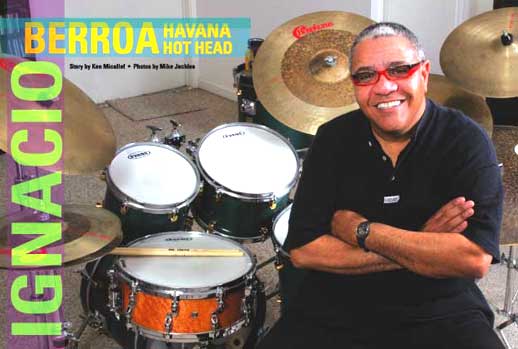

Ignacio Berroa – Havana Hot Head

by Ken Micallef

Imagine growing up in a country where playing music is illegal, where practicing religion can get you yanked out of your home in the middle of the night, and where the only available drum instructor is some moldy Russian guy with enough ear hair to start a small forest. During the Cuban communist revolution of 1959, citizens of the country that gave us Chano Pozo and the Buena Vista Social Club suffered much, but their spirit and resilient music never faltered.

“We listened to The Beatles and Art Blakey records,” says Ignacio Berroa, recalling his teenage years in Havana. “Those were records that people had in spite of the Cuban revolution. Some of my peers’ parents liked jazz and they had those records. But it wasn’t easy. My generation had it very, very hard. It was almost prohibited in those years to play jazz due to the political situation between Cuba and the United States. Everything from the US government was deemed a conspiracy against the Cuban ideology.”

Like the great conga player Chano Pozo before him, Ignacio Berroa brought the rhythmic traditions of Cuba to bear on American jazz. The originator of the songo to US shores, Ignacio arrived in New York City from Havana in 1980, joined Dizzy Gillespie’s group a year later, and has been a first-call musician ever since. Advertisement

Unlike most musicians whose bios are typically filled with a history of private study, small-group performances, college gigs, and professional struggle, Ignacio was a star in his native Cuba, but gave it all up to fulfill his dreams of playing US jazz. Even in Cuba, though surrounded by a wealth of indigenous rhythms, Ignacio sought out the jazz and pop music he loved. Trained in rigorous Russian classical methods, he could sight-read anything, but was not allowed to have his own drumset. He could memorize and sing Mozart’s “Symphony No. 40” over a steaming 6/8 montuno, but songs by Miles Davis and The Beatles were prohibited.

This unusual dichotomy, coupled with his early years as a violinist, led to a drumming style based in Cuban folkloric tradition but fired by American jazz and pop. Ignacio was among the first of what is now recognized as a new wave of Cuban musicians that includes Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Danilo Perez, Paquito D’Rivera, Daniel Ponce, Andy and Gerry Gonzalez, Ed Simon, and many more. Ignacio’s work with these musicians as well as McCoy Tyner, Chick Corea, Kip Hanrahan, Hilton Ruiz, Dizzy Gillespie, Jamaladeen Tacuma, Giovanni Hidalgo, and Charlie Haden has culminated in his first solo album, Codes.

“This work comes with a deeper and more complex musical nuance than what Latin jazz audiences are used to,” Ignacio states in the liner notes. “It comes with codes that coexist and converge in harmony, with absolute respect for each other. Advertisement

“I believe when playing,” he continues, “we should pay respect to all musical styles, call it jazz, Afro-Cuban, Latin-jazz, or even so-called Brazilian-jazz. Respect and devotion to the style’s true origin and meaning is far more important than playing it just because it might be in vogue.”

Like a Cuban Roy Haynes, Ignacio’s drumming sizzles, sparks, and pops, easily flowing from difficult sons, cascaras, and rumbas to spacious swing. Codes mixes styles, locales, and rhythms with a nod to tradition, but with an eye trained on the future. Joined by a mighty band including John Patitucci, Ed Simon, Armando Goia, and Giovanni Hidalgo, Ignacio is positively gleeful slapping a roller coaster 6/8 feel on Chick Corea’s “Matrix,” or crisscrossing impossibly dense

Afro-Cuban rhythms for Wayne Shorter’s “Pinocchio.” Like all great Cuban drummers, Ignacio’s rhythms kick with an almost animalistic power, but there’s also a sense of grace, a lightness to his playing that results in an easy, dance-like pulse. Advertisement

Dizzy Gillespie once said, “Ignacio Berroa is the only Latin drummer in the world, in the history of American music, who knows both worlds–his native Afro-Cuban as well as jazz.” Here is that same Ignacio Berroa, live from his home in Miami, his music detailed, his drumming de-coded.

MD: On, it seems you blend Brazilian, jazz, songo, son, cascara, Yoruban, and everything else. Chick Corea’s “Matrix” is played in 6/8, which is very unusual. The track is very syncopated, and it really dances.

Ignacio: Regarding my conception for picking the tunes for the album, I wanted to play ones that aren’t commonly played in the standard repertoire. And I wanted to pay tribute to the musicians who influenced me. I always loved “Matrix.” I thought it would be more interesting to play it in 6/8 than go into a jazz rhythm. Advertisement

MD: It sounds like you avoid playing the bass drum on the downbeat of the 6/8 pattern. Does that give it more of a dance feel?

Ignacio: Yeah. For the 6/8, for those people who aren’t used to that style of music, the main thing is the clave. [Berroa sings clave rhythm over melody.] We rely on the clave; we don’t rely on the downbeat all the time. That’s natural for us.

I sent the album to Chick, and he said he didn’t realize that I was playing 6/8 until I began the solo. We don’t play the downbeat to make it more danceable or not. It’s like when people ask me, “Are you thinking clave when you play straight-ahead”? No. When I’m playing straight-ahead, that’s all I’m thinking about. Clave is implied. It’s in my blood, so I don’t think about it.

MD: Where do you see the future regarding jazz and Afro-Cuban music?

Ignacio: My goal is for everyone to stop the stereotyping of musicians: if you’re a Latino, you should play Latin music; If you play one style of music, you can’t play anything else. All of that is wrong. I want everybody to know that in the same way that we live together on this planet, we should be able to play every style of music and mix it up and see what happens. Advertisement

In a sense, what I’m doing now is what Dizzy Gillespie used to do many years ago. Many people thought that Dizzy was crazy when he added Chano Pozo to his big band and began blending Afro-Cuban with the jazz tradition. I’m just keeping that alive and taking it to another level. I hope that in the future everybody will absorb all music.