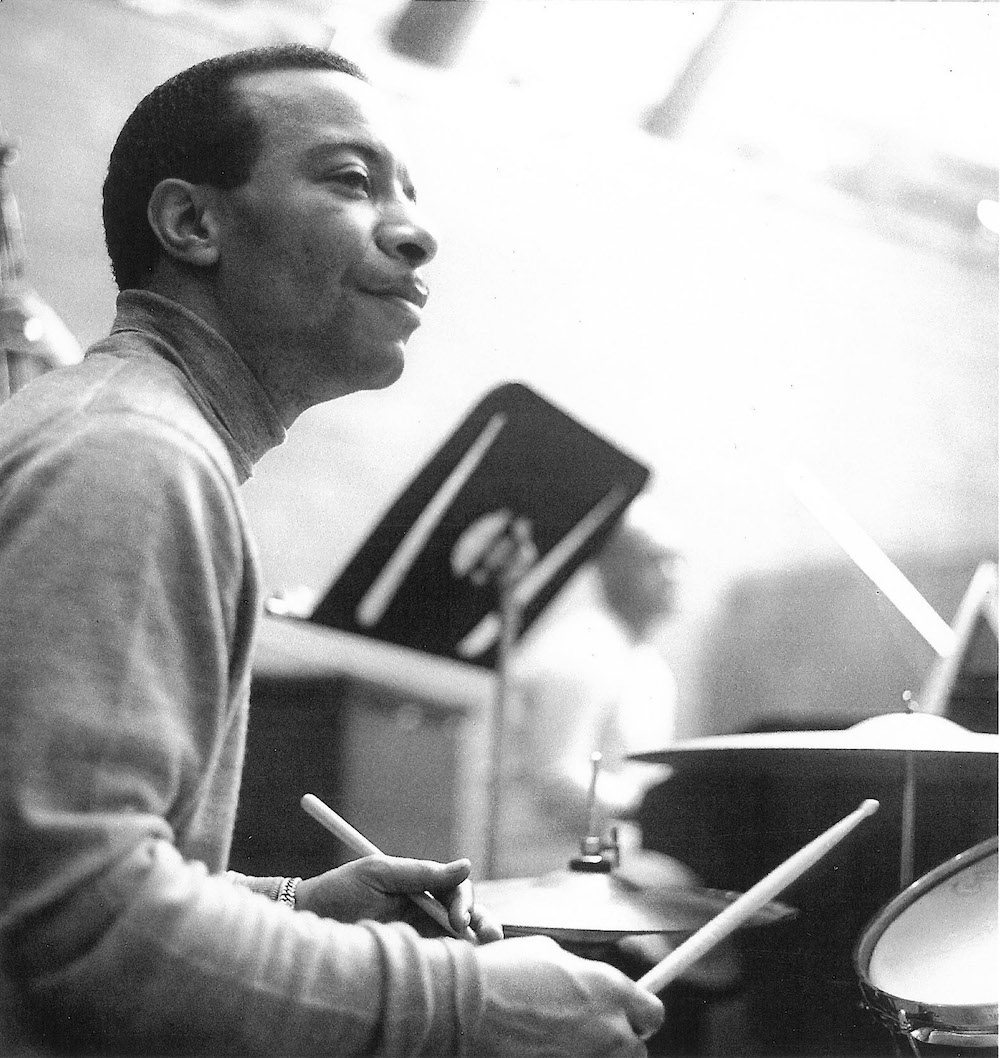

Grady Tate

by Mike De Simone

Editor’s note: Famed drummer Grady Tate passed away earlier this week. In honor of his long and varied career, here we present his June 2001 Modern Drummer feature interview.

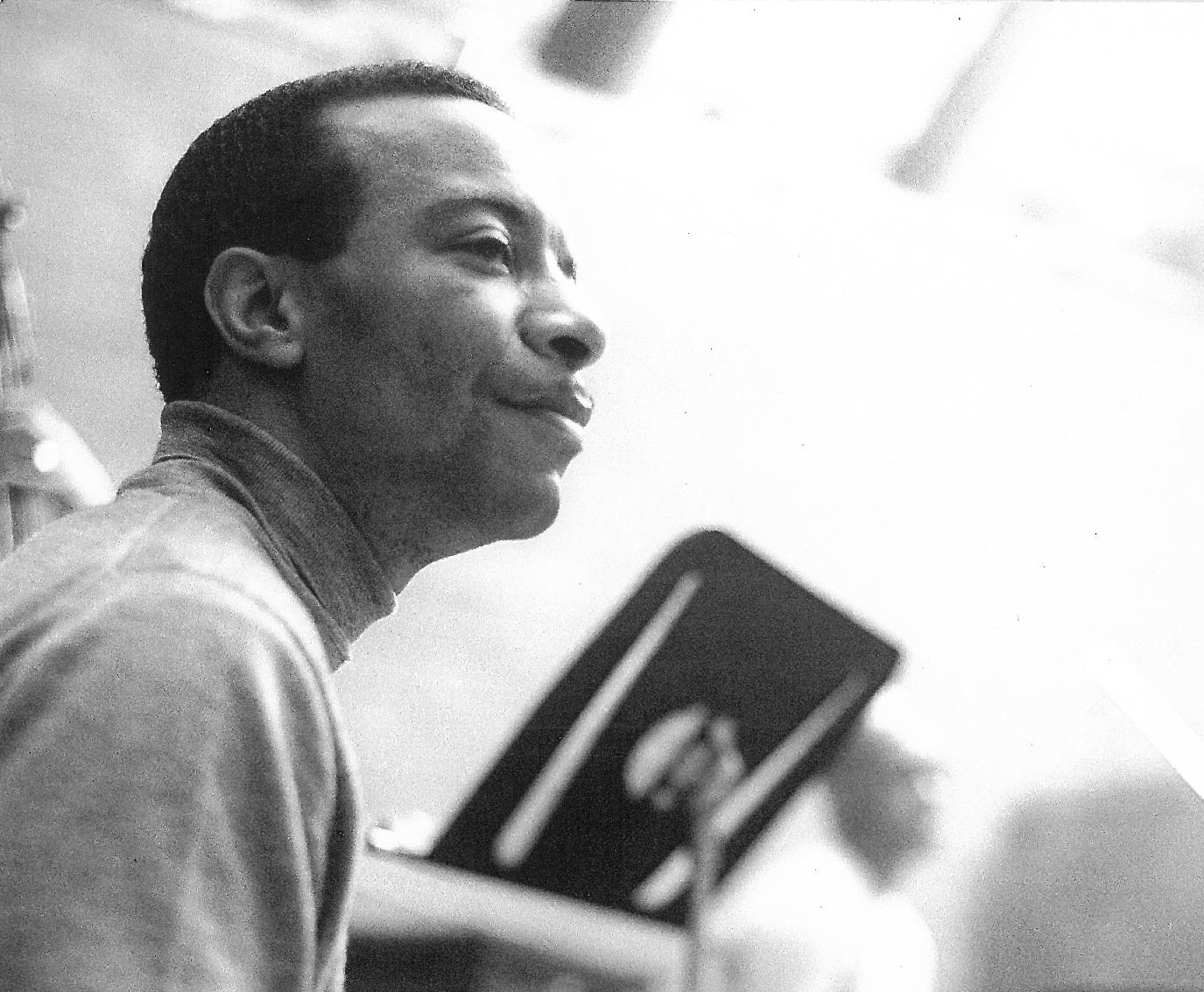

“I love quarter notes,” was the singular theme that ran through our conversation with master drummer and singer Grady Tate. Like a great jazz solo, he kept referring to that theme over and over to tie together his thoughts about his career in music.

Grady’s discography is so long that it’s impossible to count the exact number of recordings he’s done. The artists range from jazz greats Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Wes Montgomery to pop stars Paul Simon and Bette Midler. He’s also done countless jingles and film and television scores.

The list of artists Grady’s worked with is not only wide, but deep, which provides a portrait of a special artist. Grady Tate, the man, is honest, passionate, articulate, and most of all devoid of the “gift to music” kind of ego some musicians have. I watched as he approached the restaurant where our interview was to take place—smartly dressed, stick bag slung over his shoulder, with the confident walk of a man of considerable accomplishment. He also looked much younger than his sixty-nine years. Advertisement

So much of Grady Tate the drummer is tied to Grady the man. He speaks in a soft burnished baritone with a precise articulation that matches that of his playing. He listens carefully to every thought being expressed. He’s quick to laugh. And his work has always reflected his integrity and individuality.

The test of any musician is their longevity, and after forty years, Grady Tate is still in demand. As you read through our conversation, you’ll discover that it’s filled with sage advice and wisdom that contains something for everybody. Grady’s thoughts are peppered with references to many of the great names in music and drumming. What stands out is how those quarter notes of Grady’s have cut a path through jazz, rock, R&B, and pop—right up to his latest project, where he’s playing the sacred music of Duke Ellington with opera diva Jessye Norma.

*****

Grady Tate was born in Durham, North Carolina, on January 14, 1932, into a loving and supportive family. “My parents and relatives would buy records,” he recalls. “The first thing that I remember listening to is the phonograph. Light classical music is what impressed me. At five years old, I knew eight to ten light classical pieces. I didn’t do the drum thing until later on in elementary school, but in preschool I was singing light classical for ladies’ groups and small family functions. That’s what I like; I like pretty music.” Advertisement

Grady’s inspiration to play the drums started when his parents took the five-year-old to an amateur show sponsored by R.C. Cola. The contest featured a trio backing the singers and dancers. “I was quite impressed by the drummer; I had never seen anyone play a set of drums before,” Tate says. “Even though I was impressed with the drums, the emcee asked if there was anybody else who wanted to try out for the show. Before my parents knew what happened, I was on the stage singing ‘The One Rose.’ The judges accepted me as a singer and I won a crate of R.C. Cola. That was my first payment for performance.

“The drums still stayed on my mind,” Grady continues, “and I told my father about my interest. He asked, ‘You like drums?’ and I said, ‘Yeah,’ and I didn’t mention it any more. At Christmas, I came down and there was a full set of drums under the Christmas tree. He had to send to New York to get them.”

Grady goes on to state how proud his parents were of him, and he of them, and how fortunate he was to have been born into that family. He also speaks with great affection about his high school band director, Fillmore “Shorty” Hall, who had played in a number of territory bands and had taught the young Dizzy Gillespie at another school. “Shorty was an excellent jazz player,” Grady recalls. “The best I’d ever heard. He introduced me to timpani, something that not only dealt with rhythm, but pitches and changes as well. I’ve always had an incredible ear. I hear things and don’t forget them. As a matter of fact, I learned to read by rote. I would ask the trumpet player in the band what a figure sounds like. ‘Oh, that’s what that is.’ I never learned 1, e, &, ah, etc. I learned by seeing something and knowing exactly what it sounds like. I must say that was one of the biggest assets to my recording career. Advertisement

“My next thing was to listen to the orchestra to learn what was necessary to make that happen,” Tate continues. “I never dealt with drum music as such, because ninety-five percent of it had nothing to do with what’s happening in the band. So many people have destroyed their careers by reading exactly what’s written for them. My thing in recording is to look at the music, listen to what’s being done instrumentally, and see what elements of that drum music fit with what’s going down with the other instruments.”

I reminded Grady of an evening when we were out listening to a very good big band. He actually sang along to “Shiny Stockings.” He not only sang the melody, but the articulations of the lead trumpet part as well. “That’s the way I learned it,” he says. “If I’m going to hear it, I’m going to hear it from the source, and that’s the lead trumpet player. When you’ve got a passage that strong, you won’t get it from the saxophones. You get it from that power base [trumpets]. When it’s a saxophone thing, that requires another type of understanding. The brass is the boss, and the undercurrent of the saxophones is to nurture that power and let that power simmer.”

They’re playing their asses off, and they’re playing in the confines of the pocket.” Grady is smiling now, as he comments on the high level of young drumming talent today. “It’s difficult to play all of that stuff and make sure everything is right down the middle. The young kids are playing chops galore, power, stamina—and they still have that pocket going. Advertisement

“We can talk about the Weckls and the Cobhams of the world,” Grady says, “but they’re no longer young. They brought goodies to the table, and then the young kids took that and ran with it. There are young kids out in Iowa, Minnesota, and the Dakotas who are picking up recordings and hearing something that was done with two bass drums, but they didn’t see it being done. They’ll say, ‘Oh, that’s what a bass drum is supposed to do,’ and then they play it with one foot! That type of thing has caused a great revival of fantastic drummers. And there are some great female drummers too. I’m so pleased, I don’t know what to do.” [laughs]

*****

One of the seminal live dates of the ’60s, Ella and Duke at Cote D’Azur (Verve), had as much drama as music. Ella was heartbroken and exhausted due to the death of her half-sister, and Duke and producer Norman Granz were at odds. Ella took the stage with Jim Hughart (bass), Jimmy Jones (piano), Grady, and the Ellington orchestra. Considering Ella’s state, some drummers would have kicked and bashed like a wild bronco. But Grady set up a firm yet relaxed groove that got the fire going.

“Yeah, Jimmy Jones never played ’piano’ as such,” Grady recollects. “He played orchestrations; all the parts were there. It was a marvelous experience for me. And to listen to Ella…well! There again, it’s all about listening—to Ella, Sarah Vaughan, Peggy Lee, Joe Williams, Billy Eckstine. Just listening to these people while you’re working with them, you study them.” Advertisement

Drummers have long pointed to Tate’s playing on Bobby Darin’s classic version of “Mack The Knife” as an example of his sensitivity and restraint. Many players have been guilty at one time or another of bashing the hell out of the modulation section of that tune. Grady identified each key change by putting a little more edge on the beat and just a small “pop” that makes it a bit louder. But then again, Tate’s approach has always been more about intensity than bashing. “That’s just the way I heard it,” Grady says, modestly. “I don’t like being unable to hear whatever else is being played around me. Most of those recordings were done acoustically. If I bashed, I wouldn’t have been able to hear exactly what the bass and the piano were doing. And I certainly wouldn’t hear precisely what the singer was singing.

“There are all kinds of ways to play dynamically,” Grady offers. “It’s about having stick control. You can press your stick down into the head and still play a hell of a shuffle. It’ll be softer because you’re not getting any overtones. If you loosen up a little you’ll be playing at the same level. Loosen up more and you’ll be getting a lot more sound. When you hit that rim with a little more force, you’ll be loud.”

*****

The “A” team has different meanings to different people. On the New York session scene in the ’60s, it meant Grady Tate and bassist Ron Carter, who was his rhythm-section mate on a long list of recordings. “We’ve done lots of work together,” Grady enthuses. “We’re so akin in the way we feel about music. His sound is so warm, God knows he can play anything, and he has such a pocket. Ron and I agree on where it’s supposed to be. The dates went so much smoother with the two of us than they might have gone with others of equal or superior talent. It’s the communication that the two of us have—we have eye and body signals that allow us to do stuff without having predetermined it. We just take it to another level. Ron’s a monster, man.” Advertisement

During our conversation, the restaurant sound system coincidentally featured a number of artists that Tate had worked with. Grady constantly made humorous references to them. “I’ve done so many dates. I’d leave one session and immediately go to another, and I’d have to empty my head in between so I could start fresh on the next project. One of the things I’ve tried to do with studio work is play with each artist as differently as I can without losing what I do. I can’t remember all of the things I’ve done. I go to Japan, and after performances there’s a line of people with stacks of recordings that they ask me to sign. I have to turn them over and look, then I remember.”

One session Grady remembers well is recording the Benny Golson composition “Killer Joe” for Quincy Jones’ Walking in Space, which is often a young drummer’s introduction to jazz. Grady uses the session as an example of how to approach the song. “You have to know who Killer Joe is, for one thing,” Grady urges. “He’s perhaps the hippest dude on the street. He walks with a certain gait, his dress is of a certain code, he thinks a certain way, and he’s into everything. Everything has to be toned down because he doesn’t want to get busted by the man. He can’t be as flamboyant as he would like to be, so all of his stuff has to be underneath to keep the heat off.

“That’s why I love playing quarter notes,” Grady continues. “Killer Joe is walking [sings walking bass line]. He’s strolling. He’s not out there saying, Look at me! You have to be very cool with ‘Killer Joe’; you’ve got to play the character. I loved playing with [bassist] Ray Brown on that tune. That was fun. Ray plays… [sings triplet groove Brown plays throughout the piece], which gives ‘Killer Joe’ a little more life. I stayed where I was and let Ray deal, let him dance. He danced the hell out of that thing. And the band was incredible—all these characters. That’s something that Quincy is an absolute genius at. He brings together the right group of people who are individuals, but who at the same time can become a group.” Advertisement

*****

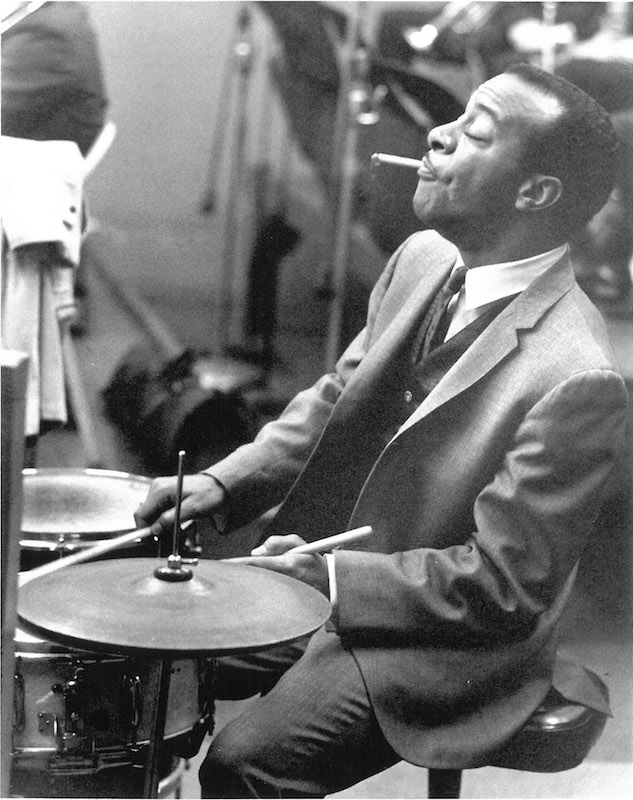

The ’60s were an exciting time in New York. Musicians walked from one recording date to another, and live gigs were plentiful. It was out of this firmament that Grady Tate solidified his reputation as a reliable and gifted drummer who could play any style with conviction.

The earlier generation of great jazz drummers who were in the studios refused to play anything that didn’t have a swing feel. Grady’s preference was also for jazz. But his unflagging commitment to make every date as good as it could be guaranteed that his professionalism overrode whatever opinions he held. Besides, it was a period of significant musical change, and Grady understood the importance of that. “The first thing that comes to mind is that we all wore suits, white shirts, and ties,” he says. “That was the dress code. We were very polite, and the music sounded like it. To me, it exuded a great deal of sophistication, and the artists we were working with were very sophisticated. Everybody spoke well, had a certain amount of education, and was well-traveled.”

As the “soul jazz” movement took hold in the late ’60s, the straight-8th-note groove became more prominent. Yet these were jazz dates, and they had to have that jazz vibe. “I studied all of my life to play the dotted-8th-and-16th-note pattern,” Grady says. “And then in the latter part of the ’60s, I was told that I must play 8th-note patterns. I had to devise some scheme where I could camouflage the straight 8th notes to give them a dotted feel and keep it within the jazz concept.” Advertisement

Stan Getz’s 1967 album Sweet Rain (Polygram) is one of the most important recordings in jazz, and it features a stellar performance from Grady . In fact, he had the unenviable task of replacing Roy Haynes, who had worked with Getz for a long time. Getz was also notoriously difficult, but Sweet Rain is perhaps the best example of mental practicing and care that Grady provides an artist. “I’ve listened to so much Roy Haynes,” he says. “Roy had been working with Stan, so he had Roy in his ears. Every drummer has ‘crips,’ things that you most remember him for. So I thought, Let me pick out ten of Roy’s crips. It will be a relief to Stan, and it’ll still be in the context of what’s happening. I prepare here [pointing to his head]. That’s the way I always prepare. I don’t sit down and practice. For Sweet Rain, I just thought about Roy.”

*****

As our chat with Grady continues, the conversation turns to the great session drummer Osie Johnson. Johnson is relatively unknown today, but he was part of an extraordinary rhythm section that included bassist Milt Hinton, guitarist Barry Galbraith, and pianist Hank Jones. That ensemble did many major recordings. “I learned decorum and an approach to recording from Osie,” Grady reminisces. “Recording at the time didn’t have all the sophistication that you have now, where you can make anybody sound the way you want them to sound. The sound of each player was so individual at that time. You could say, ‘Oh, that’s Osie.’ You could pick out all the cats. You had to be sober and really think seriously about what you were doing. You would never play what you played on a live gig on a recording. That was the one thing that aced a lot of cats out of work in the studios. They would come in and try to play it the way they would play live.

“Osie Johnson was as sweet a cat as you could meet—big smile, just a perfect gentleman. That’s another thing—and maybe cats don’t want to hear it: There are a lot of guys out there who can play, but if you’re going to work at this or any other instrument, you can’t have an attitude. Likability is the thing. If people like you, you’re going to get more work. If you’re a nasty human being, it takes too much time and energy to work with you.” Advertisement

Grady also feels that young drummers today rely too much on educational books and videos. He sees this partially as a financial issue. “You have to be pretty well-heeled to go to a jazz club,” he suggests. “You just can’t walk out and hear people anymore. If it weren’t for the Japanese and the Europeans visiting the clubs in New York, most of them would fold. Americans don’t give a shit about jazz, and those who do don’t care to spend a hundred bucks to go hear it. Drummers are going into rock because that’s what’s going to make them money.”

As a faculty member at Howard University, Tate sees first-hand what young musicians contend with today. “I’m at Howard to teach jazz vocal improvisation,” Grady explains. “I also coach a couple of drummers and critique their playing, just by listening and looking at them. But I’m not a drum ‘teacher’ because I didn’t study drums the way I did voice.”

Tate has in fact had quite a successful career as a singer, with a number of recordings and live performances to his credit. Of course, Grady isn’t the only sticksman to make a name for himself at the front of the stage. Mel Tormé, Don Henley, and Phil Collins come immediately to mind. Grady feels that the role allows him an even deeper understanding of the drummer’s duties. “I’ve had problems with drummers,” Tate admits. “They either don’t accept their role, or they underplay because they’re intimidated. Advertisement

“I try to make the drummers who work with me be as comfortable as possible,” he continues. “One of the ways I have of ensuring this is by listening to what a drummer plays—not on my gig, but on his gig. I’ve also got to have a person who plays brushes, who can groove with them not only on ballads but on uptempo tunes as well. And I don’t want to hear everything that a drummer can play. It’s about selectivity. You have to select what you’re going to play behind a singer. You have to find out what makes a singer go. It’s a matter of trial and error, and you should be able to tell what’s happening even if you’re looking at that person from the rear. You just have to be aware.”

*****

In the early ’80s, the word spread like wildfire that Grady Tate was going to play a Broadway musical. Drummers all over New York were excited about the prospect of getting to hear him live for two uninterrupted hours. The show was a retrospective on the career of singer-actress Lena Home, A Lady and Her Music. What made this a drumming event was when one of the most powerful critics in New York, Stuart Klein, said in his review, “The music was brilliant due to the superior playing of jazz great Grady Tate.” It’s a rare event indeed when a sideman is mentioned for his contribution to a musical.

The day this writer attended the show, there were three other drummers in the audience. With all due respect to Lena Home and her magnificent career, we had come to hear Grady. The show covered musical genres going back to the ’30s, and Grady covered it all with ease. He was flattered when I told him about the review and how much he has meant to drummers the world over. “I’ll be darned, I’m totally unaware of that kind of awareness of what I do,” he says. Advertisement

That’s not just Grady being modest. “I don’t think about it,” he explains, “because I never thought of myself as a drummer, and I know how little I can play. I’ve always said, How can I approach that sound and how can I play much less to really bring the music out? I don’t have any chops, never really thought about them. I hate solos; I can’t play one to save my life. I think of myself as someone who can keep time. When I think about great drummers, I think about Billy Cobham, Buddy Rich, and Dave Weckl, cats who are incredible. I can’t do any of that stuff with my hands. All I do is keep time.”

*****

With all of the recordings, film and television scores, and live dates he’s done, Grady gave special care to the work of composer Oliver Nelson. “Oliver Nelson was one of the most inventive and creative talents I’ve ever had the pleasure of working with,” he says. “Man, he wrote things that defied description. The music was coming from pure jazz—so incredibly difficult. I think that’s when I started wearing shades in the studio, so that neither he nor the band could see the fear in my eyes! Pressure does that to you sometimes. There’s always some thing that you can’t do comfortably.”

A situation that always was comfortable for Grady was when he worked with percussionists Ray Barretto and Johnny Pacheco. Together these three men have recorded some burning grooves, especially with Latin-jazz pioneer Cal Tjader. “I love working with Ray and Johnny,” Grady says fondly. “They’re both jazz fans. The conga players who play that 8th-note groove drive me nuts, especially when you’re trying to play dotted-8th-and-16ths. Ray and Johnny play the conga groove and swing their butts off. We used to do all kinds of jazz dates together. When playing with a percussionist, you have to get out of the way and know what and when to play. That’s why the quarter note is so slick. I didn’t have to play much, and it fit perfectly.” Advertisement

As we began to talk about working with Paul Simon, Grady spoke of his genius for music and lyrics. But then Grady immediately jumped to Simon’s long-standing drummer, Steve Gadd. “Whew, talk about a demon! Steve’s got that laid-back pocket— it’s just indescribable. He just sits down on the beat. He’s a bad, bad young man.”

When I mentioned Steve’s driving quarter-note groove on “Love for Sale” from the Buddy Rich tribute album Burning for Buddy, Grady reintroduced the theme of our conversation. “I love quarter notes. I do more with quarter notes than I do anything else. That’s just the way I feel.”