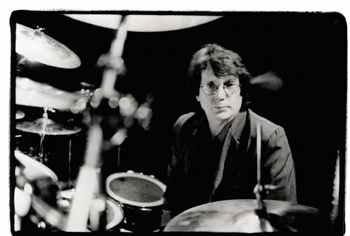

Richie Hayward: The MD Interviews, Part 1

Interview by Robyn Flans

The drum world will never see another Richie Hayward. The longtime Little Feat drummer, who passed away in August, was among the most musically stylish and quietly influential drummers of the classic rock era, equal parts monster technician and old-soul groove master. MD conducted a number of significant interviews with Richie over the years, including his first major interview from March 1988, which we’re posting here. And be sure to watch this space for Richie’s October 1995 cover story.

MD: What got you into music?

MD: What got you into music?

Richie: I was in Ames [Iowa], which was a college town, and there were a few “musos” hanging around. I just kind of gravitated to them, and they taught me a few things. It was the time of the folk thing, and, through that, I discovered the blues. Anything was better than what was going on at the time. I heard Ray Charles on the radio, so I ordered all his old stuff, like records from 1949 on RCA. I really liked it, so I went from there.

MD: What made you start playing music?

Richie: When I was about three, my folks took me to a parade. The bass drum came by, and I felt it in my chest—in my guts. That got me going. Then there was no stopping me; it was all I wanted to do.

Advertisement

MD: Reportedly your parents weren’t crazy about the fact that you were into the drums.

Richie: They weren’t terribly discouraging, but they did find it annoying to have me pounding on things in the basement all the time, while I neglected my studies and was turning into a young hooligan before their very eyes. They thought there were many more acceptable ways for me to fill my hours, but that was all I wanted to do.

MD: How did you get a drumset?

Richie: I mowed lawns and shoveled rocks until I saved enough money to buy this Montgomery Ward drumset for $150. I remember waiting for months for that thing to come in. I was eleven.

MD: How did you learn to play?

Richie: I started pounding on the set while listening to records. I joined the band at school, although I never really liked the discipline part of it. The teacher wasn’t terribly inspiring. An insurance salesman named Jerry Malone, who gave drum lessons, taught me a couple of basic things, like how to set them up and what each foot was supposed to do, and he put me onto some records. That was it as far as lessons. I would hear something and try to figure out how it was done.

Advertisement

MD: Were there particular drummers you dug?

Richie: A drummer named Jack Sperling really knocked me out; he still does. He did some stuff that was just unbelievable. He was one of the first people who used two bass drums and more than two tom-toms, and he played really aggressively. I really liked the way drums just seemed to make everything have its identity.

MD: Were you into double bass?

Richie: No, I never was, but I admired the idea, and Sperling was a pioneer. I never got into double bass myself, because I’ve always had such an affinity for the sounds and innuendos you can play with the hi-hat that I never wanted to take my foot off it and play something else. But I tried to figure out how to do something like double bass with just one.

MD: Can you explain that?

Richie: I don’t really do it well, but I try to do a lot of double kicks and put them in odd places. I do exchanges between the left hand and the right foot instead of between two feet, so if I need a flurry of notes, it’s there, but it’s not necessarily all from the bass drum. The bass drum plays what the second bass drum would be playing, and the right hand plays what the right bass drum would be playing.

Advertisement

MD: Where did your affinity for the hi-hat come from?

Richie: It’s the easiest of the cymbal techniques to control. It seemed like it was necessary to keep that going no matter what else you were playing.

MD: What type of music were you playing along with?

Richie: At the time I was in Iowa, there wasn’t much to choose from. I played my first gig when I was twelve, to a bunch of middle-aged Shriners. We played old standards at their lodge’s New Year’s Eve party. I was younger than most of their children. A couple of years later, as we were starting high school, a couple of friends and I started a rock ’n’ roll band, and we played at fraternities and roller rinks. I just sought out gigs wherever I could find them.

MD: What did you aspire to? What was your goal?

Richie: To get as far as I could, and to play with the best people I could find.

MD: How old were you when you moved from Iowa?

Richie: I was nineteen or twenty. I knew one person in L.A. very, very vaguely, and I stayed with him for a couple of weeks until I got a gig. Then I moved to a little place in Hollywood.

Advertisement

MD: Who was the gig with?

Richie: A band called the Rebels, who were playing in bars. Then I saw an article in the Free Press that said, “Drummer wanted. Must be freaky.” I thought that was weird. Oddly enough, it turned out to be [Little Feat founder] Lowell George, who, at that time, was in a group called the Factory. That was in ’66.

MD: “Must be freaky”? What does that mean?

Richie: I wasn’t sure. I’m still not.

MD: So what was that all about?

Richie: It was a ’60s L.A. band—bell bottoms, big buckles, and sandals. That band had Martin Kibbee [aka Fred Martin], who cowrote a lot of Little Feat songs, on bass. Lowell and I stayed in contact, and Little Feat happened a couple of years later.

MD: You and Lowell just hit it off?

Richie: It was a love/hate thing, but yeah, we pretty much hit it off.

MD: What do you mean by “love/hate”?

Richie: At that time, one of Lowell’s short suits was tact, so if he wanted you to change something you were doing, his suggestion came in the form of near-abusive delivery. The fact that he was usually right made me take it. After a while, it turned into a procedure.

Advertisement

MD: It was obviously musical.

Richie: Yes. It wasn’t personal.

MD: Can you be specific about the exchange that would go on?

Richie: He wanted me to stay more in the groove; he didn’t want me to depart from it to do fills. That’s another way I started to expand this cheating I was explaining earlier. By using my left hand and my right foot to do a fill and staying on the hi-hat, I would try to incorporate a fill without breaking the rhythm and the hi-hat figure.

MD: What kind of music were you playing at that time?

Richie: At that stage, we were really big Howlin’ Wolf fans. The very first Canned Heat band was better than later versions, and we watched them a lot. Frank Zappa was a big influence on us at that time. Lowell was in the Mothers Of Invention for a while.

MD: How did you develop your own playing style? Where did the second-line stuff come from?

Richie: I always loved the Meters, Clifton Chenier, and Professor Longhair.

MD: When did you start getting into that type of music?

Richie: It was back in the ’60s. I had heard it before then, but I didn’t understand what it was. It moves something in me that other music doesn’t quite touch. Lowell helped in figuring it out a lot, too, and vice versa. I just kind of naturally played in that style anyway. We both liked it and wanted to play with that influence. So the songs he wrote began to require that sound, which naturally developed in my style of playing with him for so many years. That influenced his writing, and it snowballed from there.

Advertisement

MD: You were finished with the Factory?

Richie: It finished itself, and then I joined a band called the Fraternity Of Man, which I don’t talk about very often. That was my first and last dabble in political music.

MD: Why?

Richie: Because it was bullshit. Of all things to be called, that band was definitely not a fraternity. There was a lot of dissension, to be quite nice about it. We didn’t get along at all, and we didn’t play terribly well, either. During the time that band was around, Lowell did a stint with the Standells, and then a stint with the Mothers, and then they were both over with by the time the Fraternity Of Man disbanded.

Lowell was back in the picture because he was coming on to the sister of my wife at that time. He married her, and we were hanging out together a lot, so we started Little Feat.

MD: Who came up with the name?

Richie: When Lowell was in the Mothers, Jimmy Carl Black used to point at Lowell’s feet, laugh, and say, “Look at those little feet,” so Lowell decided to name the band Little Feet. Then we came up with the idea of putting the “a” in it. When Lowell was in high school, they called him Triangular Earth Pads or just Earth Pads George because his feet were as wide as they were long.

Advertisement

MD: How did the band evolve from there?

Richie: Zappa’s manager, Herbie Cohen, was helping us financially at that time, and [Little Feat keyboardist] Billy Payne had sent a cassette of himself on piano, wanting to get into the Mothers. Frank already had enough keyboard players, so he turned us on to Billy. We heard him once and said, “This kid is monstrous.” He joined up, and then we got Roy Estrada [later replaced by Ken Gradney], who Lowell had worked with in the Mothers, to play bass. We were old friends; he was there the day I auditioned for the Factory.

MD: Did you primarily play Lowell’s material?

Richie: Yes, and some of it was Billy’s, too.

MD: You have said that the tension in the band provided the creative surge.

Richie: It helped. It kept us from getting too comfortable.

MD: Was it tension between the individuals’ personalities or musical styles?

Richie: It was both, but mainly musical, like little things that one of us would play that some member of the band wouldn’t give him a break about. That player would end up changing and growing as a result of compromising, and after a while of that, we grew together into a thing that was greater than the sum of its parts. We grew into a style that was just built around that group of people. Then the music started to become intuitive; we could almost read each other’s minds while we were playing, and sometimes great things happened.

MD: Can you remember specific things that band members were doing that other members wouldn’t give them a break about?

Richie: [laughs] It was mainly all of them coming down on me. I tend to play too much. I always used to, and still do a little, because I like to hear the drums go crazy. They wanted me to restrain myself a little.

Advertisement

MD: You said great things happened. Like what?

Richie: More often than not they would occur on stage. Some of the strange turnarounds we did were a result of that. Some were mistakes that everybody would cover for. Then we’d hear it back on a cassette of a gig, and it would be better than the real arrangement, so it would get changed to that.

MD: You have also said that the records never came easy. Why?

Richie: There was a drug problem in the band, and it was making a lot of people uptight. Things weren’t quite as smooth as they should have been, so people were getting upset about it, and there were power plays and undermining of credibility as a result of that.

MD: You said Feats Don’t Fail Me Now was an easier album to make. Why?

Richie: That was kind of a reunion. They had actually fired me; they thought I was the reason a lot of things weren’t happening, and that another drummer would be more steady or something.

Advertisement

MD: When was that?

Richie: It was in ’74, during Dixie Chicken. They tried a bunch of other drummers and then called me back. They almost abandoned the band altogether. Then we rehearsed and recorded real fast, where we didn’t have time to nitpick the songs to death. “When The Shit Hits The Fan” and “Tripe Face Boogie” are songs we had been doing live before, and “The Fan” was something we had tried to record two albums before but couldn’t get right because it’s in a lot of very odd time signatures. We recorded that live in the studio, and it came off. It was really a relief.

MD: Usually, when someone has been fired from a situation and then comes back, there’s even more pressure.

Richie: This was the other way around. I think we all learned a little something about it during the time I was away, and it just felt good.

MD: You weren’t anxious about coming back?

Richie: A little bit, but I was also eager. I really liked playing that stuff.

MD: What about that music made you love playing it?

Richie: I loved the eccentricity of it—the fact that we had spent so much time on it that it was like a part of us. We never got tired of playing it, because it was difficult enough to keep us on our toes, and we never played it exactly the same twice. It was a new challenge every day, and it was fun. We’re going to do it again. All of us recently got together to see how it felt.

Advertisement

MD: You guys can’t seem to…

Richie: …leave it alone.

MD: So how did it feel?

Richie: The spark is still there. I really think we’re going to give it a shot. We’re working on a new album, and there’s a lot of record company interest. There are ten new songs written by Billy and Paul, Craig Fuller, and Fred Tackett. It feels really great. We all get along much better now that we’re clean and sober.

MD: What are you going to do without that tension in the group?

Richie: There’s an element that will still be there, I’m sure. It’s just going to be more controlled.

MD: Let’s go through some of the past albums and songs. You cowrote a couple of tunes. How did they come about?

Richie: They developed in different ways. “Mercenary Territory” happened when Bill and I were having similar marital problems, and a few of the lines in there came from the group joking in the bus or something. Then we got together and worked out that 10/4 bit in the middle, so he gave me partial writing on it. All the songs were little bits and pieces that we threw out of other songs and later put together in new contexts.

MD: How did “Day At The Dog Races” come about?

Richie: It was a jam we used to warm up to a lot at soundchecks, in the studio, or at rehearsals. It just grew into the sections it did after we played it for a while. We all contributed to that song equally.

Advertisement

MD: Did the band write in the studio, or did Lowell or someone else just bring completed songs in?

Richie: He didn’t just bring them in; we definitely would have a lot of influence on them. Rather than arguing about who wrote what part, we shared the publishing evenly. The writer got his half, and the band split the publishing evenly. It was very democratic.

MD: Was the creative input democratic as well?

Richie: Pretty much. If it was a valid idea, we tried it. If it worked, we used it. There were very few egos in the way of that. It was real special that way.

MD: How did “Dixie Chicken” come to be?

Richie: Lowell had that specific feel in mind, so there wasn’t a whole lot of changing done, except that Billy came up with that great piano part. I enjoyed playing it. The basic feel was pretty much what Lowell had in mind, but the way it was done and the fills weren’t.

Advertisement

MD: Are there songs you can think of where something you played might have had more influence over how the song turned out? For instance, did the arrangement or feel you were laying down dictate the way a particular song ended up being played?

Richie: “Fat Man” was like that in a way. We used to just jam on that feel a lot, for about three years before we recorded it. The odd 2/4 bars in “Cold Cold Cold” came about in a strange way. Lowell had been playing with his drum machine at home. At that time, drum machines were very primitive. It was just a little red box with two knobs on it. He had the basic pattern repeated over and over again, and he played it with just himself and a little amplifier on a cassette at home. Somehow he edited the cassette, put it on a 16-track tape, and had me overdub drums. It’s funny because this drum part was turned around a couple of times due to the way he cut it together to fit. He wanted me to copy it and throw in fills. That’s on Sailin’ Shoes. On the first part you can hear the machine.

MD: On the Little Feat album there was a song, “Willin’,” without drums.

Richie: That was the publishing demo that Lowell did with Ry Cooder. Lowell was in one studio with Van Dyke Parks, and Ry was playing down the hall. They put it on the Little Feat record, but then we decided that, since the whole band played it live, we would re-cut it on Sailin’ Shoes.

MD: And also on the live album, Waiting For Columbus?

Richie: That’s my favorite because it shows what we did live with the stuff from the studio records. It’s not even from a real good night. It’s not a bad night, either, although there were some things that were done on other nights that I wish were on record. Some of Billy’s solos were incredible.

Advertisement

MD: Was there one person you played off more than the others?

Richie: No, it changed from song to song and era to era. I imagine I was most interested in Lowell’s vocals; he put things together in such an eccentric way.

MD: What do you mean by that?

Richie: He didn’t use any normal formula for writing, which I found really refreshing.

MD: The band never formally broke up, right?

Richie: I guess you could say that. Starting in 1979, when Lowell died, we took a seven-year break. I was in traction at the time from a motorcycle accident.

MD: Aside from the loss of a friend, did you feel your musical identity was gone?

Richie: I felt an awfully big change coming on, but I couldn’t let it be the end of everything. It took a couple of years to pick up the pieces, but I feel great now.

Advertisement

MD: That kind of intuitive musical experience must be a tough act to follow.

Richie: I think that’s the main carrot we’re chasing as we’re getting it back together now; to get that feeling—that spontaneity—back and make it fun again. We might have fought like cats and dogs right before or just after a gig, but we were brothers while we were playing. We could give each other a real hard time, but if anybody else tried to give any one of us a hard time, he had to deal with six others, like Italian brothers.

MD: Weren’t you guys in the middle of a record when Lowell died?

Richie: Yes. That record [Down On The Farm] was put on ice for two reasons. First, Lowell was going on the road promoting his solo album; second, I had my accident. I was six months in traction and five months in a body cast. They delayed finishing the album until I got out of the hospital, and Lowell was gone by then, so the rest of us finished up the background vocals. Seventy-nine was not my favorite year.

MD: Were your limbs in jeopardy?

Richie: My right leg was. The doctors said they might have to take it, but I wouldn’t let them. That’s why I was laid up so long, to keep it. It was worth it. I don’t want to take this interview into a dark corner, but that was the dark corner of my whole career.

Advertisement

MD: With a year away from the drums, what did you do to get back into shape?

Richie: I bluffed a lot. Right after I got out of the cast, I got a call from Glyn Johns wanting to know if I could do a tour with Joan Armatrading, and he asked if I could play. I said, “Sure, sure.” I had just gotten the cast off, and I hadn’t played yet. I went on the tour; six months on the road, 144 gigs, almost every night. So I got it back that way.

MD: You did an album with Joan Armatrading?

Richie: Right. That was before the accident. I did one four-week tour with her, and they recorded it live. It’s called Steppin’ Out, and it came out in ’79. It was interesting because I had to learn twenty songs in two weeks. I was running on fear, but it worked out okay. They recorded three nights of it, but because of technical problems I think only one night came out. The album didn’t sell too well, but it has some moments on it.

MD: Do you remember what you enjoyed playing the most?

Richie: A song called “Barefoot And Pregnant” was my favorite. It was fun to play because it was more jazz than I was used to. It wasn’t a great time for me, though, because I was a very bitter guy then and I wasn’t very nice.

Advertisement

MD: You had just come through an awful time.

Richie: But I overreacted. Sorry, guys.

MD: Were you angry about Lowell?

Richie: Yes, I was angry about everything.

MD: How did you work through that?

Richie: I guess I just lived through it and came out the other side. I feel completely different about things now than I did then. Things are much rosier.

MD: What happened after you finished playing with Armatrading?

Richie: Not much; I was just doing little things here and there. Then Robert Plant called me out of the blue, I played on his album Shaken ’N’ Stirred, and things got better.

MD: There are some interesting things on that record. Two songs in particular seemed like lots of fun, “Hip To Hoo” and “Kallalou Kallalou.”

Richie: On “Hip To Hoo” I was experimenting with Simmons drums. That album was the first time I used them.

MD: What did you think?

Richie: They were a nice addition to the kit, but at that time technology wasn’t what it is now. There was no way they were going to replace a kit. I hated electronics at first because they were replacing drummers. I felt threatened, and rightfully so.

Advertisement

MD: How do you feel about electronics now?

Richie: Now I’ve learned to appreciate them for what they can do. I enjoy playing with them, like programming percussion parts and then playing real drums with them.

MD: It’s hard to imagine electronic drums in the Little Feat context. Maybe that’s narrow thinking.

Richie: I’m equally narrow in that respect. Most of that stuff couldn’t have been done the same on electronic drums.

MD: How would you do “Dixie Chicken” on Simmons?

Richie: Well, gee, that’s something I probably wouldn’t do. But who’s to say? Some of these new electronic drums sound like real drums. I think using pads with the real drums, as opposed to replacing them, is the answer. With Robert I used five Simmons pads and five real tom-toms, so it just gave me more stuff to use instead of an “instead of” situation.

Advertisement

MD: How did you feel about Robert’s music? It definitely was more high-tech than you were used to.

Richie: It was interesting. I loved it and had a good time playing his songs. We wrote that music all together, working it up from nothing into what it was. We spent months in this barn called Talocher Farm—an old country inn that had been converted from a sixteenth-century stone farm. There was an old hollow oak tree that King George was reputed to have hidden in during the civil war. It was great. We went up there with an 8-track and a small board in a trailer porta-van. We just played with the ideas until we developed the arrangements.

MD: Plant called you up out of the blue, but had the other members been with him before?

Richie: They had been together for about three years before that and had done two albums with him already.

MD: You were the newcomer.

Richie: Yes, and the only American. It was neat. I moved there and stayed for a few years.

MD: What about road work with Plant?

Richie: I toured America, Canada, Australia, England, Japan, and Hong Kong.

MD: What was that like?

Richie: I had a great time. We had the best sound guy I have ever worked with, Benji Lefevre. He had been with Robert since Zeppelin times.

MD: Having had Little Feat as such a large chunk of your life, was it hard to replace it?

Richie: The way I dealt with that, and still do, is by saying to myself, That was then. To try to replace that would mean ignoring the future. In order to handle what was to come, I had to be prepared for it. Now I’m really eager. That’s why I’m taking an interest in electronics and in other styles of music. I have a wider taste in music than I used to. There are a lot of different things I enjoy doing. Maybe something different, but equally intense, is in store.

MD: That’s a good attitude.

Richie: It’s the only one I can live with.

MD: I’m sure it took a while to get to that attitude, though.

Richie: Oh yes, and it’s a hard attitude to keep, but most of the time it prevails.

MD: You’re doing some sessions. Are you mostly interested in playing live or in recording?

Richie: I would have to say both, equally. I am very interested in recording, although that hasn’t happened as much as I would like. I feel that’s going to change, though.

Advertisement

MD: Do you feel there’s a difference between recording and playing live?

Richie: Yes. When you’re recording, you have to concentrate on the details. You have to think about getting everything just right, just one time. It’s not like live, where you can try something new, and you get to play the song sixty times. After the recording, when you go on the road with it, you can expand it from there, but on the recording you have to zero in on the concept of the tune and accurately interpret it on the spot. There’s much less room for error.

MD: You said before that you’re getting into other styles of music. You have such a definite style.

Richie: I find that kind of hard to break, too. We tend to do what we know instead of trying something new. I’m trying to use this time to expand and grow, and to try on new hats.

MD: How would you describe your style?

Richie: It’s real American with second-line and jazz overtones. As much as I like the subtleties of jazz, I also love to bash. So I try to combine all those things.

Advertisement

MD: Can you recall some of your favorite tunes to play on?

Richie: “Gringo” is one of them. It’s on the Hoy-Hoy! album. David Sanborn is playing on it, and it’s more of a jazz thing.

MD: Did you actually woodshed jazz when you were a kid?

Richie: Yes, and I really loved Steely Dan records. That’s some of my favorite stuff. That’s one gig I’ve always wanted to do.

MD: They make drummers crazy, though.

Richie: Some things are worth going a little crazy for; some things are not. “The Fan” was really fun because it was difficult. So was “Fat Man” and most of the songs on the live record. “Dog Races” was fun because it’s in six and it’s unusual, and I kind of got to turn things inside out.

MD: Where did you learn to play odd times?

Richie: I think it came from Lowell. He had this interest in Indian music, and he took some lessons from Ravi Shankar back in the ’60s. Shankar taught him that there is life outside of 4/4 time, so he brought that into the group. He taught me a lot about how to count it, and we played it until we got it right. I really grew to enjoy it a lot. It’s fun to try to be free in seven time and to play as naturally as if it were four.

MD: Was it difficult to learn?

Richie: I really didn’t find it that difficult. It was just more of what I was already doing, but just a little different approach. It’s cut into twos and threes. You cut up a 4/4 measure that way anyway, so to add a couple of little groupings of one or two or three to the pattern is natural after a while.

Advertisement

MD: How does one expand one’s style?

Richie: I try not to close my mind to things that I haven’t heard before. I find I learn the most about music if I don’t try to criticize it or form an opinion about it. I just allow myself to react. I’ve learned a little something from every drummer I’ve ever seen, good or bad. There’s always something there to pick up—maybe something not to do.

MD: Could you give tips for playing a great second-line feel?

Richie: I don’t have any way to put that into words. Listen to Ziggy [Modeliste]. He’s one of my all-time heroes. He’s brilliant with that stuff.

MD: What are you listening to these days?

Richie: I really like what people like Peter Gabriel are doing with different ways of playing rhythm and their use of electronics, which end up sounding like African drums. I find that really exciting. That’s what I mean by way of incorporating the old and new. Peter is really a leader in that. I hate to say it, but some of Phil Collins’ music is like that, too.

Advertisement

MD: Why do you hate to say it?

Richie: [laughs] Because he’s everywhere. I like a lot of stuff that’s happening now. Bruce Hornsby is really good. To actually hear a piano again is great. I still listen to Steely Dan records a lot. The first Rickie Lee Jones album is great, too. I like what the Pretenders are doing. I like Eric Clapton, Dire Straits, and some of the old Police records.

MD: How did the recent Warren Zevon tour come about for you?

Richie: Kenny Gradney had a line on that gig; we auditioned and got the gig.

MD: What did you have to do at the audition?

Richie: I just played a couple of songs.

MD: What is his music like to play?

Richie: It is simple, but fun, and Warren is really a nice man to work with. I’m singing with him, too, so that’s a lot of fun.

MD: You sang with Little Feat.

Richie: Right. I sang all the high parts.

MD: What do you have to think about when you play and sing at the same time?

Richie: You have to concentrate most on the singing because the drumming kind of takes care of itself. If it’s a very difficult drum part, I can’t sing, though.

MD: In Little Feat you were doing all this odd-time material and singing.

Richie: But that stuff was well rehearsed. I had played it so much.

MD: Can it be difficult to sing and play at the same time?

Richie: It can be, but I think the main thing is not to think about it too much, or else you get tangled up. It’s just an extension of playing. It’s just another appendage, so to speak, so it’s just an added thing to the pattern. It’s just one more additional requirement, and you think about it all equally. I’m not a virtuoso singer; I just have a voice that blends well in the background. It’s fun to pull it out of mothballs with Zevon, because I haven’t done that in seven or eight years. He and I are the only male singers on this tour, and there’s a woman who plays keyboards and sings background.

Advertisement

MD: So you’re doing all the harmony parts?

Richie: Yes, I’m doing all the Don Henley parts.

MD: Did you have to sing in the audition?

Richie: No, he didn’t know that I could sing until afterwards, when I volunteered.

MD: What are your musical and personal goals?

Richie: I just want to be as good as I possibly can and go as far with my drumming as I can. I would like to play a lot of different types of music.

MD: What’s your favorite music to play?

Richie: I like rock ’n’ roll with a jazz kind of slant to it. But I like a variety of stuff. Little Feat was ideal for me because it was all kinds of different things, like Cajun and the second line, jazz, country, and heavy rock.

MD: What’s your expectation of the group getting back together?

Richie: From what I’ve seen, the records are still in the stores, there are five or six CDs of the band now, and it’s still holding up after nine years. It looks really good if we can get the chemistry cooking like it was, which I think we can.

MD: Ideally, would you like that to be the medium that takes you where you want to go?

Richie: I would like that to be the center of it, but I’d like to be free to do other things as well. There’s no end to how far I want to go, and I feel like I’m just starting to discover myself again.

Advertisement

READ PART 2 OF THE INTERVIEW HERE.