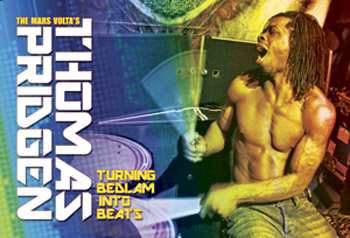

Thomas Pridgen: Turning Bedlam Into Beats

by Ken Micallef

“I want to play stuff that hasn’t been played before, stuff that will make people wig out.”

Twenty-four-year-old Thomas Pridgen unleashes the most rabid drumming in recent memory on The Mars Volta’s The Bedlam In Goliath. Of course, the band’s fans have come to expect madness and mastery from the innovative Long Beach, California group. But not even diehard Mars-heads were ready for the frenetic wall of drumming on tornado tracks like “Aberinkula,” “Conjugal Burns,” “Askepios,” and 2008’s greatest rhythmic display yet, the mind-bending, head-crushing “Wax Simulacra.”

Blowing through blistering 32nd-note full-set combinations, stunning single-stroke rolls, and blazing single bass drum patterns (sounding like double bass), Pridgen maneuvers “Wax Simulacra” like a crime fighter whacking criminals in Grand Theft Auto. And it doesn’t stop with the storm trooper intro. Once the groove is established, Pridgen seemingly continues to solo, jamming grace notes into and over a maniacal hi-hat/bass drum rhythm. A unison synth/tom roll crashes into the chorus, with yet another Pridgen assault–but somehow the groove is a mile wide and as deep as Bernard Purdie’s pockets.

Combining fists-of-fury rhythms with punk-rock power and Santana-fried Latin grooves, The Mars Volta is sonic danger personified. The band that blows through drummers like other bands change guitar strings has found their ultimate match in Pridgen, a player who has inspired more buzz among Modern Drummer readers than almost anyone else working today. (And that includes The Mars Volta’s first drumming titan, Jon Theodore.) Advertisement

Pridgen’s path to Mars Volta status is an epic tale in itself, one matching his quick wits with those of guitarist/songwriter Omar Rodriguez-Lopez. “Omar asked if I wanted to come check out the band,” Pridgen recalls from his home in El Cerrito, California. “We talked on the phone for a couple of hours, and then I went to Ohio to meet them. Omar invited me to a back room, where the whole band was set up. We jammed for a good thirty minutes. He then said, ‘We’re going to play that groove tonight in front of everybody.’ [This was for a huge show in Cleveland, when the band was touring with The Red Hot Chili Peppers.] It was spur-of-the-moment, but I guess he liked the fact that I didn’t care. Even now Omar throws a lot of spur-of-the-moment stuff at me. I guess I have a young enough mind to be down for the fly-by-night.”

Joining The Mars Volta is the logical next step to greatness for a drummer who can lay claim to numerous firsts: at age nine Pridgen won the Guitar Center Drum-Off; at age ten he became the youngest drummer to ever be awarded a Zildjian endorsement; and in 1999, at age fifteen, he was the youngest musician to ever receive a full scholarship to the Berklee College of Music. Pridgen eventually recorded with trumpeter Christian Scott and guitarist Eric Gales, and he recorded Omar Rodriguez-Lopez’s solo release Calibration (Is Pushing Luck And Key Too Far). Perhaps most importantly, Pridgen worked with Gospel acts including The Kenoly Brothers, Martin Luther, Kirk & Joni Bovill, and The G.M.W.A. Mass Choir.

Developing both astounding technique and deep grooves under the watchful eye of his grandmother, Addie, at the Berkeley Mt. Zion AME Church Of God, Thomas Pridgen learned how to glorify God with a nod to Dennis Chambers, Tony Williams, and Vinnie Colaiuta. Drum gods beware: This young turk is about to steal your thunder and claim your throne. Advertisement

MD: Regarding your technique, does your speed come from your fingers, or from using rebound–or do you play every stroke?

Thomas: I use every technique. When I began I used the finger thing, but I also started playing left-hand lead. I would practice and play left-handed at church. I would play all my ghost notes in my right hand and try to play my ride patterns in my left hand. The drums would be set up right-handed, but I would play left-handed.

MD: How did that develop your speed?

Thomas: Everything I practiced with my right hand I practiced with my left. That’s the main thing. If you do that you’ll even out your hands and pick up weird ghost notes. You’ll end up developing even more of a different style. Look at Will Kennedy; he looks so badass on the drums playing left-handed. So not only practicing left-handed, but playing that way really got my hands in shape. And most of the stuff I play is not as fast as it looks. It’s just that I’m alternating hands.

MD: In one YouTube video, you play a crossover, moving your left hand between your snare and floor tom at a blazing tempo. So strengthening your left hand has increased your overall speed?

Thomas: Yes, and you end up playing all kinds of interesting stuff. A lot of what I play, I don’t even know what I’m playing.

Advertisement

Thomas: Yes, and you end up playing all kinds of interesting stuff. A lot of what I play, I don’t even know what I’m playing.

Advertisement

I’ve studied Vinnie Colaiuta, Dennis Chambers, Tony Williams, and Elvin Jones, and I try to emulate them. My friends will sit by my drums and say, “Do your Vinnie licks” or “Do your Dennis licks.” Just from trying to do that and learning all these drummer’s styles and mimicking them has helped me create my style.

I don’t come from where Vinnie or Dennis came from; I’m not from Pittsburgh or Baltimore. So what I listen to and think is totally different. When I put my thing on [their styles], it’s weird. It’s trippy. People trip out on my ability to play odd meters, but I don’t even notice when I’m playing them. I don’t count ’em; I feel ’em.

MD: You play some killer single-stroke rolls on The Bedlam In Goliath, with great speed and sense of dynamics. You seem to play more singles than doubles.

Thomas: For singles, I listened to a lot of Will Kennedy, Dennis Chambers, and Billy Cobham. Those guys have a dynamic range with singles. They’ll crescendo up with their singles to a point where it makes it a lot more powerful. I worked on that a lot, as well as being able to do it softly.

Advertisement

I used to go to the NAMM show and get yelled at for playing too loud. So I learned pretty quickly how to play all my stuff at low volume. If you can play something at a low volume, you can usually play it loud. And if you can play it in the middle, you can crescendo and decrescendo. A lot of people overlook dynamics. It’s cool to play everything you know, but if it doesn’t register in a musical realm, then it’s wasted and pointless. So even when I play my stuff, I try to play it in a dynamic way.

See the rest of this interview in the September issue of Modern Drummer and catch Thomas at the Modern Drummer Festival Weekend, September 20 and 21, 2008.