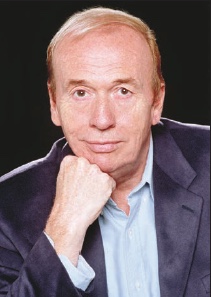

Geoff Emerick: The Beatles’ Studio Ground-Breaker

This is a re-post of Modern Drummer’s interview with Geoff Emerick, who passed away this week. It originally ran in the August, 2006 issue.

by Billy Amendola

As the recording engineer on some of the Beatles’ greatest works, Geoff Emerick set a new standard for the way albums—and drums in particular—are recorded. Geoff’s story is documented in his recently released book, Here, There And Everywhere: My Life Recording The Music Of The Beatles.

Geoff started working at Abbey Road Studios in 1962, as a fifteen-year-old disc cutter. He quickly graduated to the position of assistant to Beatle engineer Norman Smith. When Smith moved to EMI Records to become a producer in 1966, Geoff was promoted to engineer, working alongside producer George Martin and the band that was changing the nature of popular music.

Starting with Revolver, and progressing through Sgt. Pepper, The Beatles (“The White Album'”), and Abbey Road, Geoff took engineering technology to a new level. He introduced techniques that included close-miking Ringo’s drums, as well as removing bottom drumheads and placing the microphones inside the drums. In doing so, he established methods that most engineers still use to record drums today. Sgt. Pepper earned Geoff a Grammy for Best-Engineered Record, and is widely regarded as the greatest rock record ever made. Advertisement

As if his work with The Beatles weren’t enough to make him a legendary musical figure, Geoff also engineered or produced records for Badfinger, America, Robin Trower, The Zombies, Paul McCartney, Gino Vannelli, Art Garfunkel, and Elvis Costello. Yet when MD spoke with Geoff, we found him to be a remarkably down-to-earth gentleman who insists he doesn’t quite understand what all the fuss is about; he’s happy just to do what he does for a living. Luckily for music fans the world over, he just happens to be great at it.

MD: When we interviewed Ringo in the November ’05 MD, we asked him about drum mics and positioning for the Beatles recordings. He said that neither he nor George Martin could remember any of that “technical stuff.”

Geoff: We never really took notes about how things were done. In the early days, around Revolver, we were still on 4-track, so I think: it was basically one overhead, a snare mic, a bass drum mic, and a hi-hat mic. Later I started to close-mike the toms, and I’d do a pre-mix—putting four of the mics onto a premix and then onto one fader, because we only bad eight inputs on the mixing console. Advertisement

MD: So you didn’t have the choice to mike the drums on top and bottom.

Geoff: No. I think I started to do that for Abbey Road. And I think: that was the first time we mixed the drums in stereo, because we now had eight tracks to work with.

MD: What made you think of removing the bottom drumheads to put the mics inside the drums?

Geoff: I love drums, and I wanted them to have more impact. Prior to that point they were sort of wishy-washy, or the bass drum was in the distance with the snare. It was a matter of figuring out how we could get the sound of the drumkit that we were hearing in the studio onto the record.

MD: Do you recall what mics you were using at that time?

Geoff: I believe I was using ribbon mics made back then by the BBC, and now made by a company called Cole-4038s. I put a 56 condenser under the snare, with a D19 on top. Sometimes I’d take the bottom skins off the toms to give them a bit of air, and put a D19 inside them.

It was important to capture the impact, because sometimes even though drums are loud, they can sound small. Ringo really laid into them-though I don’t mean thrashing. He had great control of the way his sticks would land on the drums. It was like all his energy would go into those drumsticks. I remember looking around Ringo’s kit after everyone had gone home, and it would be littered with chips of wood from his drumsticks. Advertisement

MD: Once Ringo’s drums were set up for recording, did they stay set up that way?

Geoff: Yes, we never moved them. And he would always lay a soft pack of cigarettes on the snare drum. We tried something else once, and it didn’t have the same sound. Sometimes we used tea towels over the toms and snare to get a deader sound.

MD: Whose idea was it to hit the three solo bass drum beats right before the chorus on “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds”?

Geoff: I don’t recall whose idea it was, but I believe that’s a floor tom, not a bass drum.

MD: I read somewhere that the drums for “Something” were recorded at a fast speed, and then slowed down to give the toms more bottom. True or false?

Geoff: False. They’re played naturally. And I’m sure I had the bottom skins off the toms.

Remember, though, that Abbey Road was the first record on which we used a transistorized mixing console. I couldn’t get the same impact from the snare or the bass drum. Had Abbey Road been recorded through a tube desk, the drums would have been a lot punchier on the original rhythm tracks and the overdubs, and it would have been a slightly different-sounding album.

MD: How do you like to record drums nowadays?

Geoff: I’ll generally mike the snare on top and bottom, and the toms from the top. But that could depend on who the drummer is. A lot of players don’t like to remove the front heads on their bass drums. Instead, they have a hole cut out. You get a tremendous blast of air while you’re trying to capture the boom of the drum through that little hole. I still prefer to take the front drumhead off. Advertisement

MD: Do you prefer to record the drums in the open or isolated?

Geoff: It depends on what we’re after. But if you’re going to record drums open, you really need a big room for ambience.

The drums are one instrument made up of several components. That’s why I hate it when they’re spread in a stereo picture. I find it distracting to hear one drum on one side and another on the other…unless you’re going for an effect. So I’ll wedge them into the middle of the stereo field. I think that gives them more impact.

MD: Do you record the drums dry and add effects later?

Geoff: Yes—unless I want a quick drum sound, and then I’ll run it mono through the Fairchild. That was basically how we did Revolver.

MD: You’ll always hear engineers say, “It’s the player way more than the instrument. “True?

Geoff: Of course. And it’s funny that a lot of people still don’t understand that. The joke in every studio was, “Can you make my drums sound like John Bonham’s?” And the reply was, “Sure. Let’s ring him up and see if we can get him down here.” [laughs]

MD: What drummers besides Ringo have impressed you?

Geoff: I love Steve Gadd. I worked with him on Paul McCartney’s Pipes Of Peace and Tug Of War and on an Art Garfunkel record. He’s brilliant, the best! I also enjoyed working with Willie Leacox from the band America, Reg Isadore with Robin Trower, and Pete Thomas with Elvis Costello. Pete’s brilliant as well—and great fun. Advertisement

MD: Are you a fan of Pro Tools?

Geoff: No, I’m not. I just did a session at Capitol studios in California. We recorded the drums analog, and we wanted to do a quick overdub. So we loaded the track into Pro Tools, and it sounded horrendous—like a completely different drumkit.

There’s something weird with the top end in digital recording. Granted, I was born in an analog world. The young kids now have nothing to compare digital sound to. But as soon as you A/B it with analog, you can hear the difference.

Also, some engineers will take a rhythm track in Pro Tools and move this drum or that drum. Maybe the bass drum is not quite lining up. But all they’re doing is taking the human feel out of the record. Fortunately for me, at Capitol we still have analog equipment and guys who know how to use it. It’s just a beautiful sound. Advertisement

MD: Any advice for drummers trying to get a good sound on a budget in a home studio?

Geoff: Don’t get too clever with tons of mics, because you get phasing problems. If you put the snare mic out of phase with the overheads, nine out of ten times the bottom end comes back up and the snare sounds a lot fuller.

I did a Mahavishnu record with Narada Michael Walden on drums. We started with the rhythm section and the orchestra in a big studio. After twenty minutes of recording, we realized we needed to isolate the rhythm section. So we took them into one of the very small control rooms. The drums had one overhead, one bass drum mic, and a mic on the hi-hat-and it turned out to be a great-sounding record. That’s another good example of how much of the sound is the person playing. It was the same kind of thing when we recorded Paul McCartney’s Band On The Run in Africa. Sometimes it’s a plus to be away from the studio and that studio sound. Sometimes those little rooms can give a recording a special character.

MD: Speaking of Band On The Run, how’s Paul McCartney as a drummer?

Geoff: I always loved Paul’s drumming. He has a great sense of timing. When The Beatles were working on drum parts, it was always Paul working it out with Ringo.

MD: How did it feel to work with The Beatles again on the Anthology project, after so many years?

Geoff: Every Beatles fan knows every nuance of every one of those tracks, so I was a little uncomfortable for the first few weeks. Recording ”Free As A Bird” and “Real Love” was a good experience, though. The weird thing was, when we all gathered at Paul’s studio to do that, it was as though we’d only walked off the Abbey Road session four weeks earlier. Paul suggested that we think of it as though John bad just gone off on holiday and left his vocal on a cassette for us, so that’s how we dealt with his absence. Advertisement

MD: Some people might say you were a bit hard on Ringo in your book.

Geoff: Well, it isn’t a question of being hard. It’s what I honestly remember happening on the sessions.

MD: Was he easy to work with?

Geoff: Yes. But there was never a lot of personal conversation. The Beatles were in the studio, and that was their domain. We were up the stairs in the control room. We couldn’t get that close; it was like a ”them and us” situation.

For more on the amazing career of Geoff Emerick, check out his book, Here, There And Everywhere: My Life Recording The Music Of The Beatles (Gotham Books, co-written with Howard Massey).

Editor’s Note: “On behalf of myself and Modern Drummer, we send our condolences to Geoff Emerick’s family, friends, and fans. It was an honor to speak with Geoff on occasion about his illustrious career as one of the Beatles’ main engineers. Still active to his final breath, Geoff was a pioneer in recording drums. I met and spoke to him for the first time for this interview when his book came out, and we remained friends. He will be missed, but his sounds and ground-breaking techniques will live forever.”