me. The only way you get new ideas and get to new points in music is by listening to other ideas. So I want it all.”

In addition to the on-the-job hardships, Mason has also encountered the normal difficulty a session player has in keeping his work fresh, exciting, and stimulating. Production, playing live, his own solo career, and consistently expanding his musical avenues, in addition to maintaining a balance between his music and outside interests, have been the keys to his lack of stagnation and personal enthusiasm and growth. Advertisement

“You can get burned out after a while,” Harvey says, “and sometimes it gets hard to really stay up and always be cooperative, always be smiling, always look forward to going to the next date. For five years, I did three sessions every day and I really kept that attitude up. But after awhile I burned out. So at that point, I knew it was time for me to pursue the artist end of it a little more. So I did that and started to move into another area so my attitude wouldn’t get bad. If I were to go on a date with a bad attitude, it would hurt me more in the long run, so I started not taking as many dates. I hadn’t really predetermined to have my own artist career, but in 1972 some record companies expressed interest in my doing so. My notoriety at the time was unbelievable, working with Herbie Hancock, and when they approached me again in 1975, I decided to do it.”

He says he has enjoyed that aspect of his career tremendously, simply for the additional musical expression it affords him. When asked how it felt to be the focal point of a project as opposed to the background player, he says, “The success I’ve had has come from how I’ve played, which is being sympathetic and really laying down good pockets of interesting colors. When I did my album, I felt the focal point would be on the songs, the production, and the way everything was laid out—the whole musical environment, as opposed to just my drumming. A drum album is boring. I never even played a solo on the first record, and I had one song where I didn’t even play at all. I didn’t play on that song because it wasn’t necessary, and I was trying to say, ‘Look, I’m man enough, even on my own record, not to do that because it’s not what’s called for.’ So as far as my being the focal point, it wasn’t really like that. I was lucky enough to be able to produce all my records right from the beginning, so I was getting a really good experience of being in control and having the say in everything. It was a good experience that was leading towards another area, also in my own musical experience, and I began cultivating the interest of moving into production.”

While few realized Mason had been writing since high school, his audience became even more surprised when on his third album, Funk in a Mason Jar, he performed his own vocals. “When I was in church, I used to sing in the choir, and I used to do a lot of things with them. When my voice changed, I stopped singing, but with the way music had been going, for records to get airplay, there’s been a greater call for vocals. If you’re not going to get airplay, you’re not going to survive. My albums went from selling 50,000 to 250,000 when I added vocals. I sang on some of that and started taking some vocal coaching up until about six or seven months ago. I just couldn’t make a record and have someone else doing all the singing. I really felt I wanted to participate, although I wouldn’t say I’m a singer, per se.” Advertisement

After his third album, Mason went on a limited solo concert tour, which he says he’d like to do again soon. Aside from a few appearances with George Benson and Bob James, it’s the only live performing he has done in recent years. “I really enjoy seeing the public reaction to things, Mason says. “It’s good for you to see some appreciation. You hear it on the radio and see that everybody is into it, and that’s nice, but to see it right there immediately is really great. It really takes you to a different place, and it puts your playing on a different level. All the years I was doing studio work, though, I didn’t really feel that my live playing was suffering because I was playing so much, and in real challenging situations, which called for me not to always play the same way. A lot of people say if you play studios, you get stale. You have to listen to yourself, and if you’re playing the same things, it’s not going to be too pleasant to hear. You just have to keep going for different things and not be afraid to try stuff. I think the style a lot of people know me for is probably a jazz-rock situation, which received a lot of notoriety, but there are a lot of records I’ve played where people wouldn’t know it was me, unless they were really heavy listeners. I’m so aware of the fact of sounding like myself, that in some situations I’ll purposely try not to sound like myself, because it doesn’t call for that sound. So maybe I’ll play the ride cymbal with the left hand instead of the right, or play the backbeat differently, or use a different set of drums. I’m always trying to come up with something different, and all the different musical situations keep you stimulated.”

At the close of last year, however, Mason felt he’d overextended himself, working on his fifth album, MVP, while producing projects for Midnight Star, Locksmith, Casiopea, and Lee Ritenour. “For two months I was working every day, including weekends, and I don’t really want to be in that situation again. It was amazing, but the pressure wasn’t too much fun. I stopped running for two months and gained sixteen pounds. I wasn’t eating a lot, but I was just grabbing food on the run and sitting a lot, and I got into real bad physical shape. As soon as I finished all that stuff, I went on a ten-day fast and lost all the weight, and I began running again and got back down to 160. So I’m running every day, I play golf, I play basketball and baseball, and in any given week I may do two or three different activities. So right now I’m just doing dates and nothing else. This week I’m only doing four sessions, which is real nice and very comfortable, so I have time for other things.

“I’m glad I didn’t play in one band initially. I probably would have been bored. I enjoy so many different kinds of music. It was more fun to do all kinds of different things. Now I’ll produce a record, I’ll play on a record, I’ll write a song, I’ll go hear some music, I’ll go play some music, I’ll go run in a track meet, or play some golf. Two weeks ago I went hunting. I’ll go skiing, I’ll travel a little, I’ll go to New York and do some record dates and be there for a week or two. Then I’ll go coach baseball and basketball with my kids, or go watch my daughter ride in a horse show. There are so many different things to do.” Advertisement

Mason’s son, Harvey Jr., seems to be following in his father’s footsteps, a prospect about which Harvey Sr. does not seem to be worried. “As far as the possibility of my son going into the business, I just hope he prepares himself as well as he can. Right now, at twelve, he’s a good drummer. He can work in a lot of bands because he understands the function of a drummer from the standpoint of playing in a band, playing good time, good grooves, good fills, and not getting in the way. But as far as studio work, and the aspect of getting to the technical level where things might come up and not surprise him, he needs to work on things and expand his musical vocabulary. As far as being in bands, though, he’s ready to do that right now. He also plays piano, he sings, and he’s really ready for that already. If he wants to get into it on that other level…we’ve talked a lot, and he knows what needs to be done.

“To a lot of young drummers, I say to do all the listening you can, to everyone who is on record, or live. Try to evaluate what really makes them function in the setting they’re in. Try to add it to your arsenal or repertoire so that when you’re in a situation, you have more things to call on. Listen to the music and try to figure out what your instrument does in various situations. Don’t be intimidated by anyone musically, and just do what you do best and feel good about doing. All you can do is what you do. You can’t do what anyone else does. If you’ve prepared enough, have listened enough, and are musically sympathetic to a situation, you usually end up doing okay.”

This story first ran in the July 1981 issue of Modern Drummer. Original interview by Robyn Flans.