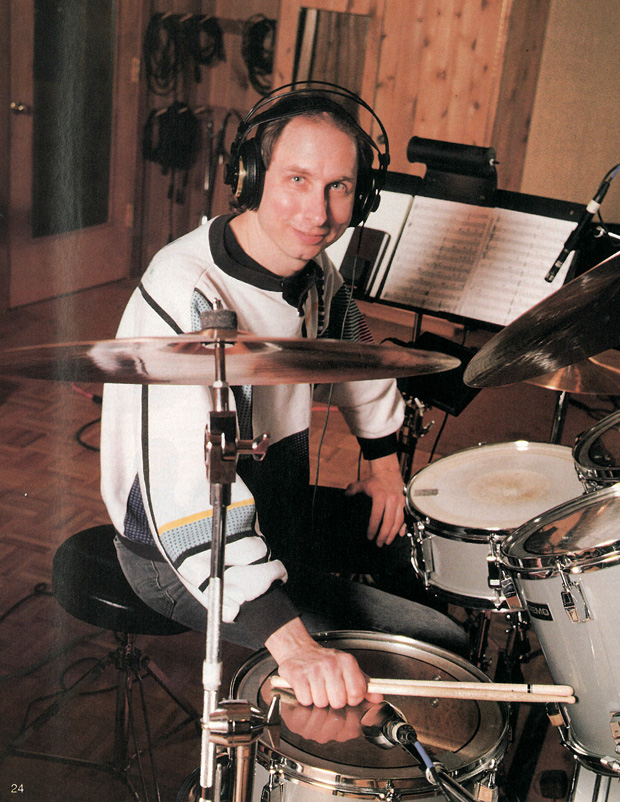

Nashville Studio Great Tommy Wells Passes

We were saddened to hear of the passing of Nashville studio great Tommy Wells this week. In honor of Tommy, we’re presenting a portion of his first Modern Drummer feature, from August 1990.

“As a session player you take total satisfaction from good playbacks and sleeping in your own bed every night.”

Tommy: The best part of session drumming is that every week is different. One week I start off playing country radio stuff, then pop music, then perhaps a jazz gig. The next week I may be doing a gospel album, a hardcore country date, and then a television show, and at the end of that week I might gig with the rhythm and blues band the Prisoners of Love. It can always change, but that is how diverse my schedule can be and usually is.

MD: Was there any specific training you had to prepare you for the variety of styles you play?

Tommy: Not really. I just started doing gigs when I was very young. My dad played organ for the fun of it when I was growing up in Detroit, and he had friends who were players. They did everything from the wedding scene to playing bars, and they’d come over on Sundays to play and just hang out, which first exposed me to playing drumset. I was also in the band at school at the time.

Later, when I was in high school, we lived in Marion, Indiana, and I played standards gigs with the local guys. I also played in a rock ’n’ roll band. With the rock band we did a lot of local gigs in front of bands like the Outsiders, the Left Banke, and other pretty popular groups. We’d only make about fifteen or twenty dollars apiece. While that was all going on, the older guys playing the standards gigs called me, and I came to realize that I could make fifty or sixty dollars on the weekends and still have time to play rock ’n’ roll with the younger cats. Advertisement

MD: In the early ’80s you had some success with a group called RPM, which was a favorite band of musicians everywhere.

Tommy: That group wasn’t real successful, in my opinion, but we enjoyed some success among musicians. RPM started out as a studio project here in Nashville. The guitar player, Mark Gendel, was from Toronto. He came to Nashville to write, and met Robert White Johnson. The bass player, Jimmie Lee Sloas, had worked with Robert before, and I was asked to do the demos. It went so well that they asked me to get involved, and it turned into a band. We didn’t play live very much—maybe thirty gigs over the four and a half years that I was involved. It was mainly a studio thing. But we did do a video and played on Solid Gold once.

MD: What led you to play like you did on those RPM albums? You had such a fresh drum sound and approach on those records.

Tommy: I was a writer on that material, but what I wrote was the drum parts, which turned out to be a large part of those songs. I would take my parts to rehearsal and put them on tape and then build the rest of the song from the ground up. “Ceylon Ceylon,” “Pay Attention,” and “It’s Only Water” were written completely around the drums, and I had to increase the size of my set to play those tunes with all toms. I had been listening to a lot of African music and also to how Phil Collins had made drum patterns a very important part of his songs. One of the records I had listened to a lot and that influenced me was the Daktari soundtrack that Shelly Manne had done with African percussionists. I really loved that stuff and made it work on the drumset. I came up with all kinds of stickings and feels and applied them, and then I took them to the rest of the band. Usually I would play ride time on the choruses and use the verses for the more exotic drum patterns.

Our rehearsals with RPM were preproduction rehearsals, and we had everything miked up and ready to record when we went in. I’d put down my parts at one rehearsal and then the other guys would work their patterns in. We really wanted to work with producer Gary Langan, who had done some things that we had heard, like the Yes song “Owner Of a Lonely Heart.” We wanted that same big, ambient drum sound, so we went to Sarm Studios in London to get that big drum sound on those tunes. Advertisement

MD: Your early experiences with studio work were obviously positive for you, because you’ve become known for session work and being a “specialist.” Now that you’ve done it for quite some time, does it still hold a fascination for you, or is it more like just going to the office and doing your job? To many, it seems like a glamorous career.

Tommy: Sometimes it is like going to the office. So much depends on the situation on any given day. Some of the time we get to play really great music, and some of the time it’s not so great. That’s when it can really seem like a job. When that happens—for whatever reason—it comes down to pulling it out of the fire. You hope for the best, but being a professional means that you do your best no matter what the situation, good or bad.

MD: You’ve played on so many hit records, it seems as if you must have a special “touch.” Since you have really completed your job when the drum tracks are done, and you aren’t a member of the band, how does it feel to do the job and not get the credit? Advertisement

Tommy: Most of the time you just cut a record, and when it makes it to the Top-10, you really feel good about it. When you do something fun and it does well, it’s a good feeling, too. But I’ve got to admit that when a record is doing well and you’re not getting the recognition, it’s natural to be a little disappointed. You wish that someone would say something and give you some credit, besides the local press.

MD: What do you think studio players can do about changing their status of anonymity?

Tommy: You never hear about the guys who are working every day. Session players rarely become well known to the listening public. Larrie Londin is an exception to that, and is an excellent example, because he’s a great drummer, a great personality, and an excellent promotion man, which I mean in the very best sense. He is the one guy from Nashville who has really become well known in music merchandise circles, because of the clinics and other things he does. Other session players can learn from him, but it takes that special personality to do what Larrie does. The guys playing on records every day are different from rockers, in the respect that they don’t promote like rockers do and constantly need to. That is so far removed from what I do; it’s just a totally different game. You take total satisfaction from good playbacks and sleeping in your own bed every night.

MD: From where you sit, what do you see as being necessary to survive the politics of the music business? How can session players become more aware of that situation to get the gigs, keep getting the gigs, and become known? Advertisement

Tommy: Well, I don’t do any schmoozing, if that’s what you mean. But some of the guys in town carry tapes around and really work at marketing themselves. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. For the guys who come in from L.A. with their résumés and who are heavy hitters, it seems to work. I don’t think that it works as well for other guys, because they don’t have those records and credentials to show. I think in general the people who are hiring don’t like to listen to audition tapes. Some work might come out of one, but the guys I see say, “I’ve carried tapes around, but I just haven’t gotten anything.” The way it was for me is that I came to town and played with Gene Cotton at the end of 1976, and then I got to play on his records because his producer liked the way I played. Gene was also involved with some other artists as a producer and a writer, so I played on some of those sessions, and it started to snowball for me.

MB: If you were asked to give advice to up-and-coming players, what would you tell them?

Tommy: I think setting goals gives you something to shoot for and really work toward. I never had the specific goal of being a studio player; I just wanted to be in a successful group. As the years went by and the groups sort of fell apart around me, the studio thing just evolved. When that happened, then it became my goal to do a lot of studio work; but it wasn’t the original goal. Things change, and you’ve got to go with the flow.

Original interview by Michael Briggs. Photo by Rick Malkin.