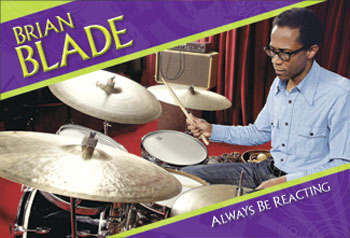

Brian Blade: Always Be Reacting

by Ken Micallef

Brian Blade has performed and recorded with some of the greatest musicians of this or any era. His explosive jazz drumming with tenor saxophonist and composer Wayne Shorter is documented on two amazing live albums, Footprints Live! and Beyond The Sound Barrier. Meanwhile, Blade’s more groove-based work with everyone from Joni Mitchell (Shine) and Bob Dylan (Time Out of Mind) to Daniel Lanois (Belladonna) and Norah Jones (Feels Like Home) further prove his chameleon bona fides.

But while Blade currently mans stage and recording studios with the upper echelon of music royalty, he cites an ordinary hotel gig as the real turning point in his passionate style. “I was fired,” Blade recalls from the New York offices of Verve Records. “I cancelled one night of a six-night engagement with my hero George French [bass, vocals] and Emile Vinette [piano], playing at the Sheraton on Canal Street in New Orleans. It was 1990; I was nineteen. I wanted to be downtown playing ‘modern jazz’ at Snug Harbor. In that instant when George said, ‘We’re going to get somebody else,’ I realized what the deal was. People would make requests, from ‘Green Green Grass Of Home’ to Monk tunes to Lee Dorsey’s ‘Working In A Coal Mine,’ and George and Emile could play it all and everything else. I was trying to play those songs and I realized I wasn’t prepared. These guys were teaching me and I didn’t see it then as something that I really needed. But looking back at it, I know now that it was special, that all-encompassing view of how to make music. No matter what it might be, it’s about serving the song.” Advertisement

Blade got that gig back, but in that instant of rejection he learned a truism that has served him throughout his still burgeoning career. On Seasons Of Change, the drummer’s third release as a leader with his band, Brian Blade Fellowship, he’s all about the songs, from brooding grooves to high-flying Americana to sublime straight-ahead. Following the band’s 1998 self-titled debut and 2000’s Perceptual, Seasons Of Change continues to position Blade as drummer-cum-leader, maneuvering his large ensemble with majestic drumming and passionate songs. Blade’s more explosive, kinetic style can be heard with a wide variety of artists, including organist Sam Yahel, saxophonist Joshua Redman, guitarist Wolfgang Muthspiel, and producer Daniel Lanois.

Blade’s amazing drumming on Wayne Shorter’s Beyond The Sound Barrier shows him to be ferocious, quick-witted, pliant, and always reacting. Like Alec Baldwin in Glengarry Glen Ross shouting “ABC! Always be closing!”, Blade’s motto seems to be “ABR! Always be reacting!” At times, barely able to compose himself, Blade will abruptly stand up to smash a cymbal or “round robin” his toms. He can as quickly lay way back in the cut to propel a groove, or tip his ride cymbal at triple-time to cut the edge of a jazz improvisation. Blade’s drumming conversation is as animated as Tony Williams’, as expansive as Elvin Jones’, and as magically quirky as Jim Keltner’s.

Blade never discusses the drums in isolation. The groove is always part of the music, part of the interplay between musicians, never a separate element existing in its own lonely space. With a vocal album in the works, the Shreveport native describes its music as a “Sunday record…maybe if you didn’t pray all week you might think about it today. It’s where I’m standing now, where I’ve been, and where I think I’m going.”

Advertisement

Blade never discusses the drums in isolation. The groove is always part of the music, part of the interplay between musicians, never a separate element existing in its own lonely space. With a vocal album in the works, the Shreveport native describes its music as a “Sunday record…maybe if you didn’t pray all week you might think about it today. It’s where I’m standing now, where I’ve been, and where I think I’m going.”

Advertisement

If you love Blade’s beautiful “ABR” drumming, you know where he’s going. In his second feature as a Modern Drummer cover artist, we attempt to trace Brian Blade’s future trajectory while understanding his everyday approach.

MD: In live performance, you’re often all over the kit: arms flying in different directions, your body leaning into or around the drums–you even get up from the throne to crash cymbals. You do things that a lot of drummers wouldn’t or couldn’t do. What does that kind of full-body drumming give you?

Brian: Hopefully it gives me flexibility and interpretation. It’s hard for me to see it any other way. As I’ve developed I’ve come to my own processes of how to get a sound. When I would watch my teacher, Johnny Vidacovich, play, I watched his whole physicality and animation. His sound was connected with the way he would move his arms and the way he would sit. I had to come to it on my own. Advertisement

Watching Elvin Jones was the same thing. His economy of motion…. I feel like I have to sometimes stand up to get that sound that Elvin got, because there was so much power and density and beauty in his playing. He almost looked like he was sitting in an easy chair; he flowed. So I’m just trying to achieve a sound, and that’s what happens.

MD: So jumping up to crash a cymbal gives you a different sound as opposed to if you were sitting down?

Brian: I couldn’t see it any other way. I feel like I’m all wrapped up in it. I never practiced posture so much…or how to economize my movements. It’s more like I saw a video of myself and noticed that my shoulders were up by my ears for fifteen minutes and I had to think about that. Okay, relax! Don’t tense up, even though you want to be intense. I’m finding a way to let myself be free and not tied to a stool. If I have to get up to hit the cymbal, at that moment it must be needed.

MD: So you’re feeling so passionate that you have to really smack it.

Brian: I’m so amazed at the privilege of playing with someone like Danilo Perez or Wayne Shorter–not thinking that consciously at the moment. It really drives you to move in a way. It makes me emote something that isn’t tame. Advertisement

The drums naturally embody this wild element. Not that I’m trying to be provocative, but the nature of hitting things must go way back. Just the primal aspect or sensibility in that and how to achieve a sound by hitting something, there are so many degrees within the subtlety. I’m always trying to get closer to what’s needed at that instant as the music moves.

There’s more to this interview in the July 2008 issue. Pick it up at your favorite newsstand, book store, or music store now!