Ringo Starr Meets the Beatles

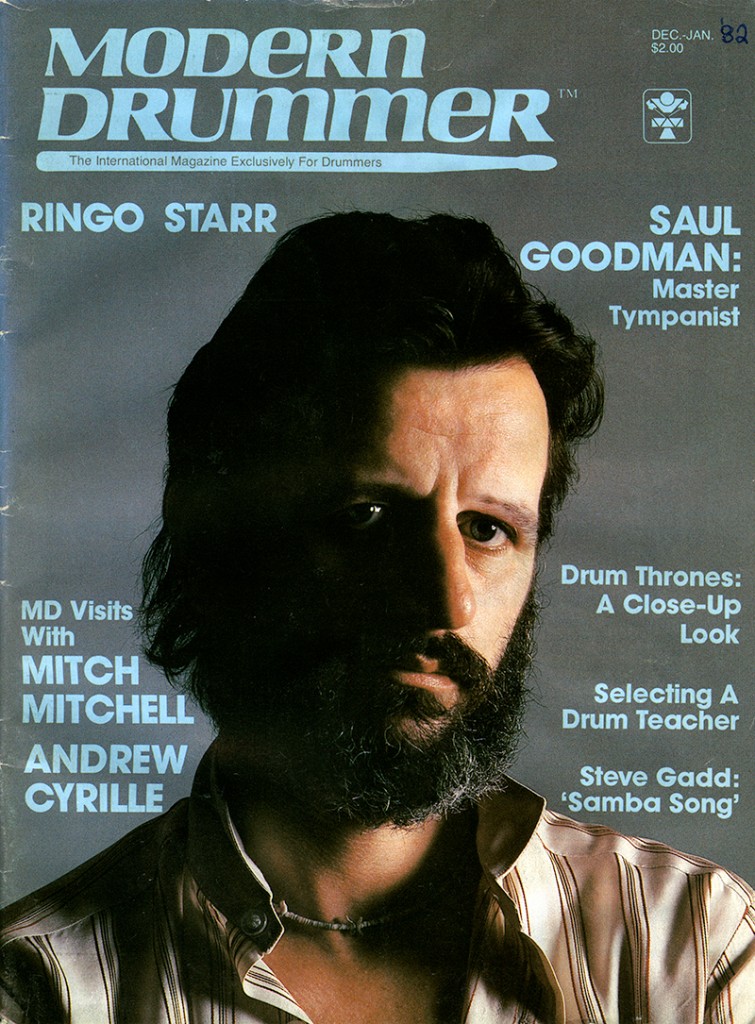

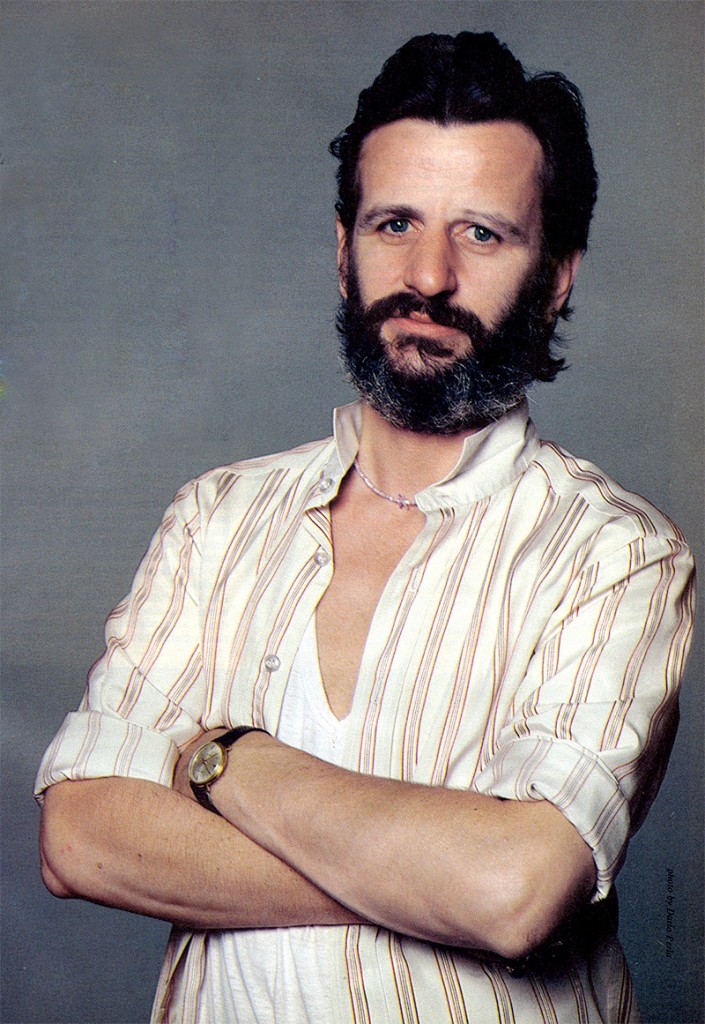

We travel back to the December 1981/January 1982 issue of Modern Drummer, which featured a cover story with former Beatle Ringo Starr. In the piece, Ringo talked extensively about growing up in England, sharing the most remarkable ride in pop history with John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison, and embarking on his solo career following the group’s 1970 breakup. Here, in celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Beatles’ February 1964 arrival in America, we focus on Ringo’s recollections of his early years with the Beatles.

We travel back to the December 1981/January 1982 issue of Modern Drummer, which featured a cover story with former Beatle Ringo Starr. In the piece, Ringo talked extensively about growing up in England, sharing the most remarkable ride in pop history with John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison, and embarking on his solo career following the group’s 1970 breakup. Here, in celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Beatles’ February 1964 arrival in America, we focus on Ringo’s recollections of his early years with the Beatles.

Ringo: I was playing with Rory Storm and the Hurricanes about eighteen months, two years [before I joined the Beatles]. We’d all played the same venues and, at the time, Rory and the Hurricanes used to be top of the bill. There’d be all these other bands on, and occasionally the Beatles would play. It ended up that they were the only band I ever watched, because they were really good, even in those days. One morning, I was in bed, as usual. I don’t like getting up in the day because I live at night. So a knock came at the door, and [Beatles manager] Brian Epstein said, “Would you play a lunchtime session at the Cavern with the Beatles”? And I said, “Okay, okay, I’ll get out of bed,” and I went down and played. I thought the band was good, and it was great for me to play.

MD: Were they different from other bands playing at the time?

Ringo: Yeah, they were playing better stuff. They were doing very few of their own songs then, but they were doing really great old tracks—Shirelles tracks and Chuck Berry tracks, but they did it so well. They had a good style. I don’t know, there was a whole feel about Paul, George, and John. And Pete [Best], it’s no offense, but I never felt he was a great drummer. He had sort of one style, which was very good for them in those years, I suppose, but I think they felt that they wanted to move out of it more. So I just played the session, and then we went and got drunk, and then I went home. Advertisement

MD: So it was a one-shot deal.

Ringo: It was a one-shot, but we knew each other. We met in Germany when Rory played there and so did the Beatles, but we didn’t play with each other. There was heavy competition because we used to play weekends, twelve hours a night between the two bands, and we’d try to get the audience in the club, so there was a lot of competition. And then, at the four- or five-in-the-morning set, if the Beatles were left on, I’d usually still hang around because I was drunk, asking them to play some sort of soft sentimental songs, which they did. So basically, they were at one club and we were at another club, and we ended up at the same club. That’s how we sort of said hello. We never played with each other, but then out of the blue, Brian came and asked me to play.

MD: Was that an audition for you from their standpoint?

Ringo: No, Pete wasn’t well or something, so they needed a drummer for the session and asked me, or asked Brian to ask me. So I went and played and that was all there was to it. This went on for about six months, where every couple of weeks I’d play, for whatever reasons. Then there was talk about me joining and I was asked if I would like to. I said, “Yeah,” and then went away with Rory to play this holiday camp again, because it was good money for three months and we just played what we wanted. About five weeks into this three-month gig, Brian called and asked if I would join the Beatles. I said, “Yeah, I’d love to. When”? He called me on a Wednesday, and he said, “Tonight.” I said, “No, I can’t leave the band without a drummer. They’d lose a six-week gig, which [is how long] they have left to go.” So I said I’d join Saturday, which gave Rory the rest of the week to find a drummer.

MD: Why did you choose to join the Beatles if both bands, in essence, were starving?

Ringo: Well, I’d rather starve with a better band, and I felt the Beatles were a better band. And by then we weren’t actually starving. We were making…not great money, but enough to live on. And the Beatles were making a bit more—they were coming up real fast. But I loved the band so much. And I thought I had done everything our band could do at the time. We were just repeating ourselves. So it was time to move on. And I liked the boys as well as the music. Advertisement

So I left on Saturday, played on Saturday night, and it was in every newspaper. There were riots. It was okay when I just joined in and played a gig and left, but suddenly I was the drummer. Pete had a big following, but I had been known for years in Liverpool, so I had quite a following too. So there was this whole shouting match, “Ringo never, Pete forever,” and “Pete never, Ringo forever.” There was this whole battle going on, and I’m just trying to drum away. But they got over it and then we went down to make a record.

I’m not sure about this, but [I think] one of the reasons they also asked Pete to leave was George Martin, the producer, didn’t like Pete’s drumming. So then when I went down to play, he didn’t like me either, so he called a drummer named Andy White, a professional session man, to play the session. But George has repented since. [laughs] He did come out one day, saying it—only when he said it, it was ten years later. In the end, I didn’t play that session. I played every session since, but the first session, he brought in a studio drummer.

MD: There are reportedly two versions of the first release, “Love Me Do,” one where Andy White plays and one where you play.

Ringo: I’m on the album and he’s on the single. You can’t spot the difference, though, because all I did was what he did, because that’s what they wanted for the song.

MD: It’s also been said that Martin handed you a tambourine.

Ringo: Yeah, and told me to get lost. I was really brought down. I mean, the idea of making a record was real heavy. You just wanted a piece of plastic. That was the most exciting period—the first couple of records. Every time it moved into the 50s on the charts, we’d go out and have dinner and celebrate. Then when it was in the 40s, we’d celebrate. And we knew every time it was coming on the radio and we’d all be waiting for it, in cars or in someone’s house. We wouldn’t move for that three minutes.

Advertisement

Ringo: Yeah, and told me to get lost. I was really brought down. I mean, the idea of making a record was real heavy. You just wanted a piece of plastic. That was the most exciting period—the first couple of records. Every time it moved into the 50s on the charts, we’d go out and have dinner and celebrate. Then when it was in the 40s, we’d celebrate. And we knew every time it was coming on the radio and we’d all be waiting for it, in cars or in someone’s house. We wouldn’t move for that three minutes.

Advertisement

And then, of course, the first gold disc and the first number one! But like everything else, when you’ve had five number ones, one after the other, and as many gold discs as you can eat, it’s not boring, but it’s just that the first couple of records were so exciting. I think they are for everybody. It’s like sweets every day, though. You get used to it. So I was really brought down when he had this other drummer, but the record came out and made it quite well, and from then on I was on all the other records, with my silly style and silly fills. They used to call it “silly fills.”

MD: Who?

Ringo: Everyone used to sort of say, “Those silly fills he does.”

MD: And yet, your playing turned drumming around for a lot of people.

Ringo: But we didn’t know that then. Everyone put me down—said that I couldn’t play. They didn’t realize that was my style and I wasn’t playing like anyone else—that I couldn’t play like anyone else.

MD: You really had an affinity for the toms.

Ringo: That was my style. Also, I can’t do a roll to this day, and I hit with the left first, while most drummers do it with the right first. Mine might be strange in its way, but it was my style. I can’t go around the kit, either. I can’t go snare drum, top tom, middle tom, floor tom. I can go the other way. So all these things made up these so-called “funny fills,” but it was the only way I could play. And then later on, after I was always put down as a drummer, I came to America and met Jim Keltner and people like that who were telling me they were sick of going in the studio, because they’d only been asked to play like me. So it was very good for my ego, and it turned out that I wasn’t silly after all. Advertisement

MD: George Harrison said that he felt the response to the Beatles was some sort of hysterical outlet for people. The four of you must have sat around and conjectured as to what was going on. It had to be mind blowing.

Ringo: Well, we enjoyed them getting their hysterical needs out, because no one came to listen to our gigs. They bought records to listen to. They just came to scream and shout, which was fine, but after four years I was becoming such a bad player because I couldn’t hear anything. Because of the noise going on, all I had to do was just constantly keep the time, so we’d have something to follow. If you look at films, you’ll see I’m looking at their mouths—I’m lip reading where we’re up to in the song because I couldn’t hear the amps or anything.

We were becoming bad musicians, so we had the discussion about it. Besides, we could play in any town or country in the world and get the same response, but only the four of us would know if we played any good, and that was very seldom, because we couldn’t hear. So you’re getting the same response for a bad gig, and it wasn’t any help. You only wanted applause if you did something that worked. It was pointless playing on stage anymore, so we decided to go into the studio, where we could get back to playing with each other again. [That] got us playing again and exploring a lot of avenues of the technology of the studio, which, compared to now, was Mickey Mouse. Advertisement

MD: What were the highlights of your time in the Beatles, in terms of the band and your playing?

Ringo: As an act, which we were, the Palladium or the Ed Sullivan Show, because they were definite moves in a career. We still wanted to be the biggest band in the world. Not that we knew it would be a monster, but we knew we were aiming somewhere and the only [way to measure] it is popularity. And we did become the most popular group on earth, so there’s all those moves.

[In terms of playing], the “Rain” session, where something just comes out of the bag, that just arrives—that’s exciting. It’s not a conscious thing—it just happens, and some sessions can get exciting. Musically, sometimes you would be blown away with what came out, but not every time. Other times you did the best you could, and if it worked, great. But sometimes magic just came out of the blue, and it comes out for everybody.

To play with three other people, any other people, when it works is when everyone is hitting it together, no one is racing, no one’s dragging, the song is good or the track is good and the music is good…. If you’re not a musician, I don’t know if you’ll understand it, when three, four, or ten of you, or a hundred-piece orchestra, hit it together for as much time as you can—because there’s very few times it goes through the whole track, never mind the whole album—there’s a magic in that that is unexplainable. I can’t explain what I get from that. It’s getting high for me. Just a pure musical high. Advertisement

MD: How does someone maintain his perspective on being a human being when the world has made him larger than life?

Ringo: I think you’re born with it. Also, at certain periods I did go over the edge and believe the myth, but I had three great friends who told me, “You’re bullshitting yourself.”

MD: But weren’t they going over the edge as well?

Ringo: Yes, but they had three friends too, to tell them they’re bullshitting themselves. It’s not that we actually all did it at once.

MD: What kind of effect would you say the Beatles, the fame, etc., has had on you today?

Ringo: I don’t know. It’s hard to say where I’d be if it hadn’t happened. But it did, so I’m exactly where I feel I should be. Does anybody know what he would have done if he hadn’t been doing what he did at the time he was doing something? It’s impossible to tell. The difference would be that you wouldn’t be interested in talking to me if I had just been playing some little club somewhere. But whether I would have been a different human being…it’s hard to tell. I’m sure I must have changed, but would I have changed had I gone through a whole different type of life? I don’t know. The effect it all had, from being born to today and everything that went on in between, is that we’re sitting here in the garden, trying to say hello.

Original interview by Robyn Flans.