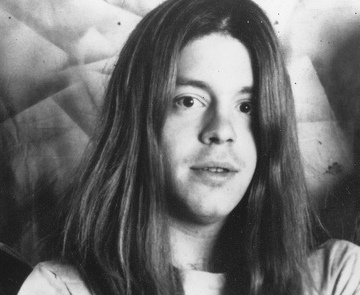

Hüsker Dü’s Grant Hart

The solo artist and former drummer with the highly influential Minneapolis band Hüsker Dü passed away on September 13. The following interview originally ran in the January 2012 issue of Modern Drummer magazine.

In the mid-’80s, Hüsker Dü fused hardcore punk with bittersweet pop, setting the table for an entire generation of alterna-rockers. Two decades on, their drummer—who also happened to contribute half their compositions and vocals—traces the group’s profound path of influence.

by David Jarnstrom

As one third of the legendary Hüsker Dü, Grant Hart redefined what it meant to be a drummer in a punk rock band. Not only did his playing push the stagnant boundaries of the genre, but he also co-fronted the group, writing and singing nearly as many songs as singer/guitarist Bob Mould. The trio’s sound combined the energy and urgency of hardcore punk with the melody and introspection of ’60s pop bands like the Byrds and the Beatles, delighting legions of music fans who were fed up with MTV and mainstream rock radio. Advertisement

While Hüsker Dü was extremely prolific in their output of quality material, the band broke up in 1988, well before the crest of the alternative rock era. Still, they had a massive influence on multi-platinum bands like Nirvana, Green Day, and the Foo Fighters. Even some of the biggest metal bands—including Metallica and Anthrax—are Hüsker fans. Anthrax drummer Charlie Benante even plays in an all-Hüsker Dü cover band called the Dü Hüskers.

Hart has since gone on to have a successful career as singer/guitar player, but he still has a soft spot for drumming. He tracks all the drums and percussion on his records, and he maintains a massive collection of Slingerland Radio Kings. Grant recently sat down with Modern Drummer to discuss his past, and how those he has inspired have been able to return the favor in the present.

MD: When did you start on the drums? What was your first kit?

Grant: I started out with a set of WFL juniors. It was the Ringo kit—the black oyster pearl. I inherited it from my brother. He was a drummer, and he died in an accident at work when I was ten. He had given me some basic [snare] lessons. I think we were into the second book of the Haskell Harr Drum Method. Advertisement

I had once-a-week piano lessons, but the teacher caught me playing by ear and thought that I needed some time away to mature. [laughs] I can read rhythm charts, but I don’t pay attention to the notes that much. I’ve used the excuse for years that sheet music is essentially software for a machine, and I don’t want to be a machine. I played in the school band—drumming, mallets—nothing terribly difficult. It was mostly still by ear. Even in high school they had recordings of what [the music] was supposed to sound like.

Once my brother died, drumming became one activity that I could do no wrong by pursuing it. It made things so easy with my parents. I could sneak out of the house with a pair of drumsticks no problem. If they thought that I was playing the drums somewhere, they would tolerate it very much because it was something that I’d picked up from my brother.

MD: Did you teach yourself how to play the actual drumset then?

Grant: Yeah, pretty much. I would put headphones on and play to 45s. In those days it was pretty easy to tell what people were doing. The song on the record was actually played, so you didn’t have a lot of three-handed drum parts. One thing that I probably spent a hundred hours playing along to was the Fifth Dimension’s “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In.” It was real pop-funky—Boom, bada bop do do bop bop. It had a lot of back-filling going on. Advertisement

MD: That’s something that became part of your style in Hüsker Dü.

Grant: Yeah, keep the snare busy—it kind of came from that. Also, the most important song for a drummer my age to know was the Surfaris’ “Wipeout,” because if you were a drummer in 1973, all of the high school kids would be like, “I bet you can’t play ‘Wipeout.’” [laughs] The surf stuff was real attractive to me because a lot of it was Hal Blaine, and he’s doing some really nice, tight stuff—really straight rolls for fills. I integrated that with the forever-accenting snare stuff I picked up from “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In.”

MD: What were your first live experiences like? How did you learn to play in bands?

Grant: A big advantage for me was doing as many substitution gigs as I did—there’d be a lot of polka, but there’d also be the Greek New Year’s Eve party and the Hawaiian stuff. I had gigs where I got the job because I had a Hawaiian shirt. [laughs] Some of these polka guys—if you didn’t have, like, a clock going inside your head, they were surly. If you don’t have good time, how are you going to know it? It’s only by playing along with something that you can regard as being strict.

MD: How old were you when Hüsker Dü began?

Grant: I was seventeen when Hüsker Dü played the first time. I had been playing the drumset for a good six years.

MD: Were you still in high school?

Grant: Yeah. Bob Mould was in his first year in college. [Bassist] Greg Norton did not matriculate. I went to the Minneapolis College of Art and Design for a year for visual art.

MD: You made quite a leap, going from polka to punk. In the early days Hüsker Dü was playing a million miles an hour!

Grant: Part of it’s myth, part of it’s more of a development than a sudden change. For example, our first album, Land Speed Record—we’d had plenty of mid-tempo to slower stuff, but we concentrated all our fastest material into one set to deliberately make that record. We continued to play the fast set on tour after the first LP; it’s what people expected. There was more emphasis on speed than melody, clarity of performance, accuracy of trajectory…it was all about velocity. And it got to the point where we could play it in half of the time that it was originally recorded. Advertisement

It’s arguable that there was a deliberate concentration of the very fastest stuff played faster to conform to this new thing that was starting to happen in different places. In the big picture certainly we were way ahead of the time, but there was the Dead Kennedys, Black Flag, DOA in Vancouver…. A few years later there were so many bands like that, we changed the trajectory again and deliberately started playing more pop stuff because that was a surefire way to piss off the youngest of the hardcore bands. [laughs]

MD: Did you enjoy playing that fast?

Grant: The exhilaration of just slamming a roomful of people up against the wall—there’s nothing quite like it. There were other things that were more rewarding after we found out there were plenty of other people who played that way.

MD: Hüsker Dü never wanted to be part of a particular scene.

Grant: All of our hair got unsuitably long for the audience’s comfort level. [laughs] We enjoyed throwing something challenging at them. Are people coming to hear the band or just fit in with something? We sent the message: “Don’t worry about fitting in. Do what’s right and fit into that. To thine own self be true.” Advertisement

We were very fortunate in the way that we converted ourselves because what was going on became so overloaded with politics that the singers, the composers, didn’t know anything about. It’s also arguable whether the lyrical content even matters when things are going at that volume. We could have been singing about anything.

There’s something attractive about negative attention—that whole rock ’n’ roll badass thing. It’s badass to be able to do something very intensely, but it’s also badass to not need to do it for your own self.

MD: How would you gear up for the intensity of a Hüsker Dü show?

Grant: I wasn’t that keen on stimulants after Land Speed Record. The old-time truck drivers had a formula that incorporated coffee, whiskey—just enough to kill fatigue pain—and keeping the cab of the truck as hot as you can get it so you’re metabolizing everything as much as possible. That could be applicable to what we were doing. I wouldn’t load myself up on a lot of beer. I would drink water and as I was ready to get up and play I would drink a double shot of bourbon and that would take care of the anesthetic of the equation. Advertisement

MD: You had better technique than many punk drummers back then—powerful, yet economic. How did that develop?

Grant: Technique is what people arrive at that produces the best result. If the result that we were looking for is playing longer, faster, and not being quiet, you’re going to take into account everything that contributes to that.

Most of [my technique] is from discovering the path of least resistance. It was about keeping things loose. It’s a different kind of strength, the kind of drumming that I was doing. You’re letting the snap do the work. You’re letting the bounce do as much of the work as possible. Snap it down and then relax and catch it when it’s up, and snap it back down again. Releasing the grip right after the stroke so that you can just keep your hand around the stick, but not having to lift it.

A lot of people do too much—I had an instructor that called it “pump handling,” where, you know, they keep everything too stiff. I would sit pretty high and let the drumhead be the elevator. If it’s going to bounce anyway, why lift it? Advertisement

MD: Did sitting high help facilitate your singing as well?

Grant: Couldn’t have hurt. But also the energy for the kick drum was being directed straight down to the pedal instead of forward. The more upright you sat, the less you kicked the drum forward. When you’ve got mayhem happening on stage, you don’t want it happening on top of your drums.

MD: It’s amazing that you were able to play the style of music you played, and at the same time sing so clearly—especially on the songs where you’d sing lead. How did you do it?

Grant: It’s concentration. I thought about the drums as little as possible while singing. It evolves more into a dance than a musical performance. You know where everything needs to be at a given time, and then deliver it as best you can.

MD: Your setup seemed pretty ergonomic.

Grant: Early on I abandoned the second tom-tom. Eventually I lowered the ride cymbal.

MD: And boy, did you ever love that ride cymbal. [laughs]

Grant: My hi-hat was mostly just a place to put my left tennis shoe.

MD: Wait, I thought you played barefoot?

Grant: Only for about the first four or five years in Hüsker. I got out of that by the time we did Flip Your Wig. I got tired of picking glass out of my feet.

MD: What was the rationale behind barefoot drumming in the first place?

Grant: You’re not picking up as much weight—you’ve got less to kick forward. Everything you throw down you have to pick up.

MD: What size stick did you prefer?

Grant: I was using 7As and I was playing them backwards. But I would still get the nylon tip for the times I’d want to switch them around and get the really nice contact with the nylon on the ride. I guess I always wanted to maximize that bright hit. Advertisement

MD: Speaking of bright, your records have a unique sound to them. The drums have a light, almost ping-pong ball sound to them.

Grant: To tell you the truth, a lot of the Hüsker stuff was poorly produced. Not to slag off the band, but I really think that had we known the longevity of some of those records, we would’ve—out of respect for that—maybe occasionally have done a second or third take on some songs. We rehearsed the hell out of things, but some of the tones…. [grimaces]

MD: Did you ever use a click track in the studio?

Grant: There’s no click. There’s a massive tempo shift at the beginning of “Diane” on Metal Circus, but usually it’s very consistent.

The biggest compromise made by me was to record the last three albums without cymbals—we’d add cymbals after. It gave me the opportunity to use room mics without having a battle going on between the cymbals and the guitar tones—just to make it so that you can EQ the snare without screwing up the sound of the cymbals. You can facilitate better sound.

Replacing the cymbals is easy—removing them is more difficult. I would just put a huge piece of carpet over the cymbal—it was kind of a compromise because Greg needed the cymbal to play in time, so what I did was, I had a drum pad with a cymbal chip in it. I played that so I could monitor it and remove it to add the real-sounding stuff. Advertisement

MD: What was your approach to tuning?

Grant: I’d have a small concentric hole in the bass drum and some stuff padded right up against the head. But I tried to keep everything else as free-ringing as possible.

MD: You’re known for your love of Slingerlands.

Grant: The first set of Radio Kings that I ever found, it was like, hearing those tom-toms… The toms weren’t even their most salient point. The most desirable thing about the Radio Kings was the bent-wood snare. But the first time I heard the 13 and the 16, it was like, “God, this is how drums should always sound.”

On tour, I would call drum shops and pawn shops at 8 in the morning and buy them up. I kick myself in the ass because I don’t know why I was not attracted to Slingerlands before. I probably got into them right before New Day Rising.

MD: As Hüsker Dü evolved, you got to stretch out a lot more with your drumming, especially on the songs you were writing. Was some of this to satisfy your urges as a drummer and not play the same beats over and over? Advertisement

Grant: I can’t say that it was in a response to anything seeming “samey,” although we got out of the hardcore thing at a good time. It had become so formulaic. I remember making a conscious effort—realizing that someone could ask us to do “Stars and Stripes Forever” and it would end up sounding like Hüsker Dü—I would try to bring things as uncommon to our practices as possible.

MD: Your song “Tell You Why Tomorrow” on Hüsker’s final record, Warehouse: Songs and Stories, even features a mini drum solo of sorts.

Grant: The drum solo had become such a negative cliché. That was one of the things that punk was supposed to get rid of. [laughs] But that was intended as a break fill, to propel it into the next verse.

It was always a little bit of a point of tension; I wouldn’t solo myself—any time my songs had an open eight, this is where the guitar solo would be. I’m glad for everything that I didn’t have to try and talk [Bob Mould] into. Advertisement

MD: You made it on the singles chart this April when Green Day released a cover of your song “Don’t Want To Know If You Are Lonely” from Candy Apple Grey. It is extremely cool that they included your original version—on the A side, no less.

Grant: That was very flattering. I’ve been told it was the most successful Record Store Day release. I don’t know if that’s true or not. That all ends up trickling down. Every concert I play, the youngest person there has heard my stuff because of somebody else—or else they’re awful damn curious.

MD: Hüsker Dü never really got the big payday the bands that followed in your footsteps enjoyed. Does that ever eat at you?

Grant: There’s a certain amount of satisfaction that comes from innovation. How flattering is it for me to say: “So and so took everything of mine and made millions?” Well, yeah, that has happened, but it has nothing to do with what I set out to do when I did it. It’s not like those people made what I was doing any more difficult. Advertisement

I end up having to spend a lot less money on bodyguards than the people who are super successful. If I met the right bodyguard that I wanted to give the money to, then maybe I’d work on being a more valuable body to guard. [laughs]