John Densmore: When You’re Strange

by Michael Parillo

The Doors are the subject of a fascinating new documentary film, When You’re Strange, which premiered last month on PBS’s American Masters after a theatrical run in the spring. The movie was directed by Tom DiCillo (Living In Oblivion) and features plenty of never-before-seen shots of the band and drummer John Densmore. All of the footage stems from the Doors’ active period of 1965–71, save some photos and film from the band members’ earlier days, and includes studio and live scenes plus brief interview segments.

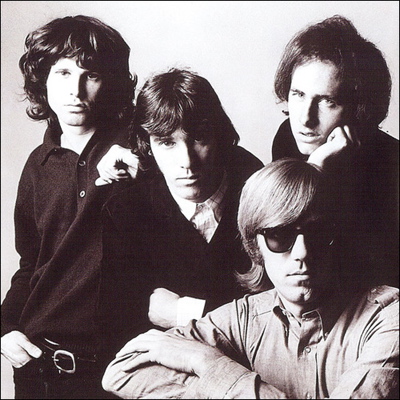

“You get to see me a little more, huh”? Densmore says in a phone interview with moderndrummer.com. Indeed, though this is not strictly a concert film, it includes priceless images of all four members of the Doors—Densmore, singer Jim Morrison, keyboardist Ray Manzarek, and guitarist Robby Krieger. In one brief but indelible shot, Densmore pummels his ride cymbal as Morrison dances mesmerized behind him, egging him on.

When You’re Strange is being released on DVD and Blu-ray on June 29. To view extras from the movie, visit www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters. And read on for our chat with Densmore, where we talk about the film, John’s melting-pot drumming style, and the Doors’ getting back to being a garage band for L.A. Woman. Advertisement

MD: The movie really reveals the Doors as an improvising unit, as does the new Live In New York CD box set recorded in 1970. Was improvising part of the plan from the outset, or did it just turn out that way?

John: Well, it just kind of happened. When Ray and I first met, we talked about Coltrane and Miles, so improvising was in our repertoire. Then it evolved, as Jim started to do freeform poetry in the middle of the longer things, like “The End” and “When The Music’s Over.” Let’s fool around here! If he would go out there and throw out a poem, we’d play a vamp and improvise and comment on what he was doing, or we’d answer or lead him or mess around—whatever. That grew over time.

MD: On stage, did you think about locking in with the “bass player,” Ray Manzarek’s left hand?

John: [laughs] Totally. The drummer’s first job is to have good time, and then you can fool around if you’ve got the first job down. So here’s the keyboard player having a solo, and his right hand takes off, and oh my God, his left hand—the bass player—takes off too. “Hold it down, Ray! I know you’re excited, but you’re rushing!” So I had to kind of pull him back when that was going on. Otherwise we were very locked. He wrote these simple, catchy bass lines, so I would just completely lock with his left hand. Advertisement

MD: The movie shows you to be a more physical drummer than some people might expect. You even have your fingers taped up at one point.

John: Yeah. I would tape ’em. As the concerts got larger I’d get blisters. Once in a while I’d look down at my drumhead and there’d be a little blood on it, and then I’d look at my fingers and there’d be blood. But you know, I didn’t know what I was doing—I was just into it.

MD: Did you woodshed a lot on and off the road in those days?

John: I practiced like crazy before the Doors. I played timpani in the orchestra. I played in the marching band and wore those stupid uniforms. It wasn’t cool back then; it was corny. But I really dug the power of a forty-piece ensemble. And I was in the dance band and took private lessons and woodshedded like crazy. Then I got gigs playing bar mitzvahs, weddings. A fake ID got me into clubs. By the time I got into the Doors, I wasn’t really woodshedding anymore. We’d rehearse, then we started recording and touring continually. So I didn’t practice at all. I was always playing. I didn’t practice—I slept.

MD: Your drum tracks are always thoughtful. It’s never just basic timekeeping but real parts, arrangements. Did you have an approach to crafting a beat?

John: Because of all this background of classical music and jazz and every kind of music possible, I had a sense of arrangement. I intuitively knew we needed a guitar solo or a bridge, or we needed to modulate or change keys, or whatever. And since Jim didn’t play an instrument, he said, “Let’s just do all this together.” So everybody gave 200 percent. And I had a big mouth about the arrangements. Likewise, with my playing, I just couldn’t help myself. I don’t know what I was doing. Advertisement

Springsteen asked me why I dropped those bombs on the tom-toms in the middle of “The End,” when it was real quiet. I said, “I don’t know!” But now that I reflect on it, it increased the tension. It was a real quiet section, then I’d play something real loud, just for a second. I’m a real fan of dynamics. That’s everything to me. Music, if it has a full range of dynamics, it’s like a human being breathing and going through all the emotions.

MD: I’ve always thought it sounded simplistic to say that everything with you came from jazz. You have the vocabulary and the rhythms of a jazz drummer, but you’re also a rocker, no doubt about it.

John: Yeah, I mean, I’m not playing bebop in the Doors. I can, but it’s not right. Jim would just start with some lyric, sing it a cappella, and we’d kinda go, “Well, it’s a waltz…” and figure out the chords. It would evolve, so I was just intuiting what was programmatic to what the song was saying. If he’s singing, “Five to one, one in five,” it’s real primal. So I’m not going to be playing some hip jazz shit; I’m going be playing primal grunts on the drums. I want to support what the lyrics are saying. Advertisement

MD: What were you listening to while the Doors were active?

John: Well, that was a pretty fertile period. Bruce Botnick, our recording engineer, got a copy of Sgt. Pepper before it was released, so we listened to that and went, “Oh my God!” And then we made Strange Days. There was a lot going on musically, so we were listening to everything. And old Miles Davis and stuff like that always fed us.

MD: What about the electric Miles stuff that was happening around then, like In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew?

John: Oh, yeah. Sure!

MD: What was it like to play gigs like the Long Island show featured in the film, where the crowd and authorities seemed intent on making it about things other than music? Were you able to let go and play when you were flanked by police?

John: The movie makes it look like we had a barrage of police at every concert and everyone was battling. It wasn’t like that all the time. Movies are dramatic. But that gig was weird.

For example, Oliver Stone [in Stone’s 1991 biopic The Doors] had all the cops on stage and Val Kilmer [playing Morrison] trying to get through them to sing. I said, “Oliver, this just happened a few times. That’s ridiculous—we wouldn’t play with all these cops on stage.” And he said, “That’s not cinematic.” Advertisement

A lot of times it would be very quiet—no cops on the stage—and it would be pin-drop time. We’d play “Light My Fire” and everybody would be on their feet dancing. Then we’d leave and our encore would be “The End,” and it would be silent. It would be ominous, real quiet. People would barely applaud when we finished. They were devastated. [laughs] Which was kinda cool. We thought, Hey, they’re not expending the energy on applause—they’re taking home whatever we gave them, and they’re gonna chew on it.

MD: There’s a sharp contrast in the movie between the laborious process of making Soft Parade versus, two albums later, L.A. Woman, which was produced by Bruce Botnick after your usual producer, Paul Rothchild, left. Was L.A. Woman a much more positive album to make?

John: It was a pleasure, yeah. Paul Rothchild taught us how to make records. And then he got too fanatical. I’d do a soundcheck on the drums, which used to take me an hour or forty-five, but by the time we got to L.A. Woman it was twenty minutes. Bruce said, “It sounds great. You know what you’re doing. You’ve made a bunch of records.” Advertisement

And that’s how we treated the takes on L.A. Woman. We just did a couple takes, on everything. There were some mistakes, and I would say, “Ray, remember on Miles Davis Live At Carnegie Hall, on the intro of ‘So What’ there’s this horrible trumpet error? Miles said he didn’t care, because of the feeling.” That’s what L.A. Woman is. Just passion—in our rehearsal room, not in a fancy studio. It was the first punk album! It was made cheap, in a couple weeks. And Soft Parade took months.

MD: What about the album in the middle, Morrison Hotel?

John: In between. It’s on the way to L.A. Woman. The Soft Parade had strings and horns and West Coast tenor sax solos. Ray and I had talked about that when we first met. So we finally got to do it, and as the movie shows, “Touch Me” was number one but the critics weren’t too crazy about it. It’s like we needed to go through that. We had planned it, we wanted to experiment with it, and we wouldn’t have gotten back to the roots of L.A. Woman in the garage if we hadn’t.