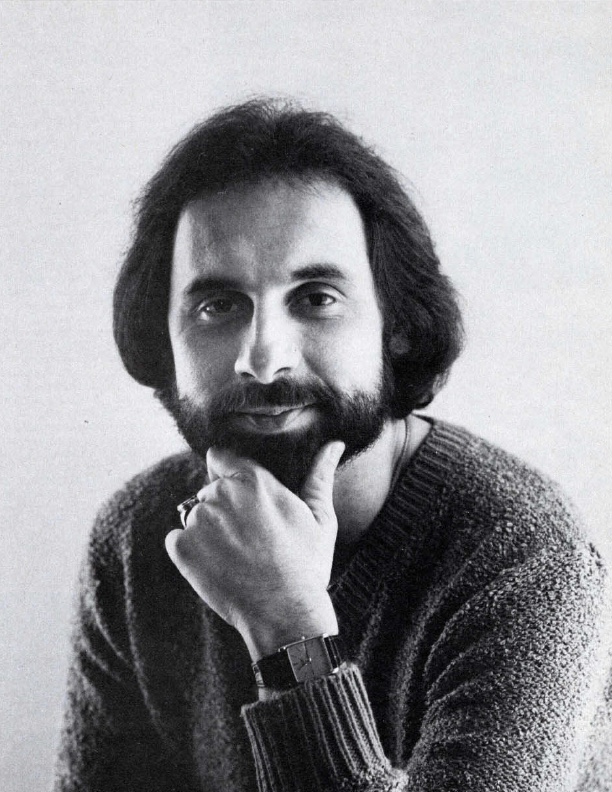

The Artistry of Joe La Barbera

Photo by Tom Marcello

“But Buddy treated me great,” Joe quickly adds. “I saw the other side of the Buddy people talk about when they refer to those tapes where he’s ranting and raving. We were sharing a dressing room, and the guys would file by our room to get to theirs. He’d single a couple of guys out and give them all kinds of hell. But once they’d passed, he’d turn around and give me a wink, like, ‘don’t pay any attention to this. I’m just tightening up the ranks.'”

Although Joe was barely out of his teens at that point, he’d been a professional musician since he was six years old, playing in a family band that included his parents as well as his older brothers Pat and John. Pat went on to play saxophone with such leaders as Rich and Elvin Jones, and John became a noted arranger and composer for such bandleaders as Rich, Woody Herman, Bill Watrous, and others.

Joe went on to work with Gap Mangione, the Woody Herman big band, Chuck Mangione, and John Scofield before joining The Bill Evans Trio, with whom he worked until Evans’ untimely death in 1980. Afterwards, La Barbera worked with singer Tony Bennett for twelve years, and since then has worked and recorded with such artists as Conte Candoli, Bud Shank, Alan Broadbent, Kenny Wheeler, and the WDR Big Band. Since 1994 he has been on the faculty of The California Institute For The Arts (CalArts). Advertisement

La Barbera has also been leading his own group since the early 1990s, and with that band he has recently released his first album as a leader: The Joe La Barbera Quintet Live on the Jazz Compass label (www.jazzcompass.com). Joe’s album is one of four initial releases on the new label, of which Joe is a co-owner. He also plays on new Jazz Compass releases by The Tom Warrington Trio (Corduroy Road) and Clay Jenkins (Azure Eyes).

Joe’s playing is solidly in the mainstream jazz tradition, and he is equally at home within a trio or a big band. His level of interaction with soloists is more that of a partner in the improvisational adventure than of an accompanist, and yet he is totally supportive of the soloist throughout the process. His own solos display plenty of chops as he does variations on classic bebop phrases, but it’s the musicality that lingers in the memory after the specific licks have passed by.

MD: I’ve always been impressed by the way you can project just as much momentum and intensity through the drums when you’re playing softly with an acoustic trio as when you’re digging in with a big band. Advertisement

Joe: It’s something I worked toward. First of all, when I was coming up in the clubs in the ’60s, bass players didn’t have amplifiers, and pianos weren’t miked. So you were playing at a different volume level. You had to make it happen at all the levels. It couldn’t just be intense when it was burning and be lukewarm at all the other dynamic ranges. You had to make it intense all the time. Even on ballads, there’s an insistency, even though it’s not in your face. But it has the energy no matter what.

As far as how I do it, you’ve got to be focused on what you’re trying to achieve. When you concentrate on something, it automatically comes out in your playing, although it may take a little while for you to refine it. Technically, I don’t know what else to tell you, except maybe get a cheap record player and play along with records.

MD: In fact, once when I complimented you on your touch, you explained that when you were a kid, your older brother Pat would pick out records he thought you should play along with. You said you only had a little record player and no headphones, so you had to play soft to hear the record over your drumming. Advertisement

Joe: That’s absolutely true. Some of those really fast tempos, like on Miles In Europe or Four And More, were ridiculous, but I tried to do it. Somehow it worked.

The first jazz record I remember Pat bringing home was The Lester Young Story, and on that album there’s a tune called “Gigantic Blues” that featured Jo Jones. I really tried to play like Jo Jones because Pat was trying to play like Lester Young. But there are a couple of tracks on that album that feature a more bop-oriented rhythm section with Connie Kay on drums, so I was also hearing the transition.

Then Pat got a record called Birdland All-Stars On Tour with Kenny Clarke on drums. We wore that record out. What Klook [Kenny Clarke] did on that album relates to something about Philly Joe Jones on the Bill Evans Everybody Digs album; they played those entire albums with just snare drum, bass drum, hi-hat, and ride cymbal – no tom-toms. But the music they made is amazing.

They had control of the drumset in its most basic form. And you’ve got players today like Leon Parker who have made a jump back to that kind of minimalist approach. I think the idea from the boppers was that if you could make it happen with these few items, then when you added more drums and cymbals, you had more ways to express yourself. But to be able to do it with just a few things was kind of a test. Advertisement

MD: I assume that Art Blakey was one of your influences, judging by one of the tunes you wrote for your new album, “Message From Art (For Art Blakey).”

Joe: One day this tune came to me and I thought it sounded like Blakey. A friend of my brother’s originally turned me on to Art. The first record he played for me was “Caravan.” I couldn’t believe what I was hearing’the amount of energy and sound that Blakey got out of the drumset blew me away. Blakey’s The Big Beat album was on a jukebox, believe it or not, at a pizzeria in our hometown. So we would go in there every night and play it until the owner took it off the jukebox because he got so sick of us playing it.

MD: In the recent Hal Leonard publication Drum Standards, one of the transcriptions you did was Blakey’s solo on “Paper Moon.”

Joe: That solo is constructed beautifully. It’s simple but it builds very effectively, and the way he phrases across the downbeat of the bridge is great. He’s not boxed into four- and eight-bar segments.

MD: When you were coming up, did you memorize solos note for note?

Joe: I learned that Blakey solo because it was just one chorus. But I didn’t generally learn solos note for note; I would just cop particular licks. A lot of it was stuff that everybody was doing. There’s a standard repertoire of bebop language that all the drummers played’max, Philly, Roy Haynes – but they all sounded completely different doing it. So I learned from all of those guys. Advertisement