Famed Afro-Caribbean Drummer Steve Berrios Passes

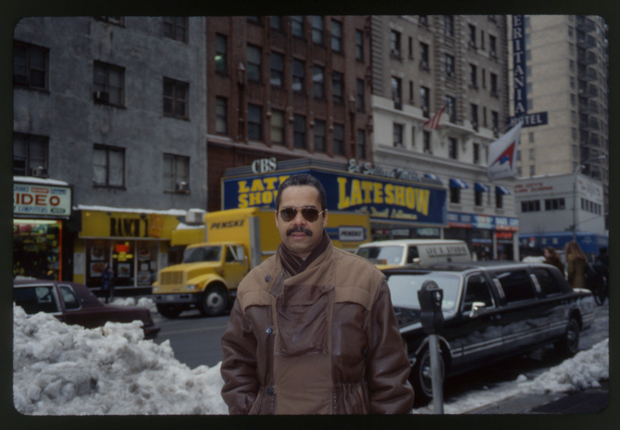

Steve Berrios in 1994, standing at the corner of Broadway and 52nd Street in New York City, where the original Birdland club once stood

Steve Berrios in 1994, standing at the corner of Broadway and 52nd Street in New York City, where the original Birdland club once stood

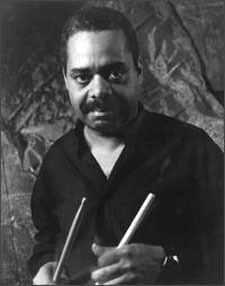

Modern Drummer is sad to announce that Steve Berrios died this past week at the age of sixty-eight at his home in Manhattan. The drummer was among the most innovative musicians to fuse Afro-Caribbean and jazz. Berrios had an impressive career, featuring work with influential Afro-Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaría, jazz legend Max Roach, and Latin-jazz pioneer Tito Puente. The September 1994 issue of Modern Drummer magazine contained an interview with Berrios that touched on a range of topics, from his upbringing in New York City to his unique approach to drumset and percussion. Here we present that article in full.

Steve Berrios: New York City Rhythmatist

by Ken Ross

Steve Berrios is regarded as one of the most influential drummers to successfully fuse Afro-Caribbean and jazz music. Since his early years with the legendary Mongo Santamaría band, Steve has been pioneering new and innovative applications of Afro-Caribbean rhythms to the drumset. Equally adept at jazz, his unique versatility demonstrates a hard-driving and swinging style.

Steve’s multicultural talent is documented on over one hundred recordings with such diverse artists as Max Roach, Tito Puente, Michael Brecker, and Carlos “Patato” Valdez. He is currently a member of Max Roach’s M’Boom ensemble and Jerry Gonzalez’ Fort Apache Band. Advertisement

Berrios grew up in a very musical environment at a very opportune time. The 1950s was a golden era for music in New York City. The mambo craze was enjoying tremendous popularity, bebop was taking hold, and rhythm & blues exploded on the scene. This was reflected in the city’s thriving nightlife, which offered many venues for musicians to perform. Clubs like Birdland, the Palladium Ballroom, and the Apollo Theatre featured such legends as Miles Davis, Tito Puente, Art Blakey, and Machito. “It was great,” Steve recalls. “We would check out Miles at Birdland, then run across the street and catch Tito at the Palladium. I really feel blessed to have been born in New York City.”

Steve recalls that the Berrios household was always alive with music and friends. “My parents were born in Puerto Rico but grew up in New York City. My father was a professional drummer; he played with Marcelino Guerra’s band and Noro Morales’ band in the ’40s. They were really popular at the time. When I was a child, there were always musicians at our apartment, and we had records playing all the time—stuff like Duke Ellington, Tito Puente, Puerto Rican folk music—everything! My dad used to keep many of his instruments at home: bongos, timbales, and sometimes his drumset. When everyone left the apartment I would set up all of his stuff and try to play along with the records.”

Steve’s musical education extended to formal lessons on the trumpet. He played all through school, then took private lessons. He eventually won numerous amateur contests at the Apollo Theatre.

But his big career break came on the drums, when his father asked the youngster to take over his chair at the Great Northern Hotel. Steve explains, “My father always heard me banging around the house, and he knew I could play, so one day he asked me if I wanted his gig. A steady gig at the age of nineteen—are you kidding? We were the house dance band, so we played all styles of music: cha chas, foxtrots, tangos, and paso dobles. Every Sunday we’d have a matinee show that featured guest bands. One Sunday Mongo Santamaría’s band played opposite us, and after the gig he came up to me and told me he really liked my playing. He had known my father, and I was real familiar with his music. Next thing I knew, he asked me if I wanted to join his band—and that was it!” Advertisement

Berrios spent the next twenty years of his life working on and off with the legendary bandleader. It was during this period that he developed into one of the most innovative and influential drummers ever to adapt Afro-Cuban rhythms to the drumset. “When I first joined Mongo’s band,” Steve says, “I played a standard drumset— which I used on boogaloo-type tunes. For the more traditional Afro-Cuban stuff, I switched over to timbales. Eventually I combined both instruments. Gradually I started adding more percussion, and the rhythmic patterns became more sophisticated.

“I use a lot of bata rhythms in my playing,” Berrios continues, referring to the sacred music and drums associated with the Afro-Cuban Santeria religion. “Also, I don’t really consider jazz and Afro-Caribbean different musics. Of course they have different characteristics, but I don’t think of it as going from jazz to Cuban to whatever. Music is music! I don’t even like the idea of putting Afro-Caribbean music in clave [the two-measure rhythm that serves as the foundation for most Afro-Caribbean music]. I’ve played with some of the greatest musicians in the world: Francisco Aguabella, Julito Collazo, Armando Peraza, and Carlos “Patato” Valdez, and they never once said, ‘This is in 3-2 clave’ or ‘This is in 2-3 clave.’ It’s just music; you just feel it.”

Berrios says that the heart of his playing is based on studying people and their cultures. “I think it’s important to learn the culture before you even consider the technique. For example, if you go to Juilliard to study your instrument, it’s a requirement that you study the great composers and learn all about their music and history. It’s the same thing with the music I’m playing. You should learn the traditions and customs, speak the language, and eat the food. That’s how you learn the music. I’ve had students ask me to teach them beats. It’s not about beats.”

Advertisement

Berrios says that the heart of his playing is based on studying people and their cultures. “I think it’s important to learn the culture before you even consider the technique. For example, if you go to Juilliard to study your instrument, it’s a requirement that you study the great composers and learn all about their music and history. It’s the same thing with the music I’m playing. You should learn the traditions and customs, speak the language, and eat the food. That’s how you learn the music. I’ve had students ask me to teach them beats. It’s not about beats.”

Advertisement

Through his work with Mongo Santamaría, Steve’s reputation as a premier drummer and percussionist reached an international audience. He toured the world extensively and performed at festivals with such artists as Randy Weston, Kenny Kirkland, Paquito D’Rivera, Hilton Ruiz, and Art Blakey.

In 1980, Berrios made history when he joined Jerry and Andy Gonzalez to form what was to become the Fort Apache Band. This became one of the most significant bands in the decade to fuse folkloric Afro-Caribbean music with jazz. Steve recalls how he joined the group. “When I went on the road with Mongo in 1968,” he says, “I rented my apartment to his son Monquito. Like his dad, he is a musician/leader. The bass player in Monquito’s band was Andy Gonzalez, Jerry’s brother. They were about five years younger than me and knew about me. Jerry and Andy would go to my apartment, hang out with Monquito, check out my records—and steal some. [laughs] Anyway, Jerry managed to get a deal to do a live recording in Berlin, and he asked me to do it. When we met the producer in Europe, he asked Jerry what the name of his band was. Jerry didn’t have a clue so he blurted out, ‘Fort Apache Band’—being from the Bronx. That’s when I officially became a member.” That debut recording—The River Is Deep—was a success, and Berrios played a vital role in giving the band its signature sound, fusing elements of jazz and Afro-Caribbean music with his unique style.

Another milestone in Steve’s career came in 1991, when he joined Max Roach’s M’Boom ensemble. This group is comprised of world-class percussionists well versed in a multitude of percussion instruments, from exotic to folkloric to mallet keyboards. Joe Chambers, a member of M’Boom, had recommended Steve after the unfortunate passing of the great Freddie Waits. “It’s definitely an honor to be a member of this ensemble,” Steve says. “One of the real challenges is that each member must alternate playing all the instruments.” Advertisement

Although Berrios is most comfortable playing drums in a supporting role, such as in Fort Apache and M’Boom, he recently stepped out of character to do his own video, Latin Rhythms Applied To the Drumset (Alchemy Pictures). On it, he demonstrates many authentic Afro-Caribbean rhythms and their applications to the drumset. Segments feature Berrios in an ensemble with the famous congero Carlos “Patato” Valdez, Eddie Bobe on percussion and vocals, Joe Santiago on bass, Larry Willis on piano, and Jerry Gonzalez on congas. Steve breaks down the rhythms he is playing and explains how he applies these ideas to the drumset.

“At first I was going to quit and give the producer back his money,” Berrios recalls. “He wanted a very structured approach to the video, but I wanted it unrehearsed and completely natural. That is how I feel the music should be taught. I get turned off when I see these videos out now, because they always miss the point. It’s not about licks.”

Berrios says he emphasizes this point to his students. “I tell my students that if you want to become a musician, come to my gig and watch me set up the drums. Then watch me play, and afterwards watch me pack up. Then we can talk about anything—boxing, or what food I like. The point is that you’re not just a musician when you’re on stage; you’re a musician twenty-four hours a day! You don’t learn this by watching some guy play licks.” Advertisement

Berrios recently put his own band together featuring himself on drums and percussion, Papo Vazquez on trombone, Mario Rivera on sax, Joe Santiago on bass, Eddie Bobe on vocals and percussion, Pupi Legarreta on flute, violin, and piano, and Greg Jarmon on percussion. Steve half-jokingly describes this band as “a sort of rumba with drumset.” He says he’s looking forward to recording with the group and making some beautiful music. In the meantime, he continues to explore the boundaries of the drumset and to inspire all those who hear his music.