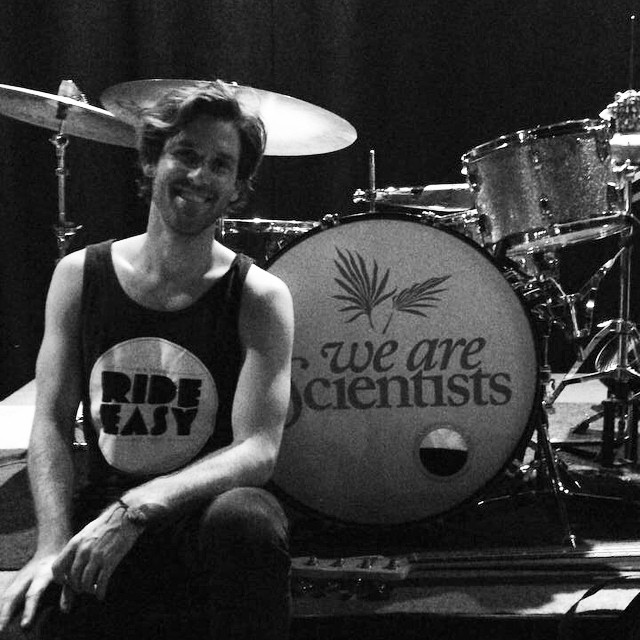

Keith Carne on We Are Scientists’ <i>Helter Seltzer</i>

by Adam Budofsky

Brooklyn-based indie-rock band We Are Scientists’ fifth album, Helter Seltzer, released digitally this past April 22 and physically on June 3, is an advanced-level course in hook-ology. Vocal choruses, guitar lines, keyboard figures, and, yes, drum beats and fills share equally in the job of keeping the ear-worm factor a top priority. Keith Carne, a busy New York City drummer whose varied gigs and background in journalism contribute to his easy understanding of the “bigger picture” concept, inherently gets what’s needed here, namely well-sculpted rhythmic support, thoughtfully placed commentary, and metric and emotional strength. Modern Drummer wanted to learn more about the experiences and attitudes that inform Carne’s approach with the popular and inventive band.

MD: The drum sounds on Helter Seltzer are huge. Please tell us a bit about the approach to recording—where and when it was done, and whether there was any discussion ahead of time as far as what kind of vibe you were going for.

Keith: The album’s producer, Max Hart, is one of the most well-prepared musicians I’ve ever met, so the record was built around a pretty exhaustive pre-production process. All of the songs started as rough demos that our singer and guitarist, Keith Murray, put together. Many of those demos had simple drum parts that Keith—again, Keith Murray, lest you think I have some sort of third-person-George-Costanza complex—plunked out on a MIDI controller, mostly just to give the rest of us an idea of the way he wanted the songs to feel. Max and I took those demos and mapped out the underlying beat structure, when and where we wanted any sorts of feel or texture changes—double or half time, or switching from the ride patterns between textures—and places where we needed composed, fully orchestrated fills. We recorded those interpretations using real drums at a pre-production studio in the Dumbo section of Brooklyn. After making some final tweaks to the “final demo” parts, we set up shop at Downtown Studios in Lower Manhattan, and that’s where the drums you hear on the record were recorded. Advertisement

This was great way of working, because Max and I had already developed a dialogue about the way the drums should be tuned, and we were prepared to evaluate what was good about certain takes and what didn’t work about others. There was also the added benefit of efficiency; because we went in knowing exactly what we were looking for, I was able to record all of the final drum tracks for the record in only two days.

MD: The cymbal sounds on the album are also very prominent and bold. Do you have any preferences in terms of sizes and weights in the studio versus live?

Keith: One could make the argument that with We Are Scientists, the kick, snare, and hats are the most important components of the drum setup, but I always tend to prioritize the search for the right cymbal sound with each of the bands I work with. Having the right cymbals makes me feel at home behind any kit. Usually I dig ’em big! It’s rare for me to use crashes. That said, one of my most trusted recording cymbals is a 19″ Zildjian K Dark Thin crash, and that thing is on a bunch of the songs on Helter Seltzer.

I pretty much stick to sweet-sounding rides that don’t sound too bronzey when you crash them. My cymbal setup changes all the time, but right now I’m totally hooked on a 24″ K Light ride for both studio and live applications. The stick definition is nice and clear, and the wash is somehow both trashy and sweet. I also leaned pretty heavily on a 22″ K Custom Dark ride, used as a crash, and a 20″ K Constantinople Thin ride with a tiny crack in the middle that gives it a wonderful complexity. Advertisement

Sizzle cymbals are where I run into the most difficulty live versus studio. Live, I love the way that rivets provide warmth, depth, and texture without adding volume. Live I use a ’70s A with four rivets and some paper clips on a key-ring for extra sizzle, or a 20″ notched Istanbul with two rivets—it’s signed Mehmet Agop, so I’m not sure which company it’s from. I’ve yet to figure out a way to get sizzle cymbals to sound as nice in the studio, though. I find that they’re a bit too rich and the sustain bleeds too much into the drum sound. Especially when recording digitally, I just find that the riveted cymbals make the kit sound like it belongs on a contemporary jazz record.

MD: What gear do you favor live and in the studio?

Keith: My go-to setup in the studio is built around a 1968 Ludwig orange-sparkle 14×22 kick drum. I also use the matching 8×12 rack tom. The previous owner didn’t keep it in the best condition. For some reason he painted the insides of the shells white, and they’ve been stapled and re-wrapped to hell, but they just sound so killer that it doesn’t even matter. In fact, their condition makes me feel less bad about keeping them in my closet in my apartment!

As for snares, one of my favorites is a 6×14 Allegra with 2″ wood hoops. Dana LaMarca, who served as the drum tech during the Helter Seltzer sessions, brought in his ’52 Leedy, which was just a total beef storm, and that beautiful drum is on a number of tracks. I think there’s also a Black Beauty in the mix as well. At the end of the day, though, I compare all of those highly specific drums to my 6.5×14 Supraphonic, which is maybe my favorite all-purpose snare. I usually use that live. Advertisement

As for drums on the road, I’m a bit wary of slinging a vintage kit around, so I often use a Ludwig reissue kit from the early 2000s. It’s a 14×24 kick and a 16×16 floor tom. I pair that with my ’68 rack tom. They sound incredible together, and I really dig it when pieces of a kit don’t necessarily match—the orange vintage drums look rad with the reissue kick and floor tom, which are green sparkle. Sort of reminds me of those sour patch kid watermelon gummies. [laughs]

MD: Lead-off track “Buckle” starts with a cool little drum fill that neatly forecasts the rhythmic feel of the song. How much do you consciously think about that sort of thing?

Keith: I’m a sucker for a rhythm hook that kicks off a tune. Especially if you can make reference to it later in the song, because then it becomes a theme, and that adds even more specificity and tightness to an arrangement. That specific drum fill was something that we thought through and composed. We knew that there should be a thematic, composed fill that appears throughout the song, and that one came after a couple of minutes of trying to beatbox it in the control room. A lot of the grooves and fills came about that way, actually—Keith or Max would sing a fill or a groove they wanted to hear, and my job was to basically interpret their booms and bops on the tubs.

I like to think of certain fills as touchstones in an arrangement, and Keith, Max, and I would play through demos and try to figure out where exactly those specific, composed fills needed to be. I’d make note of those and then improvise a lot of the other fills around the composed ones. I think it’s important to capture both composed and thoroughly considered fills, as well as off-the-cuff, improvised responses and setups on any recording. It sets up an interesting call-and-response dynamic. Advertisement

MD: I like the way you move the ride pattern on “In My Head” from the rim click to the hi-hat. What prompts a decision like that for you?

Keith: Thanks. I’m constantly thinking about theme and variation, and I’m fascinated by the way that changing the texture on a drumkit changes a song’s frame. Think about how different a verse sounds when you’re riding 8th notes on the floor tom instead of the hi-hat: it’s often warmer and more open, and yet it’s played over the same chord changes and likely supports the same top line.

Keith: Thanks. I’m constantly thinking about theme and variation, and I’m fascinated by the way that changing the texture on a drumkit changes a song’s frame. Think about how different a verse sounds when you’re riding 8th notes on the floor tom instead of the hi-hat: it’s often warmer and more open, and yet it’s played over the same chord changes and likely supports the same top line.

Keith M. used a rim click for “In My Head” on his original demo, and Max and I stuck with it because we hadn’t explored that texture yet on any grooves for the record. Also the great part about playing a ride pattern on a rim is that moving it to the hi-hat—the thing that’s often a drummer’s default—becomes a variation, and so that makes the typical kick/snare/hat combo suddenly sound fresh. The hi-hat itself is also a rich and complex texture, so moving it there also allows you to create even more variations within the groove by exploring sustain and punctuation with your left foot—getting some “air in it,” as Bernard Purdie would say.

MD: It sounds like there are some drumming overdubs on that part too. Did you do much of that on the record?

Keith: Yeah, there are definitely dubs on the record. Some are straight-forward like the ones on “Hold On,” which are just percussive elements like shakers and Roto-Toms. Or on a track like “In My Head,” we dubbed the rim-click triplets because we liked the clicks best on a wood-hooped snare, but we wanted a metal snare sound for the backbeats. Advertisement

One of the more interesting studio experiments we tried was breaking up parts between drums and cymbals. Basically I’d just lay down kick, snare, and toms and then we’d immediately overdub cymbal elements like sloshy hi-hats, crashes, and ride patterns on separate tracks. This allowed us to explore a ton of options for EQ’ing the drums, and even though I think we mostly wound up using takes where I played the drums and cymbals at the same time, it was an interesting way of working. I also understand a lot more pop records are made this way now because it makes blending acoustic drum sounds with samples that much easier, and the sounds that result are often huge.

In addition to the overdubs, there are also some really cool blended samples and programmed beats, which Max Hart put together.

MD: It’s cool how you drop out the snare on that last line before the choruses on “Too Late,” while the ride pattern remains. It’s an effective arrangement idea. I think it stands out even more due to the double hits on the snare throughout the rest of the song. Then when you go to the hi-hat opening on the upbeats, it adds another nice variation. Do you have favorite drummers to listen to in terms of how they approach variations to main beats?

Keith: Well, I don’t know if it gets much better than Ringo for simple theme-and-variation playing. I love the way that he strips the hi-hat away in verses and then reintroduces it in the chorus. It allows the song to feel so much bigger, yet it never feels cluttered, and you can make it even bigger again by going to the ride or the toms after introducing the hi-hat. I feel like that happens a lot on Rubber Soul and Revolver. Glenn Kotche from Wilco does this really seamlessly too. Jim Keltner…Levon Helm—think the chorus of “The Weight,” when the drums totally drop out…James Gadson—the way that he takes the backbeat out of every fourth measure and replaces it with upbeat hi-hat hits on “Use Me”…Joey Waronker on the Beck record Sea Change will often swap out a snare hit for a really reverby tambourine, and that introduces a nice suspension across the barline, like you’re waiting for the other shoe to drop. Advertisement

I always try to figure out the point where I want a song to feel biggest, and from there strip textures away in all of the sections that lead up to that point. It’s a great way to keep your playing tasty, and most importantly, stay out of the way of the song.

MD: How do you approach going from your recorded drum sounds to live? Do you use any sampling? The percussion sounds during the breakdown of “Classic Love,” for instance, are not typical drumset tones.

Keith: I use a Roland SPD SX live to cover sampled drum textures and partly to cover drones, noise, and shorter, melodic keyboard parts. “Classic Love” is a perfect example of a song that I use the sampler in all those capacities. I have a sampled 808 kick drum, hand-claps, an electric tom, and a drop on some of the pads, and I use those the way any drummer might, as digital supplements to an acoustic kit. Advertisement

I also have a pad dedicated to feedback noise that Keith M. recorded on his guitar—triggering that in the second verse introduces an interesting new texture. Four other pads on that saved kit are dedicated to reverby keyboard tones an octave above the guitar lead line. I’ll use those keyboard notes to support the melody that Keith plays on the guitar, with each note saved on a different pad. We play as a power trio live—guitar, bass, and drums—so it’s a great way of to add some variation to the melodic lines and to also impart some of that hollow synth space to the live mix. And because I’m not playing anything on the hi-hat on the part where I’m covering the keys parts, my right hand is free to trigger those pads. I try to cover as many keyboard parts as I can live, but we also don’t want to use tracks, because that makes the set too rigid from night to night. Keith and [bassist/co-leader] Chris Cain like to pace the shows differently, largely based on the way that a crowd is feeling, so that means my samples can’t be strictly time-based or dependent on a metronome.

MD: Can you talk a little about your background, like where and when you were born and raised, and what kind of early training you’ve had?

Keith: I was born and raised in Sayreville, New Jersey—exit 124 on the Parkway, so it’s in central Jersey—and I’ve been playing with the intent of becoming a better drummer since I was seven. I have two super supportive parents that got me a kit when I was three years old, and they encouraged creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, but also a strongly rooted practice regimen. For the first few years I just played along to tracks by ’90s alt bands like Stone Temple Pilots, Foo Fighters, Soundgarden, and Nirvana, but eventually my parents started taking me in for lessons so that somebody could fill in the pedagogical gaps, like technique and reading.

I went on playing and taking lessons until I was accepted at Rutgers University’s music conservatory, where I studied with Victor Lewis for four years. That was an incredible experience, but it would have meant little if I wasn’t actively involved in New Brunswick, New Jersey’s basement indie-rock scene. That’s when I started touring the DIY basement and indie-rock scenes across the country, and ultimately, what led me to meet most of the people I’m currently making music with. Advertisement

MD: You studied music and journalism at Rutgers. How have those two worlds co-existed since graduation, and does one discipline inform the other?

Keith: There are a ton of elements that factor into good writing, but usually it’s direct, focused, clear, and capable of knocking you on your ass at just the right times. Good writers know who they’re writing for too, and when a reader gets a whiff that a writer is trying to do too much, it’s usually a turn-off. I believe you can say the same thing about playing an instrument. It’s why people often say that two musicians playing together sounds like a dialogue, or why notes are grouped into “phrases.” Learning how to write a lede—the first sentence in news story—was hugely beneficial to my learning how to comp behind a soloist. It made me ask myself, “What am I trying to say here”? or “What’s the best way of setting that stage for someone else to say something”? And in asking those sorts of questions I cut out a lot of the fluff in my playing.

Since I’ve graduated I’ve worked in both radio and print media, writing music reviews or interviewing musicians, and obviously I’m able to draw on my own experiences as a practitioner when putting that stuff together. It’s mostly been helpful, though, because studying journalism is studying communication, and it’s as important to be able to have a conversation with a fellow player as it is to be able to make music with them. I began studying journalism in college because most people told me I was nuts for pursuing a degree in jazz music performance, yet in my years after college, ironically it was music that kept me living; I worked free internships for media organizations and was only able to survive by taking gigs and teaching drum lessons.

MD: What was your experience like working on The Leonard Lopate Show at National Public Radio?

Keith: I started out as a total NPR fanboy, in awe of this endless well of knowledge and trivia that hosts seem to be able to constantly draw from. Going to the station every day was a total trip. And everywhere you turn there are books, cool old microphones, CDs, posters—it’s a very inspiring place to work. Leonard Lopate knows so much about so many disciplines, and of course, the act of hosting a salon-style magazine show itself only adds to his wealth of his knowledge. No individual could possibly digest the amount of material required to produce ten hours of original programming a week—there are four interviews per show and five shows a week, so there has to be a dedicated staff of producers and interns to help Leonard review and digest the books, articles, films, plays, or whatever. Then together, Leonard and whichever producer was working that certain segment formulate questions and interesting points. The thing that totally blows me away is that regardless of the subject matter Leonard pretty much always seems to have some kind of personal connection to it, and often an intelligent and well-formed opinion about it. Mostly what you hear on the show, though, is the force of his personality—he’s just so easy to talk with, and it would even sometimes get me into trouble! We’d often wind up derailing our prep meetings and rap with each other about jazz music—he’s seen pretty much everybody and knows a ton about it. Advertisement

MD: You mentioned to me earlier that in your teaching practice you meet more and more players who are interested in a multi-faceted musical career. Please talk a little about how you have worked toward that kind of diversity in your own career, and what kind of barriers are typically in the way of that sort of goal.

MD: You mentioned to me earlier that in your teaching practice you meet more and more players who are interested in a multi-faceted musical career. Please talk a little about how you have worked toward that kind of diversity in your own career, and what kind of barriers are typically in the way of that sort of goal.

Keith: My goal is to be able to play any style of music and do so with expression and restraint. Financial reality in today’s music marketplace demands it. I’m convinced “formal” training in college is the reason I’m able to play a number of different styles well. Studying jazz performance is a bit like going to a musician’s boot camp. One could argue that jazz music has more moving pieces than most other music styles, and in studying it you’re mostly just preparing yourself to be a responsive and attentive player. Learning those skills is what allows you to adapt to any musical scenario.

Of course, you also have to listen to the music styles you’re trying to play so that you’re aware of conventions, norms, and most importantly, what not to do. I love playing country-swing music, for example, and playing in my country-swing band makes me combine my methods of approach for both jazz and rock. But it’s important to know that it’s just not going to sound right if you’re putting triplets everywhere like Elvin Jones. I think that kind of polyglot playing, with feet in two worlds, is one of the things that keeps me working. Advertisement

Ironically, the marketplace also seems to be as much of a catalyst as it is a barrier to one’s development. I feel most of my work connections come about because I live in New York City—it’s just tougher to meet bands capable of paying you to play with them when you live in the suburbs or in more isolated area. And New York is not cheap, so I necessarily have to dip into my practice time to work gigs to afford to stay here, sometimes even gigs outside of music. It’s an endless Catch-22, but luckily I can’t really imagine a more inspiring place to live.

MD: Can you talk more about your instructional work at Manhattan Drum Studios? For instance, what kind of students do you have, and what areas do you stress in your lessons?

Keith: My students run the gamut from five-year-olds to sixty-five-year-olds. New York City is an incredibly diverse place, and the student base at Manhattan Drum Studios is no different. Some attend the LaGuardia Performing arts high school for instrumental music, some play in cover bands, some are drummers working on the scene today, and some are just players looking to make as much noise as they can after being pent up in an office all day. That’s why, regardless of the student, I constantly encourage song-based education. I use songs as benchmarks, and each tune represents an intensive workshop on any number of concepts. For example, “In Bloom” by Nirvana is something I might bring to a student that’s looking to incorporate fills into their grooves, and in the process, we’ll also explore playing flams around the kit. I’ll use that Robyn tune “Dancing on my Own” to explore 16th-note hi-hat groove. I find that keeping lessons constantly focused on creating music, along with supportive fundamental work—like exercises from Syncopation, or the Rudimental Ritual—provides students with jam-packed lessons that are fun, meaningful—even cathartic.

MD: What are some of the other artists that you play with besides We Are Scientists, and what are some of the specific demands of those gigs?

Keith: I have the privilege of playing in a number of really great projects with bands in New York. My passion project is a band called Brian Bond and the Communipaw, an indie-rock band that I’ve been writing, arranging, and performing with for almost ten years now. I support a bunch of singers and songwriters from all over, including my good friend PJ Bond. I also play with an improv-oriented folk band called Power Mystery. That band features an interesting mix of instruments, and my setup comprises a snare drum, cowbells, bells, blocks, and some Le Creuset cast-iron pans. My buddy Jeff Widner also plays drums in that band, and he uses a kick and toms, so it’s basically like we’ve split the kit between the two of us. He and I have to listen to each other so that we can sound like one drummer. That in itself demands that I play quietly enough to hear what Jeff and the other band members are playing. Advertisement

Regardless of the project, playing expressively at low dynamic levels is something I’m always thinking about. New York City is obviously a cramped place, so it’s not uncommon for venues, rehearsal spaces, apartments—wherever you’re hitting—to be less than ideal acoustically. You can combat that big variable by learning to play quietly. The ability to know how to wrangle a house kit is also extremely helpful when I’m playing with these other bands, as it’s neither encouraged nor desirable to bring your own drums to small New York City venues.

MD: What are your personal and professional goals? Do you hope to make them happen in the New York area, or do you have plans to see what else is out there in other parts of the world?

Keith: In the short term I’d love to work more jobs playing jazz and improvised music. Most professional freelancers will usually tell you that they have an incredible amount of guilt when they’re not working on something that will support their craft. I’m lucky enough to always feel that guilt at my heels, and that’s what keeps me practicing, learning, and working on all of my problem areas. It’s really important for me to keep learning and exploring and to keep my ears open. Also to share all of the things that I learn from and about playing with interested and motivated students.

Exploring new cities would be great, but the reality of most freelancers’ existences is that gigs are based where you are based, so by moving someplace else, you often forfeit the things you worked so hard to establish. Luckily my job keeps me traveling, and after this album cycle is through I plan to visit Brian Bond in India’s Gujarati desert to study with a few drummers in that region. I’ve been to India before to study tabla, and that was a game changer for me. Mostly, though, I’m just excited about all the options for playing that lie ahead. Advertisement

To stay current on all of Modern Drummer’s multimedia postings, including features like this one, sign up for MD’s monthly newsletter, The Wire, right here.