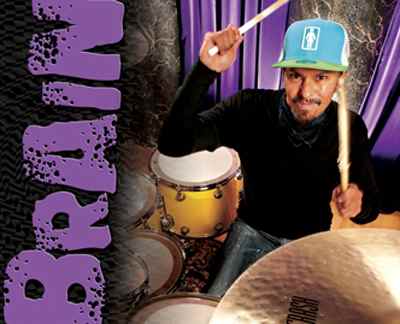

Guns ‘N’ Roses’ Bryan “Brain” Mantia

by Robin Tolleson

Brain gets asked to do a lot of interesting things these days, like playing time on a wagon wheel while recording with Tom Waits in an abandoned country church, or keeping a drumkit set up for six years in a haunted Masonic hall while working on Guns N’ Roses’ long-awaited latest album, Chinese Democracy. “Those situations are kind of opposite, but in a sense they’re the same,” the drummer suggests. “They’re different scenarios, but they’re both overblown. Somehow I feel comfortable in those situations. I don’t do too many studio sessions where I just show up with my set and read a chart. I’m used to getting involved and being part of the production and the ridiculousness of whatever it is. I just gravitate more toward that.”

Mantia was born in 1964, grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area town of Cupertino, and was first alerted to the skins by stickmen like John Bonham and the drummers of James Brown. He got serious in high school and cemented some chops at PIT in Hollywood, and in the late 1980s he played in the popular San Francisco party band Limbomaniacs. In the ’90s he hooked up with producer Bill Laswell for several interesting projects and did a stint with his longtime pal Les Claypool in Primus. Brain now lives in the Oakland hills with his wife and two-year-old daughter, near his recording space at Studio 880, where he spends time on turntables and traps.

Today Brain is developing a new funk project called SociaLibrium, and he hopes to be on the road this summer with Guns N’ Roses in support of Chinese Democracy.

MD: I’ve never heard anything quite like Tom Waits’ Real Gone album.

Brain: Yeah, it was Mark Ribot, me, Larry Taylor, and Tom. We recorded in this old…it was kind of a cross between a church and a barn. Tom says, “Show up at this place, this is where we’re going to do it.” I’m like, “Okay, is there a studio there? Should I call the studio owner”? He says, “Aw, no, nobody’s really there, there’s no phone service.” “Okay, is there a bathroom? A kitchen? Anything”? Advertisement

Basically he just brought the studio in there. The producer kind of set it all up and made it pretty comfortable. We sat around and just started jamming. He’d come in with an idea and go, “Okay, so maybe it goes like….” He basically told me, “Don’t bring a drumset, don’t bring anything that you can buy at Guitar Center.” So I went to some pawnshops and some junkyards, grabbed whatever sounded cool, and brought it. And he has his own stuff. We’d make a drumkit out of, like, a manhole, a carburetor, maybe a traditional cymbal that was broken, a 1930s Ludwig 26″ kick drum…. The snares were old, vintage, whatever was lying around. The other thing was, he asked me to bring hard leather-soled shoes. There was a bathroom that had a really nice-sounding ambience, and the tile on the floor sounded really good when you stomped on it. Most of the backbeats on that album were done by stomping on the bathroom floor.

MD: It definitely doesn’t sound like a traditional kit on Real Gone.

Brain: Tom had given me a cassette of him making all of these percussion sounds in his bathroom at like four in the morning. I took the cassette, blew it into Peak, which is a two-track editor, chopped it all up, and exported the WAV files. I have this program called MPC Maker, which allows you to create the programs on your Mac to put onto your MPC 3000. And so I just grabbed them, dragged and dropped them, threw them on the zip drive, and put them in my MPC. So when you hear [makes beatbox sounds] and all those weird vocal sounds, that was Tom. Next to the kit–which could have been me playing a log with a piece of metal in one hand and a mallet in the other–I also had the MPC 3000 with all those sounds set up. So that hip-hop-based beat stuff was me playing the MPC live–no programming–just live on the pads with his voice cut up from the cassette.

MD: It must have been quite a switch going from doing two takes per song with Tom, to the Guns N’ Roses album, which took about ten years to make.

Brain: [laughs] I think I have the record for my drums being set up for the longest time in any studio. I think they were set up at Village Recorders in Santa Monica for six years. Six years. That was another process entirely. Advertisement

MD: How did you get into that situation, and what was that process like?

MD: How did you get into that situation, and what was that process like?

Brain: The Guns album was in the works for fifteen years. Matt Sorum started it, then Josh Freese did it for four or five years, and then Josh quit. Then [guitarist] Buckethead got in there, and he and I have been friends forever. He told me that Josh had quit and said, “Axl’s an awesome dude. You should come check it out.” So I went in there, and I didn’t hear back from them for a while. And then one day I remember Axl calling me and saying, “You know, if you want the gig you can have it, and you can still be on other stuff. You can still do Primus or whatever you want to do.”

MD: What were some of the more memorable things you recall about that session?

Brain: [Producer] Roy Thomas Baker drove us around L.A. in his Rolls Royce to try to find the exact drums that we wanted for the recording. We went to every company, and it wound up being a mash-up of all the best drums we could find around L.A. We pretty much gathered the most ridiculous kit you could ever have, to rerecord Josh’s parts. Josh had come up with some pretty good parts for the album. Axl was like, “Hey, I like what Josh did, so could we start out by you doing his parts, but with your feel? Because your feel’s different.” So I went over to Sony Music and found the dude who did their orchestrations for films and asked if he could transcribe the drums on the thirty songs. He’s like, “All right, yeah, I’ll let you know when they’re done.” He would do about six a month–literally these six-page drum transcriptions of what Josh had played.

So we brought all those drums into the main studio at Village, where Fleetwood Mac recorded Tusk. I set up and started playing, and I was like, “Wait a second, man. We’re doing Guns N’ Roses here.” Advertisement

I talked to Jeff Greenberg, the owner, and said, “Jeff, man, we gotta have something better than this. I mean the room sounds great and this is cool, but you just had, like, Kenny G in here. We gotta get a vibe.”

He tells me there’s an old haunted Masonic temple upstairs where the Masons would give their speeches, and nobody ever goes up there. It was a theater. So we go up, he opens the door, and I’m thinking, We’ve got to set up here. We found the sweet spot and I set up the drums there…and that’s where they stayed for six years.

This was a Guns N’ Roses album–it had to be overblown.