Robert Wyatt: 2007 Web Exclusive Interview

by Adam Budofsky

by Adam Budofsky

Since leaving the groundbreaking British psychedelic band Soft Machine in 1971, Robert Wyatt has released a succession of remarkable solo albums filled with artfulness and surprise. His latest, Comicopera, is a worldly, three-part meditation on modern profundities. MD chatted with the always gracious musician to learn what’s fueling his art these days.

MD: Congratulations on your new album, Robert. I’m always happy to recommend your latest release to newcomers, though that isn’t always the case with other artists.

Robert: People think growing older is a bad thing, but what I like about it is, you get time to learn more about what works and what doesn’t, and fine-tune it.

MD: I suppose we get used to people having their “formulas.”

Robert: Yeah, I wish I had one of those. [laughs] God, life would be so much easier. Every time I go into the studio, I think, How on earth do you do this? I start to write a tune and think, What do I know about writing a tune?

MD: Do you eventually find something that you latch onto?

Robert: Well, I’ve got triggering devices, that’s another thing you learn as you get older. My current device is sort of “karaoke cornet playing” with old jazz records. Of course I can’t really play it like a craftsman, but I can pick up notes that I might sing. I can’t play bebop speeds, but I find classics like Gershwin tunes, Nat King Cole, Sarah Vaughan—things that I didn’t even listen to when I was younger—and just find other appropriate notes. This works well for lubricating the inside of my head, gives me lift-off. It’s a way of finding lots of different melodic threads off of one chord sequence. I still get astonished at how much Sonny Rollins can get out of one chord sequence. Now, I’m not a jazz soloist, but it seems to me a good way to start out finding tunes. I know some people start by setting up a beat on a drum machine or something, but I find that gets me absolutely nowhere—partly because I don’t hear things in beats. I still hear things in an anachronistic ride cymbal swing thing. Advertisement

MD: As you’re improvising melodies, I imagine some kind of rhythmic element is already there from the beginning.

Robert: I suppose that’s right. That element of jazz 4/4, which is in fact a 12/8 with a triplet feel, is a basic rhythm for me. Even if I’m working on something with more of a New Orleans, Bo Diddley thing, I won’t do it like Eddie Cochran or whoever—though I love the way he’d do it—but I like it when it’s more overlaid with a swing thing, that sort of feel.

MD: That’s the beauty of music from New Orleans, there are so many possible directions….

Robert: Yeah, you can take it anywhere. It’s such a wonderful way to start out. When I’m looking for melodic lines, though, I need some sense of a harmonic landscape.

MD: There was an interesting thing that happened when I first saw your new album’s title. Maybe I had in the back of my mind your past references to Latin music, but I read it as “Comi-copera,” like some Spanish word I was unfamiliar with, rather than Comic-opera. Has anyone else made that mistake?

Robert: No, it’s not a mistake. One of the things I like about putting that word together is you can sort of make various other words out of it. I’m very happy when that happens. The album isn’t an academic exercise in modern comic opera, though it has allusions to the genre. And the word “pera” means “pear,” the fruit, so to be “a funny pear” sets up a whole other, rather nice kind of meaning. Advertisement

MD: You were talking about musical trigger points. How about lyrically?

Robert: I tend to have more musical ideas than lyrical ones in terms of what I’d put on a record. So sometimes I’ll have pieces lying around dormant because I’ll only have one element or the other, and there’s no way I can artificially put some words to music or some piece of music to words. Sometimes I’ll even use other people’s tunes. I begin this record with a tune by Anja Garbarek and end it with a song by Carlos Puebla, and bits and pieces in between are based on a tune by Brian Eno, beautiful stuff that he had knocking around but didn’t know what to do with. For the words, I just have to strike lucky, and I don’t often, which is why having my wife, Alfie, around is good. There’s a lot of imagery in what she does, sometimes quite direct, sometimes indirect. But she sort of comes to my rescue with the words. We’ve known each other long enough where she knows what would be convincing for me to sing.

MD: In my mind your songs often seam to have been prompted by some conversation you’ve had with her.

Robert: That’s exactly right, indeed they are, to the extent that with some songs, I don’t know which one of us came up with which line. But on the whole it sort of pans out…with this record, for instance, in the first third of it, apart from the opening Anja Garbarek song, the lyrics are Alfie’s, then they’re mostly mine, and then it ends with this song “Out of the Blue,” which is Alfie’s again. Then I go abroad and do songs from all over the place—by a group of Italian musicians, by Garcia Lorca, by Carlos Puebla…. But that was just because it’s great fun singing in other languages, and I like pretending I’m not from England. It makes me feel less, um, embarrassed. [laughs] English-speaking people have these hubristic moments of ruling the world, and I get so embarrassed by that stuff.

MD: Do you see yourself as the leader of your projects?

Robert: I don’t know if leader is the right word. It’s more like, “The buck stops here.” I have to take responsibility in the end for how it’s all put together. And the other musicians are there, God bless them, to help me get my songs out right. It’s only for a few days in a year. It doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll be in a group on the road together—in fact, it’s very unlikely. I can’t imagine Brian Eno in a jazz band, or Paul Weller playing guitar with Brian Eno. So it’s kind of an imaginary get-together, people with different elements that are important to me. Advertisement

But I have thought a lot about the issue of musical leadership, because I’ve been both a band member and a sort of conductor of the band. I had this group called Matching Mole [Robert’s short-lived post–Soft Machine band, which put out two albums in 1972]. A little record company called Hux has recently found some BBC stuff we’d done that I forgot about. The CD is called Matching Mole on the Radio. Anyway, I remember that business of having that role as a drummer and a leader, and there’s one obvious problem, and that’s too many drum solos. [laughs] It’s one way to be, but I was always concerned as a drummer with the fact that we’re in the engine room, and that whatever I was playing was relying on the melodic gifts and inventiveness of the other musicians. It was simply my job to keep it on the boil. I found this an interesting thing to do. I think of the role as that of an audible conductor—organizing the pace and the dynamics in such a way as to keep it alive and flowing.

The drummer/leader I’ve been listening to recently that’s most effective is Kenny Clarke. I got a box set of his—it’s sort of classic ’50s hard bop—and he’s such a discreet sounding drummer that most people would think he was kind of a nightclub drummer: keeps time, uses brushes…. He might be better known in Europe, because he left the States in the mid-’50s and came to work in France, where he became a central figure in the French jazz scene, of course along with Bud Powell. With Kenny, you have to go through hours of stuff to guess that the drummer is the leader. But there is something in common, which is that everything just moves with such a sweet groove. You can hear that everyone can relax, that he’ll take care of them. And it’s a lovely feeling. I get that, funny enough, with Blakey. There’s a lovely Hank Mobley record I’ve got from I suppose the late ’50s, and he’s such a wonderful accompanist. He’s not very complex for a modern jazz drummer, he just sort of swings. But the way he changes the pace throughout the solo, and gathers it together, and helps the next soloist get off the ground—it’s just so beautiful, such a high level of generous craftsmanship.

MD: There are Elvin records where he’s not “being Elvin” so much, too.

Robert: Yes. We’re talking about helping the other musicians get off the ground. That was the job: Get off the ground, and stay off the ground. Of course, it’s not the only role. Tony Williams played alongside people, and that’s pretty good too. Advertisement

A very underestimated drummer of my era, who I shared a lot with and learned a lot from, was Mitch Mitchell with Jimi Hendrix. I watched them night after night for most of 1968. [Soft Machine opened for the Jimi Hendrix Experience on their American tours.] I knew Mitch before he was with the Experience. He was the drummer with a really good R&B band in England called Georgie Fame & the Blue Flames. That was basically jazz musicians playing a kind of big band blues, closer to the Jimmy Smith era of danceable jazz. And Mitch negotiated going through that to working with Hendrix with great aplomb and great inventiveness. A lot of people thought Jimi should have had a heavier drummer, and eventually he did with Buddy Miles. But I thought Mitch was the most appropriate because he was so fluid. From jazz he got this fluidity and speed of thought.

MD: The changes in popular music at that time—and you were right in the middle of that—seem so extreme from a vantage point in 2007. I wonder, if Hendrix had stayed alive, where he would have been musically even four or five years after Band of Gypsys. What would the drummer in that band…

Robert: …What would he have to be able to do, yeah. But there was the sense that people made mistakes and knew it. I know Noel Redding, the bass player in the Experience, said that sometimes when Mitch and Jimi were really flying, he actually didn’t know where the beat was and had to stop playing. This reminds me of Coltrane. He’d go off with Elvin where the piano and bass couldn’t follow, and nobody is more secure with the beat than McCoy Tyner and Jimmy Garrison. But in the end they’d just leave Coltrane and Elvin to go to it. So there’s a perfectly respectable antecedent to what Jimi and Mitch were doing. Advertisement

MD: You can almost hear John Cage saying, “That’s fine; it’s good that you were confused and had to stop.”

Robert: [laughs] Yes, right! I mean, these are the moments where you have to think fast and where a lot of creativity can come through. “You didn’t expect this to happen…so what are you gonna do now? Come up with something quick.”

MD: Or if not, just chill out.

Robert: That’s right, sit this one out. I used to do that a lot. I’d be playing and think, “You know, this would sound really good without the drums,” and I’d stop playing. Eventually the musicians around me would get used to the fact that I might well do this [laughs], but in a sense it was a compliment to them.

MD: I’ve got twenty CDs by drummer/leaders here at my desk, and I would bet there aren’t four songs total without drums on them.

Robert: Yeah, I won’t use them unless I think they’re an integral part of the song. I mean, when I’m recording I get a whole pile of stuff on, but then I strip it away to what I need to keep the thing going. Like on the second track, “Just As You Are,” I have a really upfront ride cymbal thing going. But then there’s other songs, like “You You.” I tried to add an appropriate drum thing to that, and to me it just made it a bit more pedestrian, a bit more obvious…a bit more normal. I thought, “No, I’ll just leave it with the bass guitar strumming along, that’ll do it.” Advertisement

MD: One of the nice things about coming to a new album of yours is not having a preconception of what the arrangements are going to be like on each song. I love that you might be thinking, “Well, we don’t need red in this picture.”

Robert: Absolutely. I took this to an extreme at one point. There’s a song on there called “Be Serious,” which is about being envious of people who have a religion. Paul Weller did several tracks of guitar, and I liked what he did so much that I took nearly everything else away except the voice, Paul’s guitar patterns, and a cymbal. That’s all the song needed, all of the information was there. Some of my favorite moments in recording are in the editing. For instance, the vibes duet toward the end—Orphy Robinson double tracked himself, and we treated one of the tracks and left the other alone—but this originally had a rhythm section accompaniment to it, a 7/4 figure. We took everything away to hear what Orphy was doing, and I really liked the fact that the time seems uncertain, and it gathers momentum and then sort of spreads and comes back again…. It seemed much more interesting rhythmically than when it had the rhythm section in the mix. It was a difficult moment because I’d really liked what I’d played on drums. But I thought, “Robert, that’s not the point.” [laughs] The point is, what works here? I’d done my job as a drummer, which was to set the pace for him to play to. He’d done that, and now he didn’t need me anymore.

MD: The process of elimination doesn’t seem to be thought of enough. We’re always thinking, “What can I add here, what kind of harmonies can go here…”?

Robert: I do have dense moments sometimes, when I really layer it on. But I really mean to do that then. It just depends on the song. The only difficulty I used to have with jazz musicians is that they would wait for their moment where they could do their thing, and what I really want is musicians who can play as well as jazz musicians, but think in terms of, What does this song really need? And that’s why I’m so grateful to the musicians; that’s why I used the same ones as I did on the last record—Gilad Atzmon on reeds, Yaron Stavi on bass, Annie Whitehead on trombone, for instance. Technically they’re really shit-hot, but they only play what’s appropriate. I’m so grateful for that. It’s taken years to find these people. Advertisement

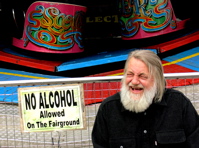

Photo by Alfreda Benge.