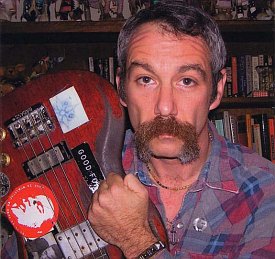

Mike Watt: Pouncing on Opportunities

by Adam Budofsky

Mike Watt is a flesh-and-blood superhero to anyone who’s followed the do-it-yourself alternative music scene over the past twenty-five years. As the spieling rhythmic force behind the legendary San Pedro, California, band the Minutemen, Watt, along with late guitarist/singer D. Boon and drummer George Hurley, proved how inclusive punk rock could be as a style—and as a lifestyle.

Mike Watt is a flesh-and-blood superhero to anyone who’s followed the do-it-yourself alternative music scene over the past twenty-five years. As the spieling rhythmic force behind the legendary San Pedro, California, band the Minutemen, Watt, along with late guitarist/singer D. Boon and drummer George Hurley, proved how inclusive punk rock could be as a style—and as a lifestyle.

Incorporating elements of jazz, funk, avant-garde, and even—gasp!—classic rock, the Minutemen produced a treasure trove of recordings that walked boldly through the doors kicked down by the punk revolution. Shocking in their passion, invention, and scope, and impossible to overestimate in terms of influence, the Minutemen’s songs are revered by anyone who came of age in the musically turbulent ’80s.

Following the death of D. Boon in 1985, Watt and Hurley were persuaded back in to playing by guitarist and Minutemen fan Ed Crawford. The new band, fIREHOSE, put out several well-received albums that continued the Minutemen’s adventurous ways. Watt went on to work with Sonic Youth, J. Mascis, Porno for Pyros, and Iggy & the Stooges, among many others, in addition to putting out his own albums, including the popular alternative all-star double disc Ball-Hog or Tugboat? Advertisement

Recently Watt rejoined Hurley in the poetic groove-punk collective Unknown Instructors. He’s also continued working with Stephen Perkins’ Banyan, whose recent release, Live at Perkins’ Palace, showcases both musicians’ deep, worldly rhythmic communications.

MD engaged in some communication of our own with the estimable four-stringer, initially for the purpose of getting a quote for the introductory pages of The Drummer, MD’s recently released coffee-table book. We only needed a sentence or two, but Mike was so thoughtful and generous with his time, we kept the tape rolling, figuring we’d decide what to do with all this good stuff later. Well, “later” is now….

MD: The first Unknown Instructors album was largely improvised, right?

Mike: It’s totally improvised. A poet from Toledo, Ohio, named Dan Maguire put the project together. He used to come to fIREHOSE gigs, that’s how he met me and Georgie. Guitarist Joe Baiza of Saccharine Trust goes way back with us. But Dan thought up this idea: “Hey, why don’t you guys just jam and I’ll do poems over it”? Advertisement

MD: How do you find that sort of situation—exciting, nerve-racking, both…?

Mike: It’s much different from the other thing, where you organize pieces and practice them. But, you know, to keep learning you’ve got to keep putting yourself in challenging situations. You stop learning, you stop living.

MD: What kind of things did you find that you had to focus on in an improvising situation?

Mike: Well, any time with jamming…I also have this thing with Stephen Perkins called Banyan where we’re making stuff up at the moment…but what I’ve learned is you’ve got to listen, because you don’t know where it’s going—unless you want to strong-arm it. But to me, any time you’ve got an ensemble, the key is to make it an interesting conversation. But jamming versus working with songs—they’re just different perspectives on the same thing. We’re trying to make these machines laugh and cry.

Mike: Well, any time with jamming…I also have this thing with Stephen Perkins called Banyan where we’re making stuff up at the moment…but what I’ve learned is you’ve got to listen, because you don’t know where it’s going—unless you want to strong-arm it. But to me, any time you’ve got an ensemble, the key is to make it an interesting conversation. But jamming versus working with songs—they’re just different perspectives on the same thing. We’re trying to make these machines laugh and cry.

MD: Does the drummer have a unique role?

Mike: This whole hierarchy of drummers being “backup musicians”…there’s been this kind of conventional wisdom, “He’s just some idiot backup guy.” To me, everybody involved goes into the whole deal. Nature favors some frequencies over others in some ways, but to make a full sound you need all the parts. Advertisement

Actually, we’re all drummers. I’m working those strings with my right hand, and I’m kind of playing a little drum part. The rhythm is involved with everything. The drums are the great rhythmic ancestor. I don’t know how it came about, maybe it was ancient people dancing, and their feet pounding the ground acted as the first drum.

MD: You said that in a way all instrumentalists are drummers. But we’ve all heard some musicians say things like, “The drummer is responsible for the time, and everyone is leaning on you.” Others feel that everybody is responsible for the time, that it shouldn’t just be the drummer’s job.

Mike: And you know what, sometimes it works if the drummer ain’t got such good time, like with the Who. John Entwistle on bass had this incredible time, and that kind of freed up Keith Moon to just let the freak flag fly. I don’t think the guy ever used a hi-hat until the later stuff. And you needed that, it was kinetic. So whatever the situation calls for…. The whole idea of roles, this is kind of what attracted me to the punk thing. These people didn’t even know how to play, which threw things out of kilter in terms of the role-playing, the hierarchies. Bass was traditionally the place you put the lame guys. But all of a sudden when you had all lame guys, Bass Guy got all equal. Advertisement

A journalist once interviewed John Coltrane and asked him, “What are you listening to when you’re soloing”? He said, “I’m listening to the bass.” That was such a great thing to hear. Now, yeah, acoustically we do have kind of a narrow part of the sound, and as far as the drummer goes, I have to admit that I listen to the kick drum first, because that’s the note I share.

MD: In the Minutemen you all seemed to really enjoy creating an unending variety of musical worlds. It was as if you would agree on a certain direction, a certain feel or whatever, and then do whatever was needed to make that thing happen. There was very little sense of, “This is where the B section has to go like this….”

Mike: Yeah, you hit on it. Boon once said, “What we are doing is almost economics. We are building a little economy here.” We do certain things to put it together, and we tried not to relegate so much, because it can be dynamic and change in the moment. [Visual artist] Raymond Pettibon and I were eating dinner with [pioneering punk musician] Richard Hell last week, and he said, “When you first make a band, there’s all these possibilities. And then sure enough, because of the bad habits we have as humans, we start narrowing it all down.” All of a sudden all those things that were possible become, “Oh, this is the way we do it, this is our sound, this is our image…” and you end up doing I Love Lucy reruns. But you started at this point where anything was possible, at a time when you probably didn’t know as much. Isn’t that trippy how knowing more actually might hurt? Advertisement

MD: That seems to be the thing about so many of the bands that came out of that punk era: Because of their limitations, they were forced to kind of come up with some other ways to do something interesting or catchy.

Mike: Yeah, and that’s what really attracted us. In fact, we didn’t even think it was a style of music, it was just a way of doing things by letting it all go. Reassessing everything and creating with what’s at hand, and not having any preconceptions keeping you constipated in the head.

MD: Back to improvising for a moment. We can agree that it’s all about listening and not treating music as a hierarchy. But what about the literal work of listening as you are concentrating on playing? Is it a matter of doing it until it becomes second-nature, or is it some kind of an independence skill that you can perfect? It seems to be a hard thing for people to do. Advertisement

Mike: Yeah, and technique absorbs so much of your thought, it’s easy to miss the big picture. That’s probably why orchestras have conductors, even though you’ve got these amazing technicians. I saw this happen once. You could tell it was kind of all over the place—and these were first-class musicians—but the conductor got them to submit, not in a mean way, but he just got them to give up a little bit. And the thing got so powerful. I heard it right there, just like the way a garage band comes together.

Somebody told me once that the mind can only focus on three things at a time. So a lot of credit goes to the drummer. He’s got his whole body moving. He’s the most multi-task guy of us all—kick, hi-hat, snare, toms…he’s got to keep that all together. So obviously for him, it’s the groove, it’s the rhythm. Also the tones of his instrument aren’t as pronounced as maybe the melodic instruments, so he’s thinking more about the groove. But then I’ve read about Coltrane and why he like Rashied Ali, who played with no time. Coltrane wanted to get away from time. He wanted event-driven things instead of time-based things, which is an interesting way to look at it…a lot more drama, a lot more “film” or something.

MD: You’ve played on and off with George Hurley for quite a long time. Have you seen your playing relationship change or morph, or is it the kind of thing where you played together so much early on that you’re not really thinking consciously about it at this point? Advertisement

Mike: Things develop from playing with somebody, big time. It’s kind of an invisible thread between you, because you have shared so much time together. And there’s the give-and-take thing. Sometimes it’s like, Maybe I can inspire him with this lick here, or by leaving these openings here. Or you might think, That’s kind of interesting what he’s doing, I’m going to follow his lead. So there’s not a lot of contention, like who’s the cart and who’s the ox. And you get confidence from that familiarity, like, He’ll catch me if I fall. He knows I’m not trying to cut him. We’ve been doing this awhile, so, okay, the loop comes up a little short this time—that’s alright, he’ll be there for me on the 1.

MD: Given what you were talking about before regarding the open-ended nature of early punk, what was George’s musical role at the beginning?

Mike: Punk was, first, an opportunity. Instead of just copying, let’s see what we’ve got, what our inside voice sounds like. So there is always a gratitude towards that, almost a debt we felt. Also, being a power trio and wanting to make an interesting conversation out of the format, we really worked on the songs. We still wanted a beginning, middle, and end, and we would work out all the parts so that the drums could come in and have little things too. We didn’t want the drummer just to be a backbeat, so we’d have Georgie come in and work out a lot of fills and stuff so they’d be very conversational too. And so there’s a camaraderie there—leaning on each other to make the whole, knowing that if one cat fell the whole thing would fall. Of course D. Boon and I had a personal thing, since we were buddies before the band, and this was one way we were friends, how we shared the music. Then we kind of brought that to Georgie too.

MD: You’ve got pictures of D. Boon and John Coltrane on your bass. If there were room for a picture of a drummer, who might be there?

Mike: Oh, man, I really like Keith Moon. We all did. There was something about him. He was an enabler. It’s funny, if you’ve ever heard Pete Townshend’s demos and then what the songs sounded like when Moon’s brought aboard, how it changed. Advertisement

Then there’s Dave Grohl…one of the most blow-away players. I know he doesn’t like to play drums much nowadays, but man he was something else. George Hurley, of course. There was a band from the late ’70s called the Pop Group, and their drummer, Bruce Smith, was incredible. They were kind of the band Gang of Four copied—this idea of taking Beefheart and mixing it with Parliament. Smith was only eighteen or nineteen years old, but I guess he was listening to all kinds of things. He had a big affect on us, and we never even got to see him. We only knew him by the records.

Of course there’s Benny Benjamin and the Motown crew. Then there’s a cat like Elvin Jones. Have you ever seen that video, A Different Drummer? He talks about how the drums are colors, and how he’s painting when he plays—what an analogy. But Elvin had a lot of trouble when he started. Guys said, “Hey, you’re not playing the time.” There was a lot of controversy.

MD: You haven’t lost your passion or your interest in new music and discovering stuff. How are you feeling about music these days?

Mike: There’s a mixture. If you think back, Pat Boone sold more “Tutti Frutti”s than Little Richard. That was fifty years ago. But any farmer would tell you, if you want a good crop, use a lot of manure. So bring it on. You can be a little more cynical because the marketing has gotten more savvy, but I wouldn’t want to put any nails in the coffin. Also, technology has got more econo, so you’ve got more cats in the game. You can make music in bedroom studios no problem. That was something that you couldn’t do in the old days. So the opportunities may be more, though the burden of being creative will always be there, which maybe isn’t a bad thing. Advertisement

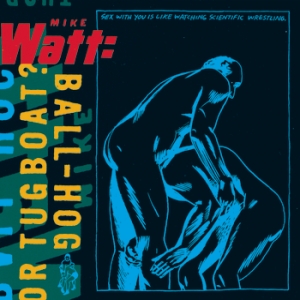

Ball-Hog or Tugboat: Mike Watt’s Alternative All-Star Drumming Goldmine

Mike Watt’s major-label solo debut remains a wonderful oddity of modern music. Populated by members of Sonic Youth, Pearl Jam, the Lemonheads, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Jane’s Addiction, Nirvana, the Meat Puppets, and Dinosaur Jr., among other alternative-rock institutions, the album unsurprisingly features some awesome and varied drumming. Lead-off track “Big Train” kicks things off with a heavy push worthy of its title, dominated by a typically swashbuckling Dave Grohl performance. Elsewhere, Nels Cline’s Michael Preussner takes a skittery, prodding approach, nudging several tracks toward their prescribed end points. And sax-y workout “E-Ticket Ride” got some airplay thanks in no small part to the split drumming duties of Jane’s Addiction’s Stephen Perkins and Bruce Hornsby’s John Molo. Other tracks feature the work of Bob Lee (Clawhammer), J. Mascis (Dinosaur Jr.), Brock Avery (Wayne Kramer), Richie West (Camper Van Beethoven), and Steve Shelley (Sonic Youth), helping make this a must-have for indie rock–drumming fans. Wax junkies need to track down the blue-vinyl version for maximum effect.

This interview originally ran in the December 2006 issue of Modern Drummer magazine. To order a print copy of that issue, go here.