Back Through The Stack: Simon Phillips, December 1986

This is an excerpt of an article that originally ran in the December1986 issue of Modern Drummer magazine. For access to all of the great editorial from MD’s first twenty-six years of publication, check out our Digital Archive.

The first thing that comes to mind when setting out to write an introduction about Simon Phillips is that, to readers of Modern Drummer, he needs no introduction. He was first featured in the magazine in June 1981. Since then, his name has appeared regularly in the news and information sections, as well as among the poll winners. There is also the fact that many members of the international drumming community have seen Simon’s brilliant clinics. There are many superb English drummers around, but if you had to choose one who is indisputably accepted among his peers as being one of a special handful of players who are currently the finest and most influential in the world, it would definitely be Simon Phillips. This “drummers’ drummer” status could easily imply that an artist’s work is appreciated and lauded by the cognoscente, but is inaccessible to the public at large. However, this isn’t the case here. It is often said of successful players that their credits read like a “who’s who” of rock, or a “who’s who” of fusion, etc. With Simon, it is more like a “who’s who” of what has been happening over the last ten years. The brilliant nineteen-year-old drummer who amazed everybody when he first appeared in an arena-level band with Jack Bruce ten years ago had, for some time, already been a successful theater and studio musician. His subsequent career has thrown up the interesting contrasts of Stanley Clarke’s American fusion music to the very English music of Mike Oldfield, and the sophistication of Al Di Meola to the raw, punkish, brashness of Toyah’s band.

But just when you start imagining that Simon Phillips is some sort of human drum machine—someone who can play anything perfectly, with a human touch as well—and he must, therefore, have a one-track mind, it transpires that he is now breaking into producing and already has at least one hit album to his credit. He is at pains to point out that there is more to music than just playing your instrument and more to life than just music. He recently dabbled in motor racing. The attraction for him wasn’t the speed or the danger, but the precision. Simon is a man who likes to achieve precision and perfection in all he does. Now the motor racing has been relegated to the background, because he has been investing his money instead in a top-quality recording studio in his home. Advertisement

Not a man to do things by halves, if he is going to be a producer, Simon is going to have the best possible tools of the trade and have them at his fingertips. He has always worked, and continues to work, very hard for his success. The infinite care that he describes himself as taking with his instrument is indicative of the pains he takes over every aspect of what he does. There is none of the “I just hit ’em” attitude with Simon. He is a drummer we could all learn something from—that is, drummers, motor mechanics, presidents of multi-nationals….

MD: You use a lot of left-hand lead. How did that develop?

Simon: It started with using a large drumkit. If you play right-handed, you set the hi-hat a bit higher because you are crossing your hands, and then all the tom-toms are higher. I didn’t really like the look of the drumkit like that; I wanted to make it a lot more compact. I had seen a drummer play with his left hand on the hi-hat years before, so I had the idea in my mind. So I started trying to do it—swapping everything over that I did with the hands—and it felt very strange at first. Then I went to see Billy Cobham at the Rainbow. He came on, sat down at the kit, and started playing left hand on the hi-hat. That gave me the inspiration for saying, “Yes, it can be done.” Loads of other drummers play like that—Lenny White, for instance. I was living in a flat in Kensington at the time, and I couldn’t have a drumkit there because of the noise it would make. So I literally taught myself to do that with just a pair of sticks—swapping everything around. I suppose it took about a year until it all became natural. Then I reached a point where I played so much left-hand lead that I couldn’t play right-hand lead anymore. So I had to put a cymbal up on the right to force myself to play the other way again sometimes. That felt really strange as well. But now I am able to swap over between the two, which is very useful.

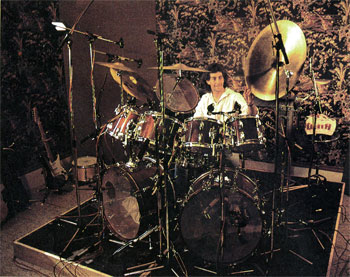

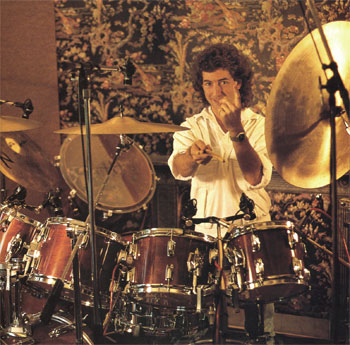

When we do Pete Townshend’s “Face the Face” live, I do it with two snare drums and two hi-hats. In the intro, I play the metal snare drum, which is to the left of the left-hand hi-hat, with my left hand while playing that hi-hat with my right. Then I switch to the snare drum that is in the usual position between my legs, still with the left hand, and my right hand plays the cymbals on the Cable Hat on my right. Later during the solos, I play the central snare drum with my right hand, and the hi-hat to the left of it with my left hand. So I can move around between the three positions; having that variety is great. Also, while you are playing, you can hit the odd tom-tom without having to cross over or do anything awkward. It makes you so much freer. I only have the hi-hat a touch higher than the snare drum, which means that the tom-toms on the left can come in much closer. People look at the drumkit and think that is’ enormous because they can only see my hair, but actually from behind, it is quite compact. I have spent a long time trying to get it that way, which was hard in the ’70s, because you didn’t have the holders you do now. Advertisement

MD: You mentioned “Face the Face” [White City—Pete Townshend]. Being fairly straight and simple, it isn’t the sort of thing that people might look on as classic Simon Phillips, but it’s got a great drum sound and a magnificent driving beat.

Simon: Some people think that that’s a drum machine. Pete had this idea for a dance-bop tune, and he played a demo of it for me with a drum machine playing that part. I thought, “Oh yeah,” because it’s one of these rhythms on which drum machines sound fantastic and real drummers sound rotten. It’s so easy. The bass and snare just do that. [He mimes alternate quarter notes.] But it has got to sound easy. If you are playing 8ths on a cymbal, the rest of your body can tense up, and the bass and snare beats will sound like 8th notes with 8th-note rests between them, instead of sounding like quarters.

MD: While we’re on the subject of the White City album, what about “Give Blood”? That featured in the Modern Drummer Best Recorded Performance chart for 1986. How does a more complex part like that suggest itself?

Simon: On that track there is a guitar riff that is all 16th notes with an echo unit, which gives it a steam-train effect. There was no bass on the basic track of that. Given that guitar riff to play to, it is just a matter of coming up with something that will enhance it. It needed to be something that wasn’t too complicated where the backbeat would cut through, but there were some other things happening that would chug it along. I’m always looking for something a little different to do. Perhaps that sort of 16th-note rhythm is a bit of a trademark with me; it’s something that I enjoy hearing. At clinics, I’m often asked about that: the little notes that you sort of hear, but they are not very loud. I like that sort of playing, as well as keeping a good old “crack” going.

MD: Please excuse the expression, but during the ’70s, you were something of a teenage session king. How did you manage to break into that so early?

Simon: [winces and smiles] When I was sixteen, I started playing in the pit for Jesus Christ Superstar, and it all came from that. The first thing was that I just did a four-track demo session for one of the people in the cast. I met some new musicians, the word got around, the other theater musicians heard of me…. I even got a session from somebody who just came to see the show one day. That’s literally how it all happened. It didn’t happen incredibly slowly, but it was gradual. It didn’t all suddenly happen “bang.” People hear of you, and you start to get a name. So within two-and-a-half years of doing the Superstar thing, it had built up fairly well for me. I went to New York in ’74 with a band, and I did a couple of record dates there as well. That was just through meeting musicians out there. And even though it was fairly small, it was handy to have had that experience of the New York studio scene. So by ’75, it had grown so that it was just crazy. Every day I was going into town and doing two or three sessions—two drumkits—one here, one there: moving about. That was an era when there really were a lot of sessions going on. It was before machines, and for everything you did, you had to have a rhythm section.

Advertisement

MD: Were you being called to do a particular style of playing or all sorts?

Simon: It was lots of different things. If you were playing with a particular group of people, that crowd would all be called to do things together. But you used to have to do all sorts of things. I even did some jingles for a while, which I hated because I would go along and set my drumkit up, get everything just right, then play one number, and they’d say, “That’s it.” I would say, “That’s it? You mean I’ve got to take this lot down again”? So eventually, I decided not to do any more jingles. I always had a rock ’n’ roll approach to sessions—denims, long hair, an angry-young-man attitude—and I used to find that a lot of studio musicians at the time were fairly straight. But they used to ask me to play, and that was fine.

MD: Were you uncompromising right from the start about your “live” drum sound?

Simon: Oh, yes. From the earliest times, even when I was a kid playing with my dad, things that I believed in were very hard to shake. I’d been in recording studios from a very early age—just being in that atmosphere—so a mic and a piece of tape were nothing new. I used to do it at home: editing and bouncing sound between two tape recorders.

MD: Did you ever get the feeling that people, perhaps, thought you were a bit precocious?

Simon: No. Although I’m sure that some people did, I never actually got the feedback from it. I was always brought up to be polite to people, so I think that everything I said and did would have been done very diplomatically. Sometimes I had to back down, and then I’d end up hating the rest of the date. Consequently, I wouldn’t want to work for those people again. Sometimes, though, you can make it as plain as you can that you don’t enjoy working for people, and they still keep calling you. You think, “What do I have to do”?

Advertisement

But generally, the whole session thing was very enjoyable. My attitude would be that I was going to play the best track I could. They might have an idea of what they wanted, and I would aim to give them that, plus add something a little different of my own. The experience that I gained from other musicians, as well as just learning about studios, was great.

When I started to enlarge the kit, that was talked about a lot in the studios. When I could afford to have a chap to carry my drums around, it all became double kits. I would turn up with a double kit for some ridiculous sessions, because for me, a double kit is much more comfortable to play. I’ve used one since 1974. I was laughed at sometimes, but the engineers used to love it. They’d get all the mics out and really get down to work. Then you would get the producer who would say, “Well, which ones do you use”? I’d say, “All of them, or perhaps none of them. It depends on the song.”

MD: Weren’t there instances when it was clear that all you needed was a bass drum, snare drum, and hi-hat?

Simon: That happens now, sometimes, but my kit is just delivered and set up, so it is all there anyway. And although they might feel that all the track calls for is a kick, snare, and hi-hat, I usually say, “Well, hang on. You’ve asked me to do this track, so you are probably open to any ideas that I can bring to it.” Quite often I’ll arrive at the studio and my chap will have brought the kit in, but he won’t have set it up completely and positioned it because I like to decide where to put it to get the best sound. Sometimes I’ll even listen to the track before deciding where the kit should go. I’ll either use the kick and snare without the toms, or I’ll find a use for the toms that the producer hasn’t thought of. But either way, I like to set up the toms on top of the kick drum. Even if you switch off all the other mics, these two instruments sound fuller, because the kit is resonating as a whole instrument. You can put up a kick and snare on their own, and they’ll sound okay—perhaps a bit thin, but very clean. Then you put the whole lot up, and it will make them sound so much more powerful. I suppose it’s like a piano string; play one note and all the rest will resonate, but take all the other strings out and play the same note, and it will sound very different.

Advertisement

MD: Can we backtrack? How did you reach the standard to be able to join Jesus Christ Superstar when you were only sixteen?

Simon: My father had a Dixieland band [the Sid Phillips Orchestra], and I grew up listening to his band and playing along to his music by putting a record or a tape on and playing to it. The music I used to be interested in was modern jazz, soul, Tamla/Motown—a mixture really. Then there came a time when I was twelve, and my father came home one night in despair about the drummer he had just had. My mother said, “Well, you’ve got a perfectly good drummer here. Why not take him out on gigs”? Dad wasn’t keen on the idea at first. He said that I was going to have to finish my schooling. They wanted me to have a good education, but it was already failing. [laughs] My mother said, “Look, however many schools you send him to, he’s still going to be a drummer.” So he agreed to try me on a couple of the smaller dates. I joined the band for the first date, and stayed with them from that time. I started doing the broadcasts, the records, and everything. I had four years of experience in a band in which the youngest person apart from myself was thirty. They put up with a hell of a lot really, because at twelve, I could play along but there were a lot of things missing: dynamics, all sorts of things. But I learned from the whole band. After about seven gigs when they couldn’t stand any more, one of them turned around to me and said, “Look, the bass drum—um, you don’t have to play it at triple forte every single beat. It can be nice if you play it quietly sometimes.” [laughs] Then they would play a record to illustrate what they meant. They had had enough of sitting in front of my bass drum and having to go “bang, bang, bang” through every number, but I think my dad liked it actually, because it was really old-fashioned and primitive. He liked that sort of thing; he hated modern jazz. He wanted things chugging along.

It was a wonderful training ground for me, but I ended up by the last year hating that sort of music. I wanted to play rock music or modern jazz. I went through a year of playing along to records in every time signature except 4/4. I wanted to get away from anything regular, so I practiced to Don Ellis records and Stan Kenton records, and learned how to play in 7/4, 13/8, and all that sort of stuff. The only time I played in 4/4 was on gigs with the band.

MD: What about more formal training? You had lessons with Max Abrams, didn’t you?

Simon: Yes. Max was very strict. He basically only really taught me to read music. He never actually sat down and taught me anything about drums. He would give you a chart, put a tape on, and you’d have to play it and play it correctly. He’d come in and say, “It’s wrong,” and you’d wonder why. Then eventually, he’d sing it to you the way it should be and go away again. It was a very funny way of teaching. He never said anything good. That might have been a good thing because it made me try harder.

Advertisement

There were lots of little factors that seemed to work together for me: the experience of playing with my dad and the tremendous encouragement from my mum. But a lot of it was finding things out for myself—listening to what a drummer did on a record and copying it. I actually used to copy the drum sound on the record with my kit, so that I could really get into the feel of the way the drummer was playing. If you’ve got a drumkit tuned differently, it gives a completely different feel. The drumkit should sound right for the type of playing needed. Sound has become more important. In the old days, you would just play your music regardless, but these days, you also try to make it sound really good.

Anyway, going back to my early experience: My dad died very suddenly, and I was left with a Dixieland band that looked as if it could continue. But by that time I hated the music, and also being a little bit of a purist, I felt that, without my father’s clarinet, anything else would have been second best. So I disbanded the band, to the disappointment of a lot of people. I decided that I would just have to do it on my own. I did a few rotten old gigs with a couple of bands, but I wasn’t on the scene and nobody really wanted to know. I was sixteen years old, and people only knew me for playing with my father. My mother was great at that time. I had left school, and she told me to go out and get a job. As musicians will, I said, “I’m a musician. I must play my music.” She said, “That’s fine, but you must earn some money. I don’t care how you do it. Be a doctor if you like.” So as sixteen-year-olds do, I felt very hard done by, but I got a job in an electrical shop. I was able to support myself and pay mum some rent. The house we had wasn’t huge, but it was a good size. Mum got some lodgers in. She managed to scrape through; I don’t know how she did it really. I had other things on my mind. I was thinking, “Am I ever going to play professionally again”?

The Superstar gig was a lifesaver when it came along. I suddenly got a call from the fixer [contractor], asking if I would be interested in coming along for an audition. I said yeah, and I thought to myself, “How did this happen”? A pianist named Dave Cullin, who did broadcasts and a few of the gigs with my father, was playing keyboards in Superstar. The other drummer was leaving, and Dave, bless him, mentioned me. He said, “He’s very young, but he’s great. He should be able to handle this; I know he wants to get into this type of music.” So I went out and bought the album. They dropped the parts over so that I could have a look at them. At that time I had bought a car because I had to have transport for the drumkit. I was only sixteen, so I couldn’t drive it; I had to get other people to drive me. I organized a driver—my mother—did the audition, and later that same afternoon, I heard that I had the job. Advertisement

MD: Had you had any previous pit experience, before landing what must have been one of the top jobs?

Simon: Yes, very briefly. There was another show by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice that was running at the same time. It was called Joseph And The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. I had a call to ask if I could come in and play at very short notice, because the drummer had been hurt in a car accident. So I went in and had a little look at the parts, and played the show more or less sight reading. This was virtually the first time I’d ever done anything like this. I’d hardly followed a conductor before. But my reading was good at the time. I’d done a lot with my father, and I suppose all my senses were up. I got through the first show, and I amazed myself. It felt great to be able to read a part, get it right, and still play around a bit. The conductor was very pleased. “You played the whole show beautifully, and you’ve never even heard it before.” I went home feeling fantastic, having achieved something that I’d always wanted to achieve—be able to read anything and make it sound as if I’ve played it before. When I got home, my mum asked how it went, and I said [dusts his hands], “Great! Fine! I can do anything now.”

I went back to do the show for the second time, and it was awful! [laughs] I just couldn’t do anything right. It was a good lesson: The first night I was scared and it really worked; the second night, I was really cocky and full of myself, and it was atrocious. I’m glad that it happened to me when it did, because when Superstar came along, I was prepared. On the second night of that show, I was ever so wary. It wasn’t until some time later that a major “tilt” happened—which it always does.

MD: You went from being a pit musician to a session musician to playing with many of the biggest names in the world. Could you tell us something about that?

Simon: You go through different ambitions. In 1975, I wanted to play with John McLaughlin and all these guys; I was buying their records. I was thinking that I’d love to play with Stanley Clarke, Chick Corea, and Jeff Beck; these were the people whose music I really enjoyed. The first big-name musician I played with was Jack Bruce. He was fantastic. I played with him for two years, and he taught me so much—about music, life, and everything. We went on the road for quite a while in the States, which was very good experience for me. Jack is still somebody who I admire and respect a lot. Whatever his popularity is like at the moment is another thing, but he still remains a great artist.

Advertisement

After Jack, I played with Stanley Clarke and Jeff Beck, and then Stanley, and then Jeff. [laughs] Later on, I played with Al Di Meola. But it got to a stage where it was all getting a little bit repetitive. I wanted to play in something a little younger; I had always played with people who were quite a bit older than I was. I thought that I would really like to play with some musicians my own age, but it was hard because nobody my age was playing the sort of music that I was playing, or if they were, I hadn’t met them.

I was watching Top Of The Pops one night, and Toyah was on. I’d seen her a few times before, and I started thinking that I’d quite like to mingle with the new “punk” crowd. I’d never done that; it might be interesting. And then, not long afterwards, Toyah’s producer called me and said, “Look, our drummer has just left, but we’ve booked into a studio and we need to do some tracks. Do you think you could come down and play for us”? I said, “Yeah, I’d love to!”

I went down there with my rig, and they’d never really seen anything like it before—the big drumkit with the big sound. They’d all been through the punk thing. But we actually got on very well. We did a couple of tracks. Then they asked me if I’d go out on tour with them, and I said no because I just didn’t think that it could come off. And then I started thinking that there were a few albums I had been asked to do, but there was nothing exciting. I could really dig going out on the road, and I turned around and said that I would. Advertisement

So we went off and did a European tour, and it was so funny. For the first time, I found myself being the “daddy” of the band—in the teaching seat. They didn’t know the difference between soft and loud. It had never really occurred to them, but they were great chaps. Actually, in the end, it turned into a really good band. It wasn’t technically wonderful, but there was a good onstage presence and feel. It was fun, and I learned from it. Whatever situation you are in, you are going to learn something. It all helps to form your musicianship.

Original interview by Simon Goodwin

Top photo by Joost Leijen; Middle and bottom photos by Annie Colbeck

Check out these other posts about Simon Phillips:

Simon Phillips (Update 2008)

Simon Phillips & Virgil Donati

Simon Phillips: The Drummer As Perfectionist