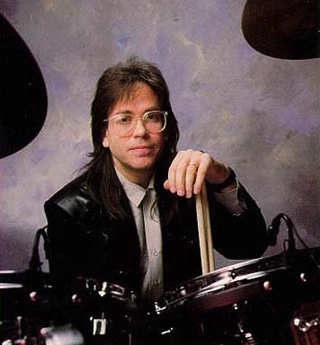

Jeff Porcaro: A Tribute

Ten years after his passing, the drumming and music community still feels the loss of the studio giant.

Ten years after his passing, the drumming and music community still feels the loss of the studio giant.

I consider myself among the fortunate people whose life Jeff Porcaro touched – and there are a lot of us. If Jeff Porcaro was anything, he was contagious. Being around him was like being exposed to the sun at its hottest, most warming and smiling degree. He was a ball of energy, a funny man with a laugh that still echoes happily in my ears, kind and sincere. He could mess with you in a teasing, fun way, but he never meant to hurt you. He was passionate about music, friends, and life, and was always ready with a compliment. We met as business associates and we became friends. I don’t use that word lightly, and while he had many friends, he didn’t use the word superficially either. I treasure the memory of our friendship.

Few deaths have affected me in the way Jeff’s passing did on August 5, 1992. The sheer loss of his energy on this earth was (and still is) devastating, and the tragedy for his family and his beautiful children–Nico, Miles, and Chris–was a pain that was hard to bear. When someone old passes, it’s sad and painful for loved ones. But there is comfort in knowing that it’s the correct order of the world. Jeff’s passing, at thirty-eight, was a tragedy. To this day, I find myself asking Why? The absence of his musical talents on today’s offerings is profound, but his legacy as a father, loved one, friend, and musician is indelible.

Jeff loved what he did. He resented anyone who put down the role of studio musician, for he took it seriously with a reverence that remained throughout his career. He truly appreciated the gig and what it took to create a song, was always a team player, and never cut corners. His work mattered to him, and the outcome was important. In fact, he was so self-critical that sometimes it came off as self-effacing. Advertisement

During the first interview I did with Jeff in 1982, he uttered the ridiculous comment, “My time sucks.” At that same time, he told me, “There’s not one record that I’ve done that I can listen to all the way through without getting bugged at how I played.”

Jeff told me, though, the Steely Dan tracks he did were his personal favorite performances. To him they represented the coolest music he could be asked to play. In fact, at the beginning of his career, he actually quit a $1,500 a week gig with Sonny & Cher to work with Steely Dan for $400 a week. And it wasn’t always easy.

During various interviews, Jeff talked about some of those tracks, such as “Gaucho” (Steely Dan, Gaucho): “It was Steve Khan on guitar, Anthony Jackson on bass, Rob Mounsey on keyboards, and Donald Fagen. The plan was to rehearse the tune in the studio, because those guys are meticulous. You rehearse from 2:00 to 6:00, take a dinner break, and at 7:00 you come back to the studio, start the tape rolling, and start doing takes. Well, this stuff is rehearsed so heavily that some of the spontaneity is gone. They demand perfect time, and it’s nerve-racking. Yet, I love it. That kind of pressure with those guys is cool, because, from my point of view, their music is the most prestigious music that’s ever existed. Advertisement

“So we started doing ‘Gaucho,'” Jeff continued, “and they went through every musician’s part so it was perfect. All they were going to keep at the end was the drum track, but most of the other musicians didn’t know that. I knew it from experience. Their idea is to get everybody else in the band and put them through all the shit in the world to make sure they play perfectly, just to get the perfect drum track. And these guys are sweating–beads of sweat rolling down their foreheads–shaking while they’re playing, and they don’t know that what they’re playing is never going to be used.

“We went to 3:00 in the morning, and I don’t know how many takes we did. Fagen walked out in the studio and it was something like, ‘Guys, does everybody know what this tune is supposed to sound like?’ We’re all looking at each other, going, ‘Yeah!’ He says, ‘Good. You guys know what it should sound like, I know what it’s supposed to sound like, then that’s all that matters. We’re done.’ And he splits. So we’re all sitting there in the studio like, ‘What?’ We all got pissed and said, ‘screw it, we’re going to work on this track and get it!’ So just Gary Katz (producer) was there, and we continued to do five or six more takes. That’s the kind of shit where most people would have packed up and split, but we just sat there feeling we had to get it–and we did.”

Robyn Flans

Advertisement