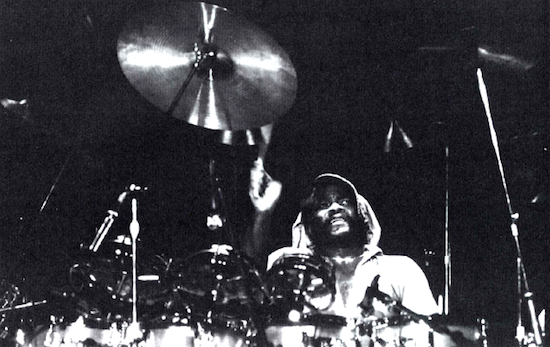

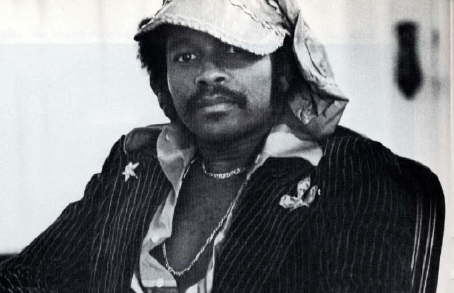

Alphonse Mouzon Passes

At the time that this story was originally posted, legendary fusion drummer Alphonse Mouzon was appealing to fans to help fund treatments for his battle with a rare form of cancer, neuroendocrine carcinoma. Mouzon lost his battle with the disease on Sunday, December 26.

Alphonse Mouzon came to prominence in the ’70s as one of the top drummers on the burgeoning fusion scene, playing with premier acts like Weather Report and Larry Coryell’s Eleventh House. A greatly respected player, Mouzon was admired by no less than Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham, as recounted by singer Robert Plant in his speech at the band’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1995.

The following interview with Mouzon originally ran in the March/April 1979 issue of Modern Drummer. At the time of this interview, he was working with Herbie Hancock, was fronting his own group, and had recently released an album as leader, In Search of a Dream. Advertisement

MD: Which of your past musical experiences do you feel you have learned the most from?

AM: I learned more musically with McCoy Tyner than Weather Report. For other things I listened to everybody, and learned from them. Things I listen to now include Top 10, Top 40, all R&B, and rock ’n’ roll. Because my mind is open, I don’t want to always be identified as just a jazz drummer. I got my start through jazz, and I’m not putting it down. But there are other things I do.

MD: Do you have a warm-up procedure before you do a concert?

AM: I used to, but I don’t find it necessary now. When I was playing opposite Billy Cobham with Larry Coryell, I could see him in the back with a pad, doing his chops. I’d walk around drinking champagne or something. I might twist a wrist with the sticks or stretch before I go on, but that’s about it. If after all these years your wrists aren’t developed, then you don’t have it. If you’re not warmed up in the first song then you’re not going to get it.

MD: Let’s talk about the matched grip versus the traditional.

AM: Sometimes I use both. When I’m doing light things or jazz things or swing things, I might use the conventional, but I like to feel primitive many times, so I use the matched grip.

MD: Do you find yourself using that more?

AM: Yes, because that’s the way I started out when I was a baby. I stopped when they told me it was wrong, but it felt unnatural to put it in my hand from the left side with the second finger. That all started because in a marching band the drums were slanted, so you had to play them that way. Advertisement

MD: How do you approach drum solos?

AM: It just happens naturally, so I don’t think about it. I don’t try to plan it out because then it’s not natural. I don’t think, Well I’ll start soft here and gradually get louder. If it happens that way, it happens.

MD: Can you describe your concept of the drummer’s role in a rhythm section?

AM: The drummer’s role is keeping the unit together and keeping the rhythm together. The energy level must always be there when it’s supposed to be. He’s the anchorman, holding everything down and giving energy and accepting energy. Receiving and giving. It’s boring if the other players don’t supply energy. When I play with bands and I’m giving the energy and don’t receive it, I can’t play anymore. It drains me if I’m with players who can’t play.

MD: Do you find audience feedback important to obtain that flow of energy?

AM: Yes. If I see one person in the audience involved, it will give me enough energy to channel back and put out. European audiences can be very passive; they look like they’re not enjoying themselves and yet they are into it because they’re serious. When they listen to classical music there’s no movement at all, no expression on the face, no twist of the lip or anything. But afterwards they show it by applause. They like what you’ve played so much that they want an encore. I’m always going through that. With this last tour people were jumping on the stage. I couldn’t believe it. This was a jazz audience and I was doing some funk things. I was trying to broaden my image. I was doing a jazz-rock thing and just broke out into a funky thing. Advertisement

MD: That type of audience doesn’t usually respond like that?

AM: No, but they did in Berlin. I played a half-hour encore because I got scared when somebody threatened us. They told the bass player, “If you don’t play, there’s gonna be a fight.”

MD: You play a lot in Europe. Where do you like to play the most?

AM: I play a lot in Germany. That’s where most of my audiences are. I also play Paris, Scandinavia…. I’m supposed to be going to Poland this year. I do mostly concerts and play at a few clubs.

MD: What’s it like for the touring drummer in Europe?

AM: It’s not that difficult. When I go over there I have a lot of one- nighters, and that can be the same in the States. I fly and travel by first-class train service. Their train system is much different from America. In little towns you don’t fly so you have to take a bus. And that way you get a chance to see Europe. The continent is beautiful. I have European roadies that take care of all the equipment on the one-nighters, so I just worry about getting to the hotel from date to date. It’s really no problem at all.

MD: What do you listen for in a drummer?

AM: It depends on the music. I listen for the creativity, ideas, concept, punctuation, articulation, feeling. If it’s a funk band or whatever I listen for the same things but also for the soul or funk in it. If it’s a bad group you don’t look for anything because you know there’s going to be a boring beat. If there’s any kind of creativity you’ll listen. If it’s in the music the drummer should be applying it to the music.

MD: Do you believe electric fusion music is declining in popularity, or will it evolve into something else?

AM: It is declining in popularity. But in Europe it’s different because European audiences like good music, whatever it is.

MD: They listen to it first and label it later?

AM: They’ll label it but they’ll listen to it. They’ll keep listening to it if it’s good. In the States, what’s winning is pop music, rock music, and R&B.

MD: Do you think disco is still strong?

AlAM: Yes. Disco in America is different from disco in Europe. For Europeans, when you say disco it’s a turn-off because disco is unfeeling music. It’s all programmed and played with no feeling. Disco is very hard to define. In America, disco could be funky too. I’ve heard some good music and I’ve heard some electronic disco music that was very boring. I’m into the more feeling disco music of the Tramps and Bee Gees. Some of the stuff from Europe is good and some is boring. The 4/4 on the bass drum, 2 and 4 on the snare, and 8th notes on the hi-hat is a very easy beat. I take that same beat but have everything funky underneath and music on top. And that’s where it’s important if you still have the rhythm underneath, and can play whatever you want on top.

Advertisement

AlAM: Yes. Disco in America is different from disco in Europe. For Europeans, when you say disco it’s a turn-off because disco is unfeeling music. It’s all programmed and played with no feeling. Disco is very hard to define. In America, disco could be funky too. I’ve heard some good music and I’ve heard some electronic disco music that was very boring. I’m into the more feeling disco music of the Tramps and Bee Gees. Some of the stuff from Europe is good and some is boring. The 4/4 on the bass drum, 2 and 4 on the snare, and 8th notes on the hi-hat is a very easy beat. I take that same beat but have everything funky underneath and music on top. And that’s where it’s important if you still have the rhythm underneath, and can play whatever you want on top.

Advertisement

MD: Do you still play brushes?

AM: Yes! I played them last November on tour, I had Miroslav Vitous with me, and Stu Goldberg, who plays keyboards on all my tours, and Bobby Malach, a saxophone player currently playing with Stanley Clarke’s band.

MD: Do you have anything recorded with you playing brushes?

AM: No, I don’t have anything on record. I started out playing brushes in cocktail groups with the Horace Parlan trio. I don’t play them as much anymore, but I still know how to play them. When I played them last year it felt good, stirring the soup.

MD: Do you hope to get back on the scene in the U.S. and tour sometime in the future?

AM: That’s why I’m working on it in Europe, just building my career over there. I’d like to join a super rock band that’s creative and sells too, somebody like Genesis or Yes. That’s something I would really like to do. I’d like to tour and have the big promotion and records and everything. Nobody knows that, they think I’m a jazz drummer and that’s all. They’re crazy. Advertisement

MD: You mean a lot of people think you play one way and that’s it?

AM: Yeah, yeah.

MD: But you can play in any context?

AM: Right, but I don’t get those calls because people are scared. That’s why I don’t do studio too. I did a record with Donald Byrd called Caricatures, and Sonny Edwards was the bass player. He used to play with Stevie Wonder. Edwards had a session and called the producer. He said, “I got Alphonse Mouzon, man, and we’re really hot together as a rhythm section.” The producer asked, “Isn’t he a jazz drummer?” Even though I play R&B, disco, and funk, he didn’t want to take a chance. That’s what happens. They say, “Oh he’s a jazz drummer,” and don’t call.

MD: So you’re typed just like film stars are typed?

AM: Right. I’m marked!

MD: Let’s talk about your equipment. Do you carry extra pieces of gear with you to allow for breakage?

AM: Yes, that’s why I have four snares, three extra hi-hat stands, six cymbal stands, and extra bass drum pedals.

MD: Do you break a lot of cymbals?

AM: Sometimes. I usually change them after a year. I have to be careful of those extra light crashes. I like their sound but if I hit them the wrong way they can give.

MD: Have you experimented with drum synthesizers?

AM: I haven’t performed on any live but I’ve gone into music stores and tried out several, like Syndrums and Synares. They’re nice but I wasn’t overwhelmed. I do have to figure out the drum synthesizer and how I want to use it for my music, so that it’s not mechanical and cold. Hollywood producers in the record industry always want something different, so they demand that everybody has them. Mostly session drummers have them. If you’re doing sessions and one guy has it, all the studio drummers must get it. If you don’t have it, they’ll call another drummer.