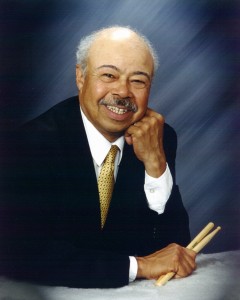

Count Basie/Tony Bennett Drummer Harold Jones

by Robert Girouard

Harold Jones is a marvel. While some people his age are already living in retirement homes, the seventy-five-year-old drummer is busy globe-hopping with another over-achieving American musical icon, Tony Bennett.

Jones began his career in the early ’60s with saxophonist Paul Winter, which led to his big break, with jazz icon Count Basie. A two-week stint as a fill-in drummer turned into a permanent gig, touring the world with Basie and cutting more than a dozen albums. In 1972 Jones was recognized for his achievements with a win in the Downbeat International Jazz Critics poll for best new artist.

Jones was later asked to join legendary jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald’s band. Around that time he also began working with singers Nancy Wilson, Carmen McCrae, Tony Bennett, and Sammy Davis Jr. In 1980, Harold joined jazz vocalist Sarah Vaughn, with whom he toured the world, including playing the White House on five separate occasions. In 1990 he joined forces with Natalie Cole, playing on her hit album Unforgettable and its supporting tour. Advertisement

In 2001, as a staffer with the Henry Mancini Institute at UCLA, Harold played with Quincy Jones and Robbie Williams. In addition to teaching at colleges and universities, he led a seventeen-piece big band. In 2004 he permanently hooked up with Tony Bennett, and he spent the first half of this year out on Bennett’s Cheek to Cheek Tour, featuring Lady Gaga.

Watching a show featuring Jones on drums is like receiving a lesson in form and finesse from a living legend, which he unquestionably is. Earlier this year Harold sat down for a chat with Modern Drummer just prior to hitting the stage at New York’s Radio City Music Hall with Bennett and Gaga.

MD: Your parents were very influential in your life, nurturing your musical dreams. How did music-making begin for you?

Harold: When I was growing up in Richmond, Indiana, my mom put me in summer music camp: Fourteen weeks, five days a week, for fourteen dollars! I wasn’t happy at the time because I was trying to play sandlot baseball. I wanted to be a pitcher, but I missed so many practices that they stuck me out in right field. Advertisement

Musically speaking, I had very good teachers. A guy named Don Sherman recommended Jack Kerkowski. He had a xylophone band that played in all the Vaudeville shows. Back then the bass drum was like 30″, and we played stick beats on it. I also learned the rudiments, and they were not only my Bible but a kind of dictionary to refer to. Another drummer who really helped me was Joe Hunt, who taught me about guys like Max Roach and Charlie Parker.

MD: You’ve said more than once that your five years with Count Basie [1967-72] were the greatest in your career. What about being in that band made it so memorable?

Harold: All the great singers wanted to have Basie back them. So I got to work with singers I never would have met, like Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, Tony Bennett…you name it.

MD: There were some heavy cats in that band, “lifers” like Freddie Green and Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, and Harry “Sweets” Edison. They must have kept a youngster like you on your toes. Graduates from the Basie band often refer to it as “going to school.”

Harold: Absolutely. And that’s why I say that nowadays younger musicians don’t have the “universities” of the big bands like we did coming up. Basie, Ellington, Herman, Kenton, Ferguson, Rich, etc.—they served as the training grounds on the road. And school music budgets slashed all the time, which is why Tony Bennett puts his time and money into his own school, the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts. http://franksinatraschoolofthearts.org Advertisement

MD: Big Band swing is a highly specialized craft, while some say it’s an art form in decline. There are only a few drummers left, such as yourself, Butch Miles, and Peter Erskine, who qualify as masters in that department. Considering the excitement it brings, why do you think it’s largely been relegated to regional pick-up bands?

Harold: The bottom line is that it’s too expensive to take a large ensemble out on the road. And I can’t understand it, because it’s great music, and the budget is no more than a promoter would pay for some “in the moment” rock act.

MD: There’s some killer stuff out on Youtube with you and Basie. One example is “The Magic Flea,” where you burn from start to finish. You’re like Muhammad Ali on that cut—you’re floating over the drums. Advertisement

Harold: When I joined the band, the first recording I did was written and arranged by Sammy Nestico. I mean, we’d go in the studio, sight-read it, and record it! When I came along, Sammy was my favorite. We both arrived at the right time. He knew how to write a drum chart: leaving it open for me to interpret, and putting the horn figures in so I could do what I want with the figures.

MD: You’ve seen the music business from every angle. At seventy-five, you’re playing a sold-out show at Radio City. It has to be so special for you.

Harold: It feels good. But it feels good because you know that you did your homework. I also think it comes down to having respect for people like the guy who’s picking up the trash in the theater after the show, as well as the CEO sitting in the front row.