Top-10 Rudiments, Part 10: Drag

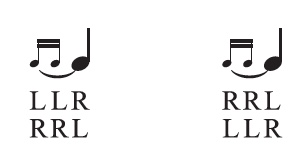

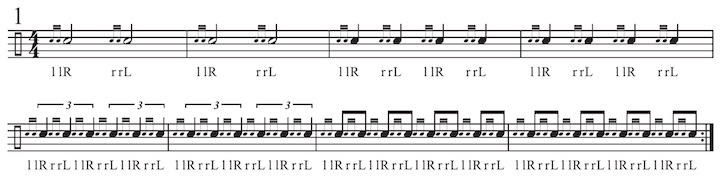

Drags are grace notes with no true metric value of their own; they must be tied to their primary notes. They’re often interpreted as closed buzz strokes, but for our purposes we should play them exactly as written, as open double-stroke diddles. (Once you’ve mastered open drags, it’s a good idea to go back and practice them as buzzes for variation.) Drags are also open to interpretation. They can be played wide, with a lot of space between the notes, or tight, where the notes are very close together and played as close to the primary note as possible without overlapping. (The style of music you’re playing, as well as the tension of your drumhead, will be determining factors in how you phrase drags.) At faster tempos, it’s practical and very common for drags to be played as precise rhythms, since there isn’t enough time to play them tighter.

It’s very simple to play drags slowly; just play a low diddle before a downstroke accent. The downstroke is stopped with the bead of the stick low to the drumhead, which ensures that you’re ready to initiate the next low diddle with the same hand. At this slow tempo, the drag is simply played as a low diddle using the wrist/finger alleyoop technique.

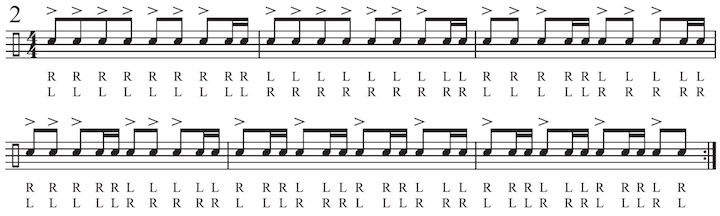

At fast tempos, the technique for playing drags changes drastically, and we need to implement a new hand motion. This is where the true value of the rudiment shows up. In this situation, there’s no time to stop the stick with a downstroke preceding the drag, since doing so would result in slowing down the tempo and tightening up the hands. (You’re asking too much of your hands to execute all of these motions in such a short amount of time.) To avoid this tension, the accent should rebound smoothly into the drag so that some of the accent’s energy flows through. The fingers must then squeeze out a low diddle with no prep time, and that’s the key hand motion—it’s all about finger control. It’s important to note that at this fast, flowing speed, stick heights will not be as defined as they were at a slower tempo, where there was time to stop the stick low to the drum. Advertisement

It’s extremely helpful to grip the stick between the thumb and first finger (the “first-finger fulcrum”) for rudiments like this that require finger finesse. Having the fulcrum in the front of the hand, with the thumb on the topside of the stick and no gap between the thumb and first finger, gives the end of the first finger and middle finger good access to the stick for small, quick motions. At tempos requiring this level of finger finesse, the back fingers have more distance to travel to track with the stick, and will therefore sometimes drop off completely. It’s wise to practice using multiple fulcrum points, because the more techniques that are available to you, the more options you have when executing your musical ideas. Switching on the fly from one technique to another will happen automatically once your hands are trained to know which one has the path of least resistance for various drumming tasks.

This article is culled from Bill Bachman’s popular Stick Technique book, which is designed to help players develop hands that are loose, stress free, and ready to play anything that comes to mind. The book is for everyone who plays with sticks, regardless of whether you’re focusing primarily on drumset, orchestral percussion, or the rudimental style of drumming. Divided into three main sections – Technique, Top-Ten Rudiments, and Chops Builders – Stick Technique is designed to get you playing essential techniques correctly and as quickly as possible. Also includes a bonus section two-hand coordination and independence.